PhD researchers in the English department organise many conferences throughout the year. We asked current PhD researcher Julian Neuhauser, co-organiser of “The Early Modern Inns of Court and the Circulation of Text” with newly-minted Dr Romola Nuttall, to reflect on what inspired the conference and the various other events that are set to take place this summer.

By Julian Neuhauser, PhD candidate in the English Department

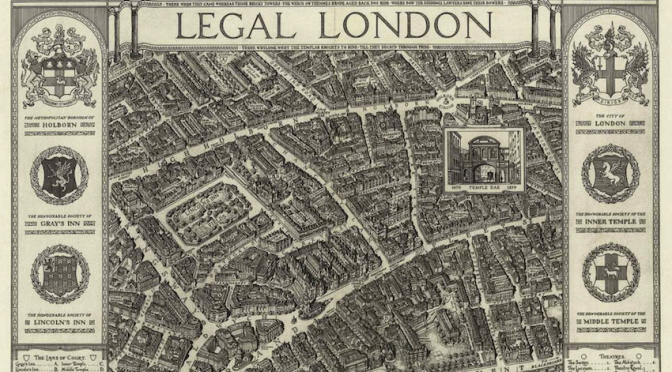

Since their establishment in the 14th century, the Inns of Court have been at the centre of legal scholarship and practice. Thought of as the ‘third university’, the Inns attracted graduates of Oxford and Cambridge who wanted to professionalise as lawyers and politicians. These student members of the Inns brought with them the habits and forms of sociability that they learned at university, including their socio-literary activities.

In order to investigate the literary history of the Inns of Court, I have been co-organising, along with Romola Nuttall (who defended her thesis at King’s in 2018), a conference called “The Early Modern Inns of Court and the Circulation of Text”. The conference will pull together cutting edge, materially-grounded, and culturally critical literary scholarship about the Inns, and we are also arranging a whole host of events around the papers and keynotes.

Romola was keen that we think about how to incorporate the Inns’ tradition of holding revels into our program. Revels were opulent and mirthful events, held annually around Christmas. They included lavish dinners, student run plays, and flyting – that is, combative (though usually well-spirited) extemporaneous oral jousting.

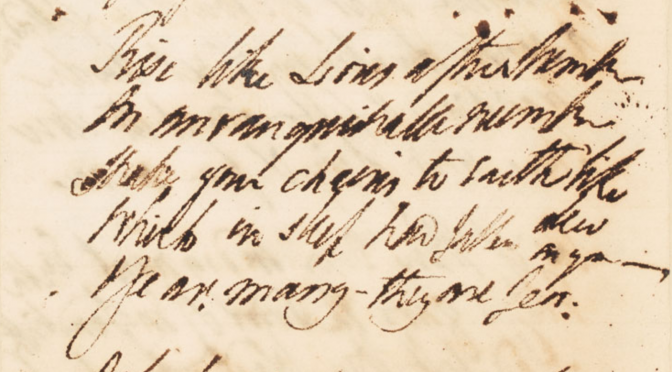

On the occasion of a particularly riotous Middle Temple revel in 1598, the poet and Middle Temple man Sir John Davies smashed a cudgel (like a Quidditch beater) over the head of fellow poet and lawyer Richard Martin. The event resulted in Davies’ ban from Middle Temple, but it also prompted him to return to New College, Oxford and, perhaps as an act of self-reflective contrition,[1] compose his poem Nosce Teipsum (‘Know Thyself’, check out an excerpt here.) Continue reading Presenting the Early Modern Inns Of Court and the Circulation of Text