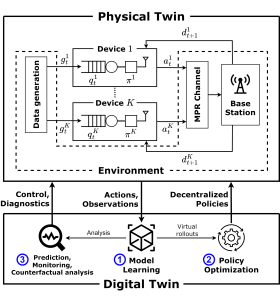

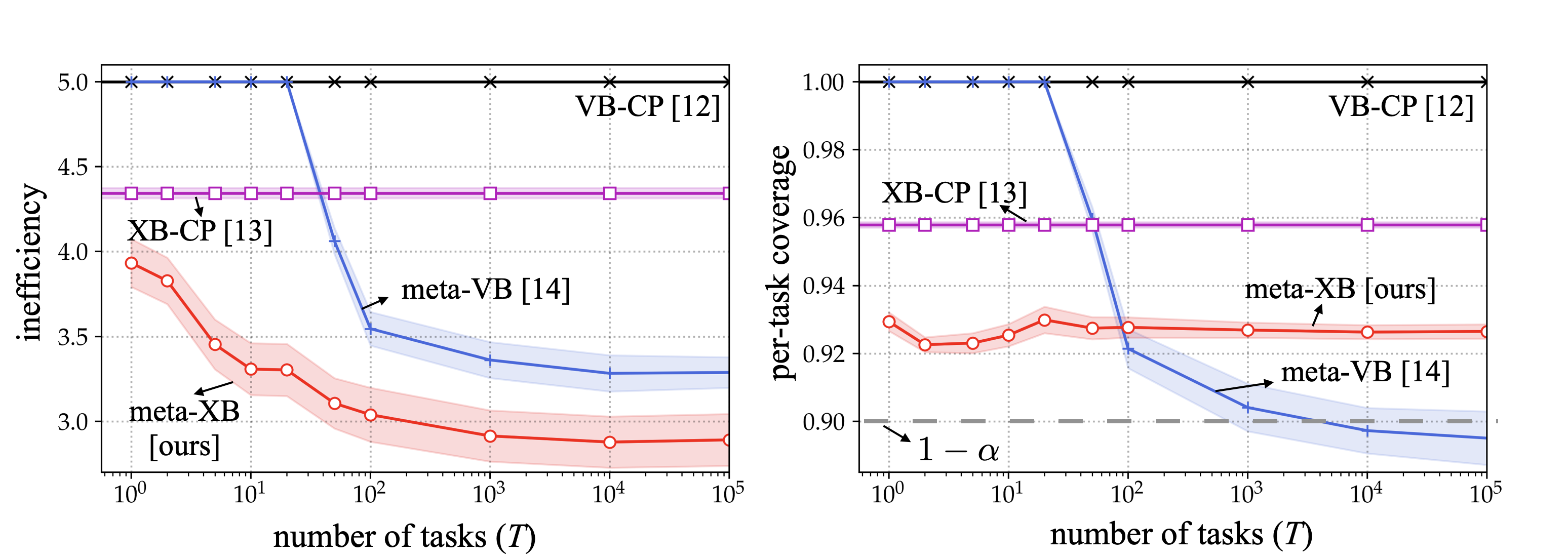

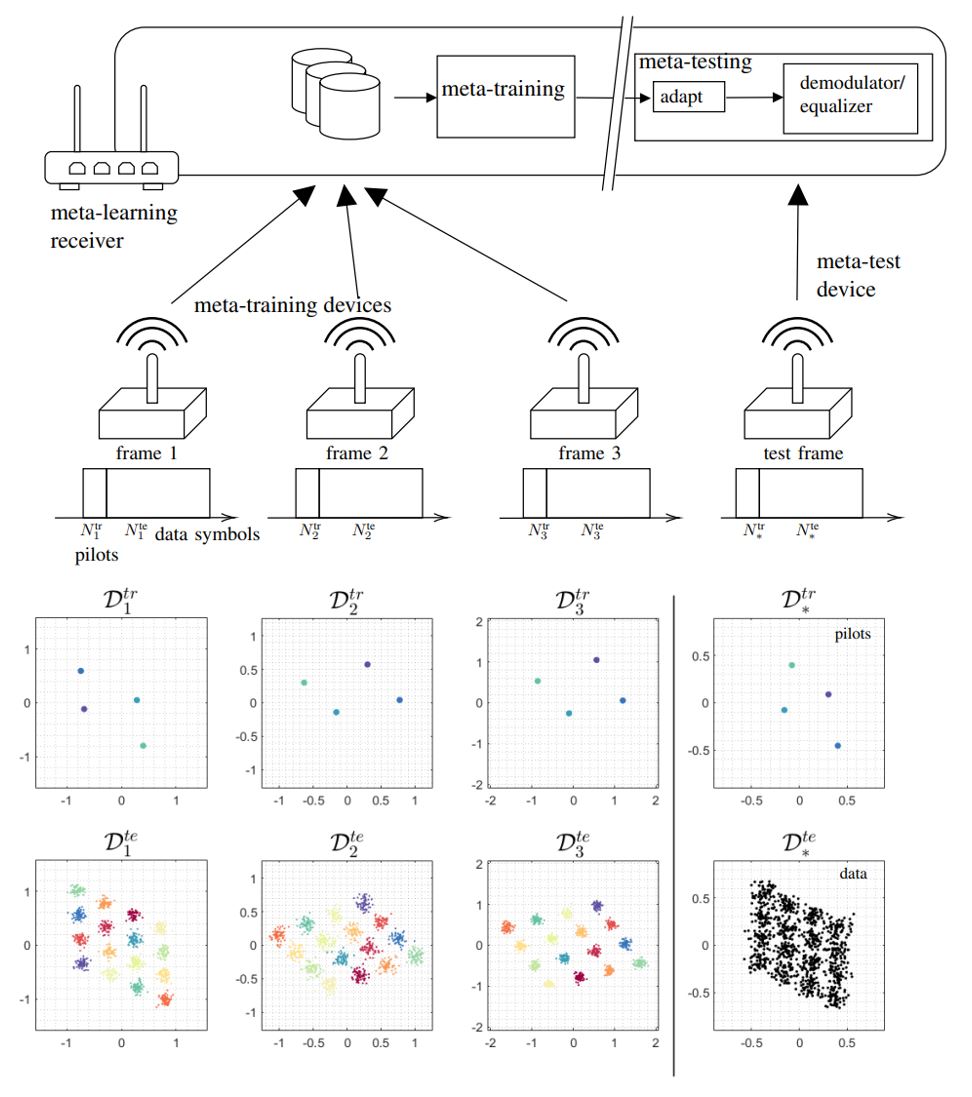

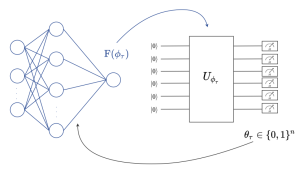

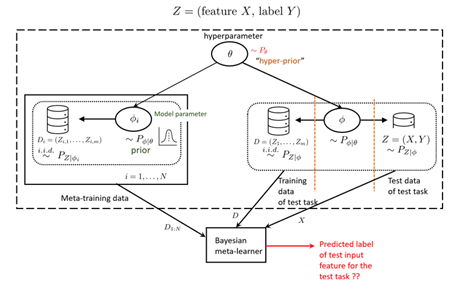

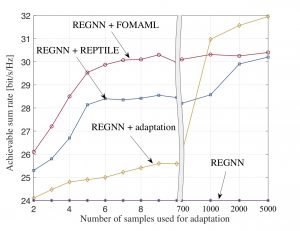

A digital twin (DT) consists of a high-fidelity virtual replica of a physical entity, the physical twin (PT), such that, in the words of DT pioneer Michael Grieves, “at its optimum, any information that could be obtained from inspecting a physical manufactured product can be obtained from its digital twin” [1]. Based on a fully automatized bi-directional flow of information [2], the DT uses the data collected from the physical world to maintain an up-to-date model of the PT, which in turn provides command and analysis functionalities to the PT (see Fig.1). With the ever-growing demand in communication resources, next-generation wireless networks will be required to adapt to a large number of scenarios, and DT platforms are increasingly seen as a promising data-driven solution to build intelligent wireless systems that can offer the necessary flexibility and responsiveness.

As depicted in Fig. 1, in a recent work to be presented at the IEEE International Conference on Communications, we consider a DT that autonomously learns a model of a wireless network, providing a safe sandbox environment for network optimization and analysis, while also enabling monitoring and prediction features. The main motivation for our work stems from the realization that, in real-world scenarios, it is challenging to transfer sufficient data to and from the PT in a way that “any information that could be obtained from inspecting the PT can be obtained from its DT”. In light of this, we propose to leverage Bayesian methods to learn a DT model that is aware of “what it knows” as much as it is aware of “what it does not know”; taking into account the epistemic uncertainty arising from limited PT-to-DT communication [3].

Figure 1 – The digital twin (DT) platform for the control and analysis of the communication system studied in this work. The physical twin (PT) consists of a group of K devices receiving correlated data and communicating over a shared multi-packet reception (MPR) channel. The DT platform operates along the phases of model learning (step 1) and policy optimization (step 2) ; while also enabling functionalities such as prediction, counterfactual analysis and monitoring (step 3) .

The Physical Twin

We consider a PT system made of a group of devices, referred to as agents, that attempt to communicate with a single base station (BS) over a shared multi-packet reception (MPR) channel [4]. Each agent is equipped with a limited-capacity buffer, and packet generation is taken to be correlated in-time and among agents. At any given time slot, each agent can take an action to decide whether or not to transmit a packet from their buffer, which can be received at the BS depending on the MPR channel dynamics. Upon packet reception, the BS transmits acknowledgement signals to the corresponding agents before the next time slot.

Agents cannot communicate with each other and each agent can only sense its local state, which contains information about its packet generation, buffer occupancy and BS feedback at a given time. Given the collective states and actions of all agents, the PT system evolves to a new state according to a transition distribution that is unknown to the DT and describes the packet-generation, buffer and channel dynamics.

The Digital Twin

Model Learning

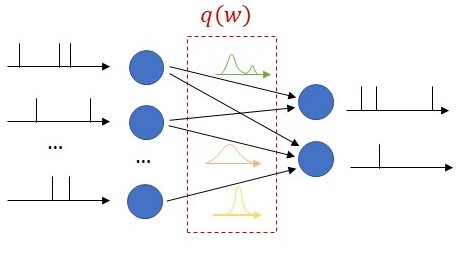

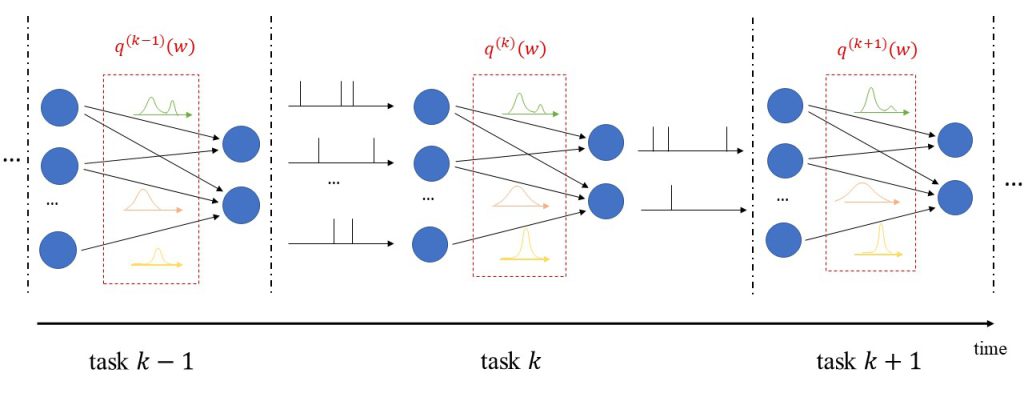

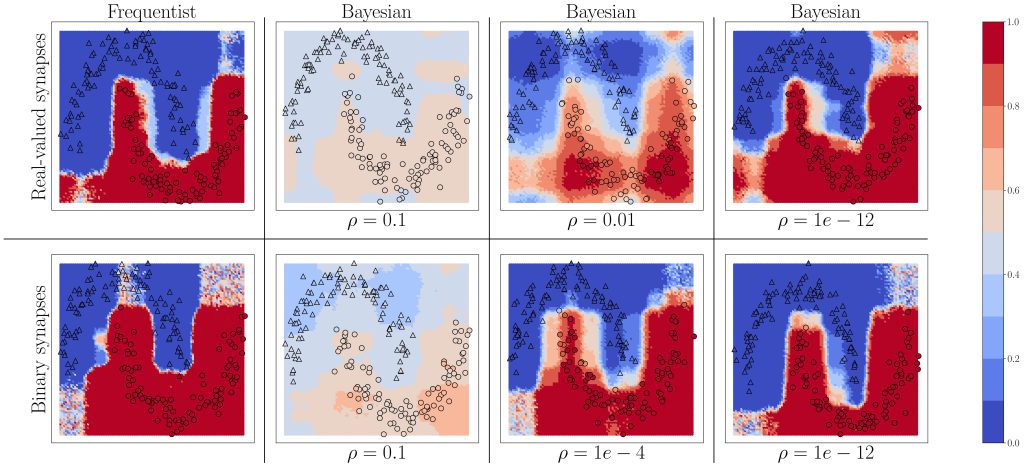

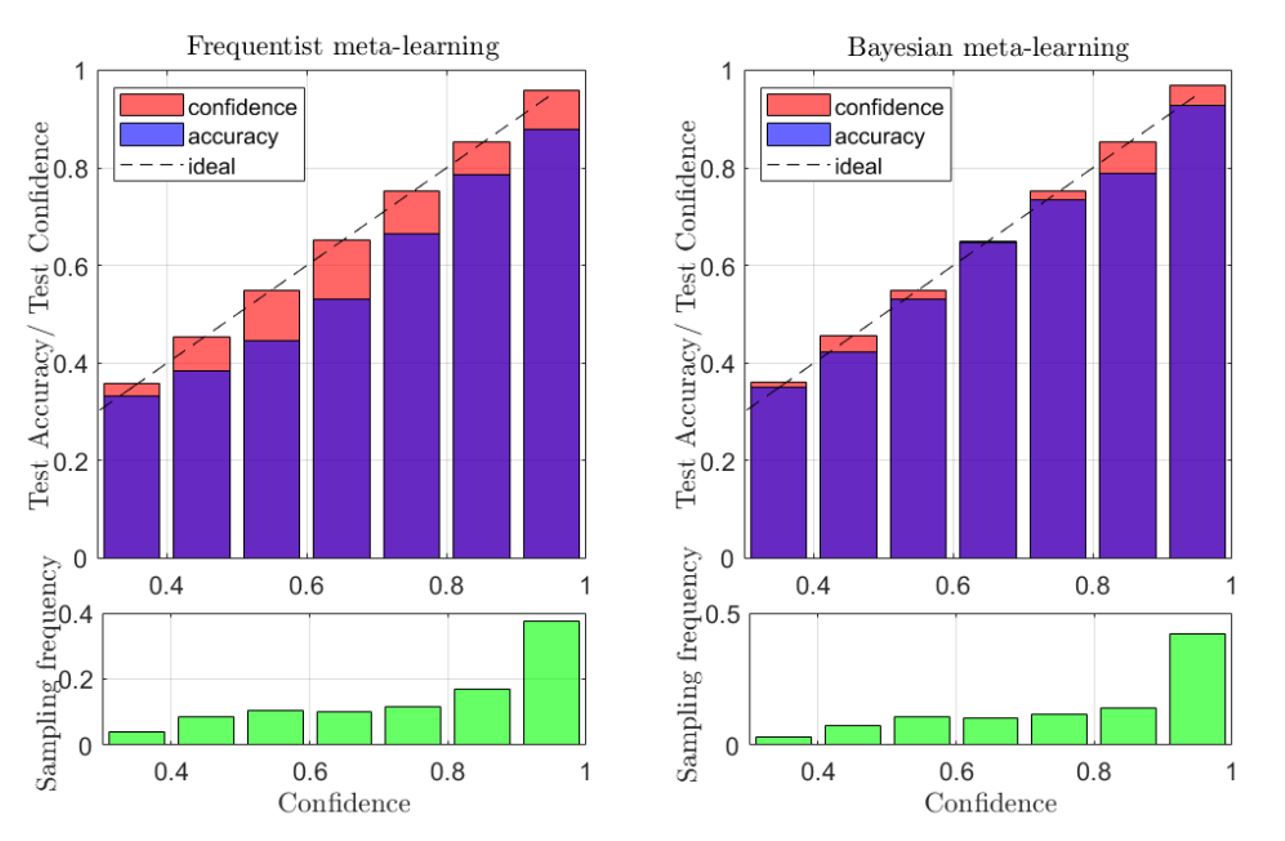

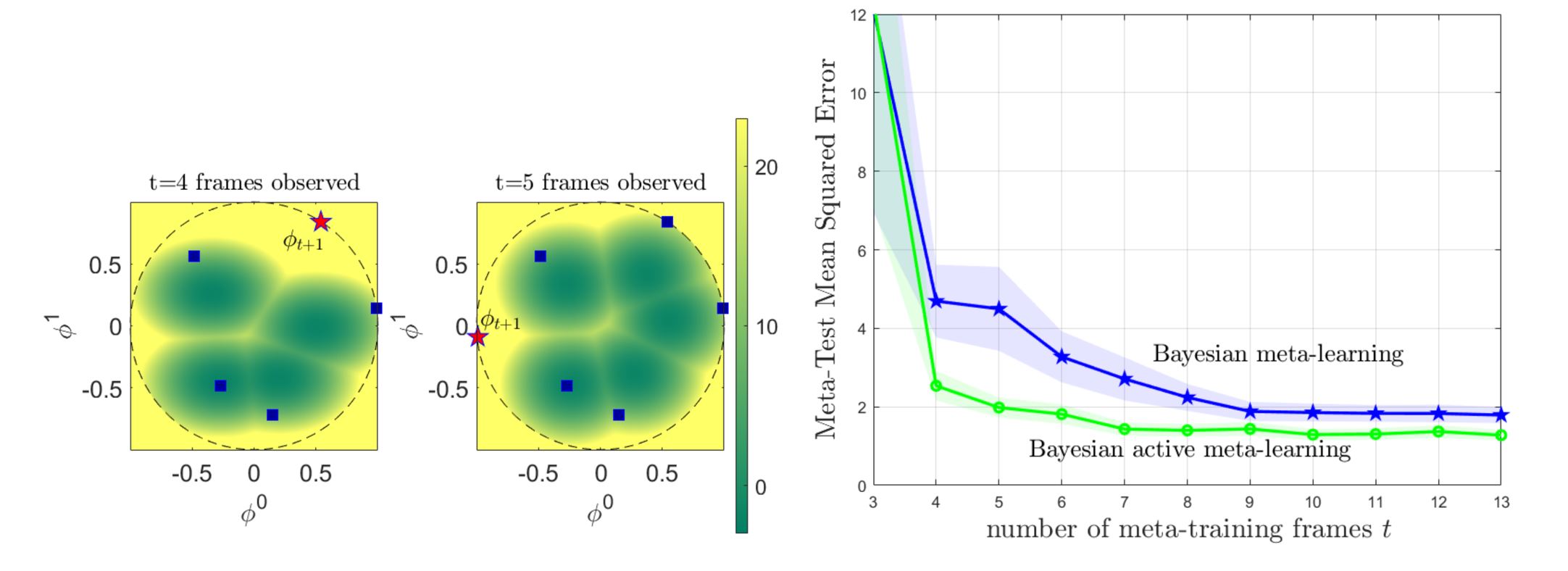

During model learning (step 1 in Fig. 1), the DT leverages sequences of states and actions collected from the PT to learn a parametric Bayesian model of the transition distribution. As opposed to frequentist learning, which only keeps the most probable model parameter, Bayesian learning keeps a (possibly infinite) ensemble of models, where the probability of each model is given by a posterior distribution. Given that all state variables are discrete, we represent the transition distribution using a categorical model and learn the corresponding posterior using the conjugate Dirichlet distribution [3]. In order to lower the spatial complexity of the model, we leverage prior information available at the DT about state transitions like data-generation clusters, known buffer dynamics, and symmetry of the MPR channel.

Policy Optimization: Safely Learn by Trial and Error

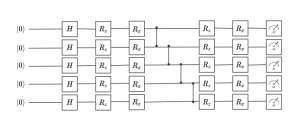

A medium access control (MAC) protocol at the PT can be established by providing each agent with a policy distribution that maps the sequence of locally observed states and actions into a new action. Using the learned model, we can safely asses new policies in virtual space by defining a reward function that yields positive values for desired behavior (e.g. successfully delivered packets) and negative penalties for undesired behavior (e.g. buffer overflow). Policy optimization (step 2 in Fig. 1) aims at providing an optimal policy to each agent that maximizes the expected sum of future rewards. This amounts to a Decentralized Markov Decision Process [5] problem that we tackle using the COunterfactual Multi-Agent (COMA) algorithm proposed in [6], in which we periodically sample a new transition distribution from the model posterior during training.

Monitoring: Let’s Agree to Disagree

After an initial model learning phase, the DT can provide monitoring features by checking whether newly received data fits previously observed transitions, or if it rather provides evidence of changed dynamics or anomalous behavior (step 3 in Fig. 1). To this end, we use a disagreement-based test metric that measures to which extent the Bayesian ensemble of models agree on the likelihood of the newly observed data. A large disagreement is taken as evidence of a large epistemic uncertainty compared to model-learning conditions, which in turn can indicate that the observation is anomalous.

Results

We evaluate the proposed DT platform on a simulated scenario consisting of 4 devices distributed across 2 data-generation clusters. The MPR channel allows for the successful delivery of one or two simultaneous packets; while more than two simultaneous transmissions cause the loss of all packets. Each device is equipped with a buffer with single-packet capacity.

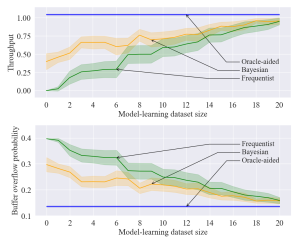

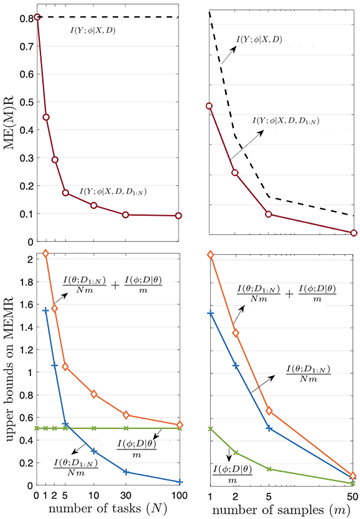

During policy optimization, we reward successfully delivered packets, while we penalize buffer overflows, caused by generating a new packet on an already full buffer. We analyze the performance of the policy trained inside the Bayesian model across different sizes of model-learning datasets, and compare it to a policy trained inside the corresponding maximum a posteriori (MAP) frequentist model, and to an oracle-aided policy that is trained using the ground-truth transition distribution.

Figure 2 – Throughput and buffer overflow probability as a function of the size of the dataset available in the model learning phase for the proposed Bayesian model-based approach (orange), as well as the oracle-aided model-free (blue) and frequentist model-based (green) benchmarks.

From Fig. 2, we observe that, in regimes with high data availability during the model learning phase, both Bayesian and frequentist model-based methods yield policies with similar performance to the oracle-aided benchmark. In the low-data regime, however, Bayesian learning achieves superior performance compared to its frequentist counterpart.

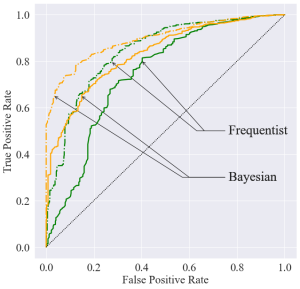

To asses the performance of anomaly detection, we assume that an anomalous event occurs where a device is disconnected, resulting in an anomalous packet-generation distribution in the corresponding cluster. We compare the performance of the disagreement metric using the Bayesian model to a log-likelihood criterion using the frequentist MAP model for model-learning datasets comprising 20 and 50 transitions and report the results in the receiver operating curves (ROC) in Fig. 3.

Figure 3 – Receiver operating curves (ROC) of the Bayesian (orange) and frequentist (green) anomaly detection tests for model-learning dataset sizes comprising 20 (solid lines) and 50 (dashed lines) transitions.

Bayesian anomaly detection is observed to uniformly outperform its frequentist counterpart, achieving a higher area under the ROC in Fig. 3.

For a more formal presentation of our proposed Bayesian framework for wireless networks DTs and more details on the experimental procedure, please refer to our paper at this link and to the extended version at this link.

References

[1] M. Grieves and J. Vickers, “Digital twin: Mitigating unpredictable, undesirable emergent behavior in complex systems,” in Transdisciplinary perspectives on complex systems. Springer, 2017, pp. 85–113.

[2] W. Kritzinger, M. Karner, G. Traar, J. Henjes, and W. Sihn, “Digital twin in manufacturing: A categorical literature review and classification,” IFAC-PapersOnLine, vol. 51, no. 11, pp. 1016–1022, 2018.

[3] O. Simeone, Machine Learning for Engineers. Cambridge University Press, 2022.

[4] L. Tong, Q. Zhao, and G. Mergen, “Multipacket reception in random access wireless networks: From signal processing to optimal medium access control,” IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 39, no. 11, pp. 108–112, 2001.

[5] F. A. Oliehoek and C. Amato, A concise introduction to decentralized POMDPs. Springer, 2016.

[6] J. Foerster, G. Farquhar, T. Afouras, N. Nardelli, and S. Whiteson, “Counterfactual multi-agent policy gradients,” in Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, vol. 32, no. 1, 2018.

Recent Comments