by Hailey Bachrach, PhD candidate researching gender in early modern history plays in collaboration with Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, @hbachrach.

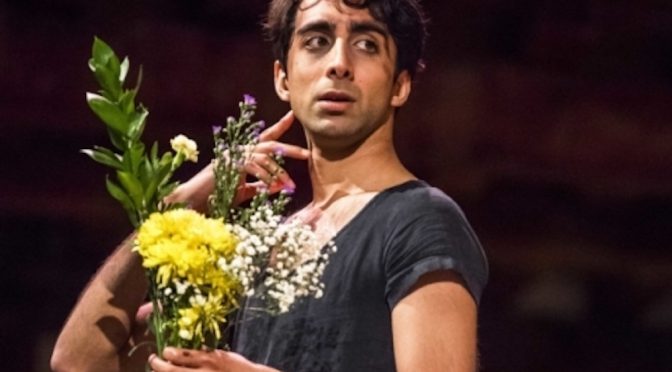

If you’ve heard of director Phyllida Lloyd’s Shakespeare Trilogy, which debuted at the Donmar Warehouse from 2012 to 2016 and was released in full on BBC iPlayer on 17 June, you’ve probably heard of its premise: it is performed by a company made up entirely of women, and framed as plays put on by a group of female prisoners. The three plays—Julius Caesar, Henry IV (the two parts combined into one), and The Tempest—are all intimately concerned with questions of masculinity and male relationships—fathers, brothers, sons—and are all notoriously light on female characters.

The prison framing device means, however, that they are not devoid of a female presence. There is no attempt at prosthetics or illusion in the production’s costumes. The actors wear prison-issue grey sweatpants and t-shirts, with accessories to designate changes of character. When Henry IV opened in 2014, Harriet Walter, who stars in all three productions, wrote that ‘our neuter prison garb … helps the audience put aside any questions of “Are they men playing women or women playing men?”… I would argue that when the cast are all women, we can look beyond gender to our common humanity’.

Continue reading Figuring Gender Difference in Phyllida Lloyd’s Shakespeare Trilogy