This guest blog comes from Lou Lefort, a third-year student of BA Social Sciences in the Education, Communication and Society Department (Faculty of Social Sciences and Public Policy).

In 2018, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned that the worst impacts of climate change could be irreversible by 2030. In 2021, the COP26 was designated as “the world’s best last chance to get runaway climate change under control”. A strengthening of the global response to the climate threat is urgently needed, by way of combined efforts towards sustainable development.

It is in this spirit that, in April 2020, the College of Mayor and Alderpersons approved the Amsterdam Circular 2020-2025 strategy. Despite the already steep fall of the world’s economies due to the start of the Covid-19 pandemic in March 2020, the City Council saw the situation as an opportunity for a more sustainable start.

The Amsterdam City Portrait

Towards a sustainable city

Today, the world’s urban population is estimated to be around 4.4 billion people (International Institute for Environment and Development, 2020), and is expected to keep increasing over the years. However, cities are not sustainable. As hubs of consumption, they are connected to supply chains all around the world and their food, transport and energy networks induce a massive ecological footprint.

It is through a circular economy strategy that Amsterdam strives to become sustainable and maintain an ecological balance. Circular economies seek high rates of recycling, refurbishment and reuse in order to reduce the use of new raw materials and avoid waste. The Amsterdam Circular Strategy was approved with the objective of halving its use of new raw materials by 2030 and achieving a fully circular city by 2050. Rather than an obstacle, the slowdown of all activity due to the COVID-19 pandemic, allowing a brief thrive in nature, was considered as an exceptional opportunity to introduce new politics. Working with the Dutch government and the European Union, the City of Amsterdam selected Kate Raworth’s Doughnuts Economics to implement and satisfy the demands of climate change and sustainability.

The Doughnut Economics

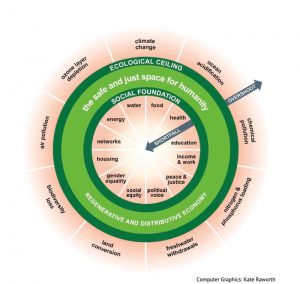

Firstly published in 2012, Doughnut Economics thrive for “meeting the means of all people within the means of the planet” (Raworth, 2012). The doughnut represents the “safe and just space for humanity” (Figure 1.). The inner ring is the social foundation, standing for life’s essentials that no one should fall short of, such as food, health, education or peace. The outer ring is the ecological ceiling of the planet. It constitutes the planetary boundaries not to overshoot to remain sustainable, such as air pollution, ocean acidification or ozone layer depletion.

The economist Kate Raworth vouches for a thriving economy, dismissing the contemporary imperative for endless growth. She rejects Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth as a measure of economic success and instead, advocates for this dashboard of indicators based on objective values and grounded in human and ecological flourishing. In practice, the Doughnut must be transformative to shift the long-term dominance of capitalist growth, through the enacting of new regulations and institutions embedded in nature. In addition, it must be regenerative by design. Biological materials need to be regenerated and technical materials restored, in order to close the cycles of use and avoid waste. Finally, the Doughnut in practice must also be distributive. Wealth, education and empowerment should be equally accessible to all and circulated by a bottom-up and peer-to-peer pooling of knowledge. The objective is to redistribute resources, power and control to decentralised networks in ways that address inequality while supporting innovation and representation in the fight against climate change.

In order to satisfy these demands in the context of Amsterdam, the Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL) created the Amsterdam City Portrait, in collaboration with Biomimicry 3.8, Circle Economy, and C40. Analysing the city life and its impact through four lenses – social, ecological, local and global – the portrait presents what it would mean for Amsterdam to thrive as a city. It essentially asks a 21st-century key question:

“How can Amsterdam be a home to thriving people, in a thriving place, while respecting the wellbeing of all people, and the health of the whole planet?”

(Amsterdam City Portrait, 2020, p.3)

The analysis is made through recent and relevant data from official sources to give a holistic snapshot of the current status of the city. The portrait is a result of a cross-departmental collaboration within the city, between its municipality, businesses and residents. It also required input from internal and external stakeholders, such as private and non-profit organisations. The application of Doughnut Economics relies on technological solutions to manage environmental risk, focusing on biomimicry in cities. The plan is to use scientific and technological knowledge to ‘work like nature’ and reproduce healthy local ecosystems. From the use of ‘bee-hotel bricks’ to the incorporation of green roofs, the City Doughnut provides a smoother and achievable transition from the capitalist economy while benefiting the planet, by scaling down ecologically destructive and unnecessary industries.

In order to keep track of the progress and determine the social and ecological impact of the transition, Amsterdam developed a monitor. It will identify the areas which need more work to reach their targets in time and ensure the city keeps its promise to become fully circular by 2050.

Application and challenges

The Doughnut Economics’ motto aiming to “meet the means of all people within the means of the planet” (Raworth, 2012) is an ambitious vision that cannot be fulfilled without active participation across the whole community. The DEAL and its collaborators stressed the importance of bringing together the city stakeholders to bring about change in a thriving manner. To ensure the participation of every willing Amsterdammer, they held workshops in seven diverse neighbourhoods to hear their vision and priorities concerning the city. Everyone is invited to participate and share their ideas, as the emphasis is put on the citizen-led aspect of the city’s transformation. The aim is to empower and connect the citizens while giving greater recognition to the existing community networks. Such collaboration between the residents, the businesses and the municipality enables the identification of common goals, making them co-authors of the Doughnut strategy. One of the Doughnut’s principles is to “nurture human nature” (Amsterdam City Portrait, 2020, p.18) by promoting diversity, collaboration and reciprocity. Such a mindset strengthens community networks and trust, helping to create social and ecological benefits. It can encourage citizens to consume locally, to exchange services, but also to respect each other, and hence, each other’s environment. As a result, the City Portrait was created by and for the people of Amsterdam, including them in each step of the process from decision-making to the sharing of tasks via community-based projects.

However, practical challenges can impede these ideas. Despite the City Doughnut aiming to always engage critically with power relations, the distribution of power can be limited. It is important to acknowledge who came to the Doughnut workshops, but also who did not, and why. Some citizens might not have been able to attend the workshops or to voice their concerns. Different actors present different types of knowledge, and some types of knowledge may be favoured. As a transformative practice, Doughnut Economics seek to enact new laws and regulations, and will consequently work more closely with the political actors. It is vital to keep the citizens in the loop and maintain the idea of distributive responsibility in the context of policymaking. For this purpose, it is crucial that the sources and methodologies to extract data on the city and its ecological footprint remain transparent and critical.

As a developed European capital, another practical challenge will concern Amsterdam’s choice of investment and imports, which can both hinder the social foundations as well as the planetary boundaries imposed by the Doughnut. The port was identified as a major practical issue, being the 4th busiest in Europe and the world’s single largest importer of cocoa beans (ibid. p.12). The labour conditions of cocoa workers are often exploitative, undermining their rights and well-being. The portrait remains optimistic and presents the many innovative companies that have been developed as alternatives, or the civic organisations committed to the defence of human rights.

To conclude, Amsterdam’s response to becoming more sustainable relies on Doughnut Economics which can be summarised as striving to ensure life’s essentials for all people, within the planetary boundaries. Following a transformative, redistributive and regenerative design, the city’s circular transformation seeks to be citizen-led, allowing Amsterdammers to be at the core of the process, from the decision-making to the implementation. Nonetheless, some practical issues remain and must be carefully monitored.

Overall, the adaptation of Doughnut Economics in Amsterdam represents real and hopeful progress for the development of sustainable cities and the fight against climate change.

References

C40 Knowledge Community. (2020). Amsterdam’s City Doughnut as a tool for meeting circular ambitions following COVID-19. [online] Available at: https://www.c40knowledgehub.org/s/article/Amsterdam-s-City-Doughnut-as-a-tool-for-meeting-circular-ambitions-following-COVID-19?language=en_US

Doughnut Economics Action Lab, Circle Economy, Biomimicry 3.8 and C40 Cities (2020). The Amsterdam City Doughnut. [online] Available at: https://www.kateraworth.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/20200406-AMS-portrait-EN-Single-page-web-420x210mm.pdf.

Gemeente Amsterdam (2015). Policy: Circular economy. [online] English site. Available at: https://www.amsterdam.nl/en/policy/sustainability/circular-economy/.

International Institute for Environment and Development. (2020). An urbanising world. [online] Available at: https://www.iied.org/urbanising-world#:~:text=The%20world’s%20urban%20population%20today,1900%20and%2034%25%20in%201960.

Raworth, K. (2012). A safe and just space for humanity. [online] Oxfam Discussion Paper. Available at: https://www-cdn.oxfam.org/s3fs-public/file_attachments/dp-a-safe-and-just-space-for-humanity-130212-en_5.pdf.

Raworth, K. (2018). Doughnut Economics: seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. London: Random House Business Books.

THE ALTERNATIVE UK. (2018). Are there holes in “doughnut economics”? Kate Raworth takes on a major critic. [online] Available at: https://www.thealternative.org.uk/dailyalternative/2018/6/28/raworth-doughnuts-critics.

United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2018). Summary for Policymakers — Global Warming of 1.5 oC. [online] Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm/