by Ruth Padel, Professor of Poetry. Emerald, published by Chatto & Windus, is her 11th poetry collection.

“Never be afraid of saying you like poetry,” Jeremy Corbyn told thousands of people at Glastonbury in 2017, after reciting the end of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s ‘The Masque of Anarchy‘:

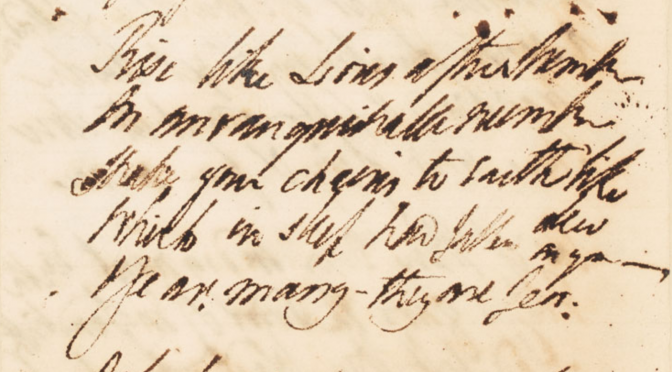

“Rise like lions after slumber … / Shake your chains to earth like dew … / Ye are many, they are few”.

Shelley wrote that poem – an apocalyptic vision of Britain’s destructive, corrupt, hypocritical rulers – after the Peterloo massacre in 1819, when the cavalry charged a peaceful crowd listening to speeches on parliamentary reform. Fifteen people died. “I met Murder on the way/ He had a mask like Castlereagh/ Very smooth he looked, yet grim;/ Seven blood-hounds followed him”.

In the following stanzas, the foreign secretary, prime minister and lord chancellor of the day accompany Lord Castlereagh, the leader of the House of Commons, through the groaning land, along with Anarchy, Shelley’s name for capitalism. The procession is stopped by a young woman called Hope (who “looked more like Despair”), who lay down in front of the horses.

I learned about Corbyn’s endorsement of poetry in discussion with Shami Chakrabarti in a “poetry and human rights” event at King’s College London, part of a series that highlights poetry’s conversation with all aspects of life, public or private, political or scientific.

“Poetry And” pairs an expert practitioner in a field such as film directing, neurobiology, or psychiatry for the homeless or returned soldiers suffering PTSD with poets seriously interested in that subject. The poets are inspired by details of the subject; the other speakers enjoy seeing their subject from poetry’s perspective, discovering how deeply it informs their work. The international lawyer Philippe Sands was delighted to find he had quoted so much poetry in East West Street, his bestselling quest for his family’s roots, which revealed the seeds of human rights law at the Nuremberg trials.

No poem ever stopped a tank. But by putting vivid words memorably together, in ways that resonate more loudly the deeper you go, poetry can address huge issues very powerfully.

Take, for example, Ben Okri’s poem on Grenfell Tower. Whether you are a scientist, shop assistant, IT consultant or personal trainer, a good poem offers a chance to log into yourself, to make new sense of your life and feelings while opening up to new ideas. It can speak to its audience on all levels, conscious and unconscious.

At the Edinburgh international book festival last summer, I read with Sean Borodale, whose poems were overtly about potholing. Mine were about my mother’s death, yet the audience found exciting connections between us. From wildly different starting points we were both suggesting ways of finding value in the dark.

I believe the need for poetry lurks in everyone. It bursts out in high emotion: many people read it, but often also want to write it when they fall in love, or a partner dies. “Look in thy heart, and write,” advised the Elizabethan poet Sir Philip Sidney. But to write poetry well, it helps to have learned to read it well; to feel at ease with poetry’s toolkit of sound and rhythm. “Well-versed” means “skilled”, as well as “familiar with poetry”. [Ed’s note, see Ruth Padel’s advice on ‘Four Steps to Penning a Poem‘ on the Writers and Artists blog].

For everyone to experience the value of poetry throughout their life, not just on Valentine’s Day or in times of mourning, teaching people to read as well as write it really matters. The box-ticking approach, characteristic of many exams today, misses poetry’s point. There are no right or wrong answers but rather explosive resonances, revelations unique to each individual reader, waiting to be heard.

English is compulsory at GCSE, but the system does not oblige children to study any course called literature, and certainly not one dedicated to poetry. However, projects such as England: Poems from a School, a 2018 anthology of poems by migrant children, showcase not only receptive pupils but inspirational teaching. They introduce children to beautifully made poems by other people, showing them that such poems are written for them and for everybody.

Shelley’s ‘Masque of Anarchy’ was too dangerous to publish until parliamentary reform was a real possibility in 1832. An earlier form of response to the Peterloo massacre came in 1821 when the Manchester Guardian was founded, set up to “enforce principles of civil liberty”. We still need both types of response to the tumultuous events of our day. Not only good journalism, but the good, resonant, reflective poem, which can help us pay attention to what’s going on in our hearts, and open us up to what our hearts see when they look at the world. And we need a population versed in poetry’s powers that is able to listen.

This piece was originally posted on the Guardian Comment is Free blog.

Featured image, Shelley, ‘The Masque of Anarchy’ autograph draft, 1819, British Library Ashley MS 4086.

Book your tickets for the forthcoming poetry evening ‘What Days We’re Having Now’, 7.30pm on Monday 4th February in the Strand Anatomy Theatre.

This touring show features three trailblazing young poets, Alex MacDonald, Ella Frears and Will Harris. The performance is specifically for under 25s, followed by a Q&A where students will have a chance to the poets about questions of craft and the writing life. Book your place here: https://tinyurl.com/what-days-were-having-now

Forthcoming POETRY AND… events at King’s College London

May 3rd 2019: ‘POETRY AND… the body’ with poet Linda Gregerson and physician and writer Gavin Francis.

May 14th 2019: ‘POETRY AND… the mind’ with poet Emily Berry and psychoanalyst Darien Leader.

Booking information will go live at this link when available.

You may also like to read:

A Day in the Life of the Humanities, by Alan Read, Lizzie Eger, Rowan Boyson, Josh Davies, Clare Lees, and Ruth Padel

Ruth Padel drafts ‘Capoeira Boy’

close: letter #1, by Ellie Jones and Bryony White

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.