by Emrys Jones, Lecturer in Eighteenth-Century Literature and Culture, and host of Pop Enlightenments Listen on Soundcloud and iTunes.

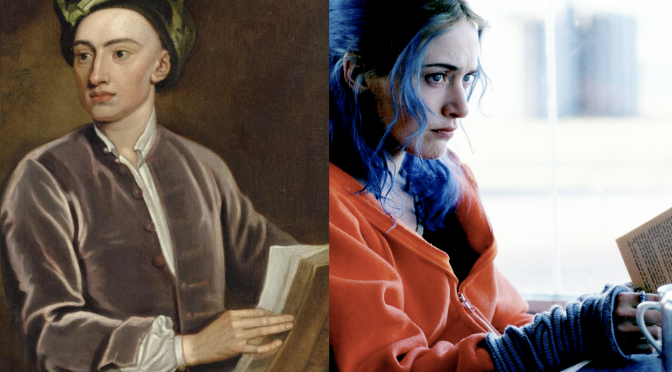

Earlier this year, I received what might be my favourite ever comment from an anonymous peer reviewer. It was regarding an article I had written for Literature Compass surveying recent scholarship on the eighteenth-century poet, Alexander Pope. I had offhandedly remarked in the essay that Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, the 2004 film written by Charlie Kaufman and directed by Michel Gondry, was Pope’s moment of greatest visibility in modern popular culture.

I didn’t think this would prove too controversial. The film takes a line from Pope’s Eloisa to Abelard (1717) as its title, and has one of its characters quote that line as part of a larger extract from the same poem. But the peer reviewer—amiably, it must be said—disagreed. Had I considered the Elvis song, ‘Can’t Help Falling In Love’, with its assertion, cribbed from Pope but attributed to generic “wise men”, that “fools rush in”? Had I watched the 1997 film—a Friends-era Matthew Perry vehicle—that took its title from that same line of poetry (Essay on Criticism, 1711, l.625)? I was sorely tempted to rewrite the whole article at this stage, to turn it into a lengthy dissertation on Pope’s importance for the romantic comedy genre. Hope Springs, anyone? But instead I stuck to my guns, politely insisted on Eternal Sunshine’s pre-eminence, and resubmitted the essay.

This maybe doesn’t sound like the peer review process at its finest. Rather than a serious scholarly to-and-fro resulting in an improved article, it was a manifestation of something like fan culture, an amusing quibble that one might imagine discussing in the pub sooner than the lecture theatre. However, as Pope himself wrote, “trivial things” can give rise to “mighty contests” (The Rape of the Lock, 1712, l.2), and for all that I didn’t end up taking the peer reviewer’s advice, I was grateful for the exchange as a distillation of pop culture’s interest and importance for scholarly practice.

It might not matter, or it might be an impossibly subjective conundrum, where Alexander Pope’s influence is felt most forcefully in today’s media landscape.

What does matter is that literary historians are open to the broader questions of how history is represented in popular culture, whether we see our concerns reflected in history or define ourselves against it.

This is where my recently-launched podcast, Pop Enlightenments, comes in.

The idea is a fairly simple one, stemming from work that I’ve done for the last five years as editor of the British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies’ reviews site, Criticks. Having seen the current wealth of pop cultural material inspired by eighteenth-century history—from the stage success of Hamilton to the televisual exploits of Poldark and Harlots—I set out in the podcast to discuss what the so-called age of enlightenment looks like and what it means to us when packaged for mass consumption today.

At the time of writing, the podcast is nearing the end of its eight-episode first season. In each episode, I’ve been joined by a guest to discuss a particular theme of the eighteenth century’s modern representation. We’ve covered piracy in the Pirates of the Caribbean movies, time travel as a way of accessing eighteenth-century history in Doctor Who, supernatural subversions of the Napoleonic Wars in Naomi Novik’s Temeraire novels, and the portrayal of the Jacobite political movement in the TV series, Outlander.

Throughout the podcast, I’ve been trying to avoid a stance that is either too reverential towards eighteenth-century history or too patronising towards modern engagements with it. The intention of the project is not to identify some glorious, authentic historical moment and then expose how far contemporary re-creations fall short of it. Actually, what I love about the eighteenth century is how tawdry and popular so much of its own culture was, how its own claims to enlightened wisdom or creative triumph were already mostly suspect, contaminated and compromised by the demands of a burgeoning cultural marketplace.

I would argue that the eighteenth century gave us the very idea of popular culture as we tend to recognise it today. A historian who looks with disdain on the disposability of twenty-first-century culture is prone to misunderstand the very anxieties and fixations that came to define the vast majority of artistic endeavours from the late seventeenth century onwards. I devote a fair chunk of the podcast’s introductory episode to discussion of an IKEA advert not because I’m being gratuitously quirky—and not because I’m a particular fan of the IKEA ‘experience’—but because it’s exactly what a great many eighteenth-century cultural commentators would themselves have done.

Spoilers for a fifteen-year-old film and a three-hundred-year old poem: spotless minds aren’t all they’re cracked up to be. Neither are spotless historical narratives.

Perhaps that is part of the reason that I wanted to mention Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind in my Pope article. It is both an appropriation of eighteenth-century poetry and a musing on the problems of historical appropriation itself; a film about amnesiacs who must confront the inaccessibility of the past and learn to construct a relationship with it as best they can nonetheless. That is also what the Pop Enlightenments podcast is trying to achieve: an era made fitfully visible through its peculiar, partial afterlives.

Popular culture binds us to the eighteenth century more strongly than ever before. It also reminds us, continually and productively, of that era’s distance.

The first season of the Pop Enlightenments podcast, in association with KCL’s Centre for Enlightenment Studies and the British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies, is available on Soundcloud and on iTunes. Further episodes will follow in 2019.

Featured image: composite image of ‘Portrait of Alexander Pope’, Studio of Godfrey Kneller, c. 1716, and Kate Winslet in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, dir. Michel Gondry, 2004.

You may also enjoy

Clare’s Pettitt’s ‘Cottonopolis Cut Down: An English Atrocity and Its Far-Reaching Consequences’

Angela Lee’s ‘The Political Day in Georgian London’

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.