[This week’s guest post comes courtesy of the Sustainability team’s own Justin Fisher, who recently completed an MA in Science, Technology & Medicine in History. It is a guest post because he didn’t write it at work. The views presented do not necessarily reflect those of King’s Sustainability. See?]

Recently I had the good fortune to attend the launch of Dark Mountain Vol. 6 at Farringdon’s Free Word Centre. If you’ve not heard of the Dark Mountain project before, you’d be forgiven. Project co-founder Dougald Hine quipped at the event that when he asks people how they found Dark Mountain the answer is typically: ‘Well, it was late at night, and I was on the internet…’ Dougald admitted that this is exactly how he came to know the project’s other founder, Paul Kingsnorth, and I can confirm that this was the case for myself one night last December. It all might sound rather sinister. Launched a little over five years ago with a manifesto entitled ‘Uncivilisation’, Kingsnorth and Hine explicitly reject the dominant narratives of our society and are trying to facilitate the creation of new ones. Dark Mountain has become a powerful collective of artists and writers aggressively exposing the absurdities and contradictions of how modern society frames its relationship to nature. Above all else, it is showing the power of words and images in framing how we interpret and understand the world, and our place within it. They’re trying to tell new stories. They’re trying to destroy the ‘myths’ that sustain our society and drive our present crises: growth, progress, nature and civilisation. ‘We tried ruling the world; we tried acting as God’s steward, then we tried ushering in the human revolution, the age of reason and isolation. We failed in all of it, and our failure destroyed more than we were even aware of. The time for civilisation is past.’ Harsh words, indeed. But, are these not harsh times?

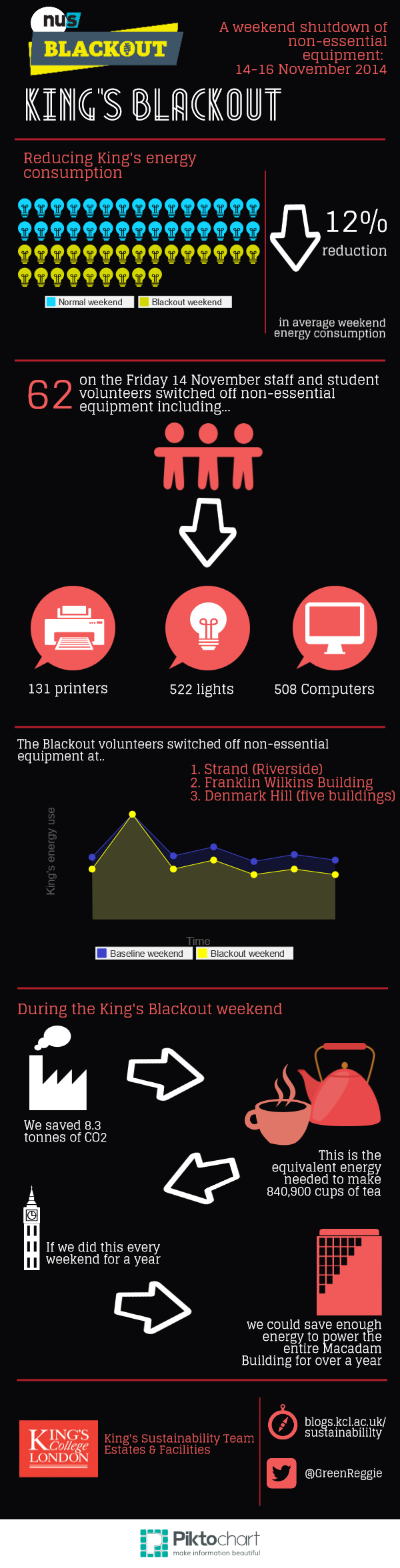

Before moving to London a little over a year ago I was broadly concerned about a number of environmental issues, and I made a conscious effort to do my part and encourage others to do theirs in reducing the environmental impacts of our lifestyles. I did the usual things like ditching my car for my bike, championing recycling and composting and ensuring that all lights and computers were turned off at work after every shift. But true change was surely beyond my grasp and not even on my radar. I was a History graduate working at a bookshop, not a climate scientist. As far as I was concerned, and as silly as it sounds to me now, environmentalism was a thoroughly scientific endeavour – one that I was deeply interested in, but not one that I could do very much about. And that was okay because I had some great scientifically-minded people in my life to take care of it. All I had to do was worry about it.

Then I began my MA at King’s last autumn, and, given my sympathies, the first module I enrolled in was environmental history. I had never encountered this before and was intrigued by what it might entail, and I quickly discovered what an important role the arts and humanities have to play in confronting the problems that we face. It was revelatory. I began to realise that as important as the science is, stories are equally so as they completely inform the way we interact with the world around us. One of the jobs of environmental history is to scrutinise these stories; to frame, un-frame and re-frame them; to examine how we have affected and been affected by our surroundings and what has driven that interaction. Finally, I felt like I had a place in this struggle, a way in, an angle that I understood. Graphs are great – I have some scientist friends who are giddy at the sight of them. But they don’t quite do it for me; I like words.

Dark Mountain, as I understand it, is all about words. And images. And sounds. It’s about casting off our assumptions, our pretenses and our underlying denial. It’s about re-framing our world. And it asks really tough questions. In an intriguingly titled article published by Orion magazine in 2012, ‘Confessions of a Recovering Environmentalist’, Kingsnorth took aim specifically at modern environmentalism, and especially its focus on ‘sustainability’. He asserted that sustainability, as it is commonly thrown about, ‘means sustaining human civilization at the comfort level that the world’s rich people—us—feel is their right, without destroying the “natural capital” or the “resource base” that is needed to do so.’ He went further:

This is business-as-usual: the expansive, colonizing, progressive human narrative, shorn only of the carbon. It is the latest phase of our careless, self-absorbed, ambition-addled destruction of the wild, the unpolluted, and the nonhuman. It is the mass destruction of the world’s remaining wild places in order to feed the human economy. And without any sense of irony, people are calling this “environmentalism.”

I have struggled with that article ever since reading it. It’s hard to not take what Kingsnorth says straight to the heart. But, here I am, working for the Sustainability team. And so I sympathise too with George Monbiot, a friend of Kingsnorth’s who has been openly critical of Dark Mountain and what he interprets to be climate-defeatism. In fact, I have an abundant amount of hope for what this crisis means for humanity and our world, despite the powerful interests in opposition, seeing it as an opportunity to completely shape our future – an opportunity that doesn’t come around often. It’s beyond clear that the way we operate cannot continue, and we undoubtedly need to figure out how to live sustainably. But it is indeed important to question what narrative is driving that push for sustainability. Is it a desire for business as usual, minus the carbon? If so, then Kingsnorth has nailed it – it’s a futile exercise. If, however, it’s taken as an opportunity to re-orient our understanding of the world, and of our place in it, then there is plenty to be hopeful for.

So yes, the science is clear. And it’s very scary. Yet we still hesitate to change. What’s the missing link? The stories we tell – of growth and development, of humans and nature – must have something to do with it. What does this mean on an individual level? I’m not entirely sure yet, but I suppose to start with it means questioning the stories that are driving my own life. It means asking what is truly most important to me, and what I can do about that. It means not accepting that there is only one way forward, but many choices ahead.

I think it means we can change.

– Justin Fisher (justin.fisher@kcl.ac.uk)