The Globe Theatre’s opening two shows of the 2018 season (and opening shows of the tenure of new artistic director Michelle Terry) are ‘gender blind’. It’s a phrase that’s deployed freely now in discussions about casting, usually referring to women being cast in male roles, usually in plays by Shakespeare and other canonical writers. But it’s not used with much consistency: Terry and her company use it to describe their approach to casting, in which both men and women are cast in roles that do not match their own gender, but play them as written. It has also been used to describe casting women in male roles that are then played as women.

The attention paid to gender in all of these productions seems to undermine what the phrase ‘gender blind’ clearly suggests: that the actor’s gender will go unseen.

What’s less clear is whether this lack of sight is meant to apply to the artists or the audience. It’s worth noting this term has been critiqued as ableist, but as it remains a phrase used by the production and criticism industries, we should explore the implications of its suggestion that we do not simply ignore, but literally do not see gender in these productions.

The headline ‘gender blind’ roles in these two productions are Jack Laskey as the cross-dressing heroine Rosalind in As You Like It opposite Bettrys Jones as her lover Orlando, and Michelle Terry herself as Hamlet, with Shubham Saraf as Ophelia and Jones again as Laertes.

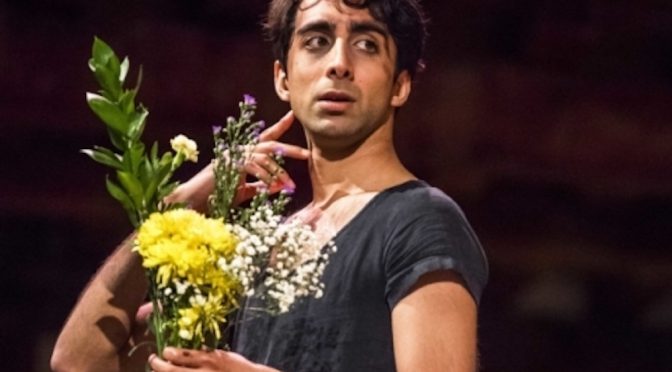

But who is meant to be ‘blind’ to this casting? There is no director in the collaboratively-cast ensemble, but these choices are too deliberate to have taken place ‘blindly’. For one thing, they have carefully avoided any same-gender actor pairs in the main romantic couples (though the comic clown pairing of Audrey and Touchstone in As You Like It does feature two male actors). Laskey and Saraf are both beautiful, and the two youngest men in the company. Though they don’t pad their chests, and Saraf never wears a wig, they are both clean shaven, slender and fine-featured rather than muscular or deep-voiced, or possessed of other stereotypical ‘masculine’ physical markers. Of all the men in the company, in other words, they are the least transgressive choices in terms of gender stereotypes.

The productions themselves make it clear that they hope the audience will be ‘blind’ to the performers’ genders. As Robin Craig, a friend and fellow PhD student, wrote on Twitter, ‘gender in these shows is entirely based on self-expression and identification. you say you’re a woman, you’re a woman’.

https://twitter.com/robin__craig/status/996520963050262533

Gender becomes yet another trait to be performed and accepted by the audience…

By not commenting upon or framing the cross-gender casting, the plays create, as Craig writes, a world in which the gender of the actor should be fully ignored in favour of the gender of the character. In addition to all the other elements of character an actor must enact—the facets of temperament or physicality or status that may or may not match their own inclinations or tendencies—gender becomes yet another trait to be performed and accepted by the audience, just as they accept that an Englishman is Danish, or an actor playing two different roles represents two different people.

However, both media coverage and live audience responses make it clear that many people don’t blindly accept the performance of gender. ‘What’s it like for a man to play Ophelia?’ WhatsOnStage asks, operating from the unstated assumption that of course it’s different for Saraf than it is for a woman. The night I saw Hamlet, while the audience had no apparent reaction to Saraf’s initial entrance in a dress, when he entered in a shift for Ophelia’s mad scene, some of his chest hair visible above the neckline of the gown, several pockets of the audience were overcome with uncontrollable giggles. A similar response of instant laughter greeted Laskey’s first entrance in gown and wig as Rosalind, even though neither character’s femininity is framed as exaggerated or comic.

So if the audience isn’t ‘blind’, what are they seeing?

Even if these are not the responses the creative team wants, we can’t just ignore them. We have to embrace a reading of these characters—and of supposedly ‘blind’ casting in general—that takes into account that many audience members in fact cannot and will not easily look past what seems to them to be a fundamental disconnect between who the gender of the actor as understood outside of the production, and the gender they are playing.

And just accepting the play’s casting without laughter doesn’t mean that one is therefore ‘blind’ to it. In these productions, gender is no more invisible than any other part of the actors’ bodies, as those bodies are one of the primary tools an actor uses to perform their craft. We see that Phebe’s hair is blonde even though Rosalind calls it black, we see that Hamlet has no beard even though he references one, we see that Celia is indeed the smaller when described as such.

Though members of the company have expressed hope that the productions indicate that we are ‘post-gender’ or ‘beyond gender’ as a society, simply put, we are not: ‘male’ and ‘female’ are still powerful determining factors in our society, and we still collectively hold stringent expectations about how, in particular, people of those genders should look.

Reading the characters’ gender as something actively performed rather than passively accepted opens up their identities to interpretation by the audience, filling the space between the desired utopian ‘post-gender’ world and the realities of our own deeply-ingrained social expectations with unique, individualized readings.

Some audience members, for example, speculated as to whether Rosalind was meant to be a trans woman. I read her as a cis woman whose emotional and physical ability to contain herself within the constraints of her gender and society was already hanging by a thread, her blaze of anger in the face of her uncle’s suspicion and her unruly sadness just glimpses of all the things she had to fight to suppress.

As he reveals in the speech that opens the play, Orlando too is keenly aware of the ways in which he falls short of the title of ‘gentleman’ to which he was supposedly born. He’s continually blundering: too defiant to his brother, too proud to the usurping Duke, too shy to the ladies, too violent in the forest, too careless as a mock-lover.

In Hamlet, the recurrent language of struggle to live up to a father’s legacy takes on a new tone when the young men at its core are played by women.

Jones’s Laertes and Terry’s Hamlet repeatedly have their ability to do right by their murdered fathers (both played by male actors) questioned. How can they live up to the patriarchal examples of these fathers, and how can they undertake the act of violent revenge? The one son who does achieve more than a Pyrrhic victory, who marches to avenge his father and lives to reap the benefits, is the invading Fortinbras—played by Laskey, his identity as performer now apparently harmoniously matched to the identity of his character.

Part of the reason these gendered disjunctions fit so smoothly into the plays is because Shakespeare himself was intimately concerned with these questions…

How one must labour to uphold in particular the demands of being a ‘gentleman’, a title to which one was not only born but also had to earn through behaviour, are of continual importance in his works. Well known, too, is his playful awareness of the artificiality of idealized femininity within a theatrical culture in which boys played women. Blurring the boundaries between genders to consider questions of beauty and sexuality is a preoccupation of dramatic writers across the period.

Reading the performance of gender, and understanding how the varying amounts of labour each actor must put into fulfilling their gendered role is integral to each character’s story, leads to questions that are too fascinating to go ignored. We may trouble the interpretive dominance of the artists’ vision by interrogating how audiences imaginatively fill the gap between actor and character for themselves. Allowing these plays to present gender not as invisible, but as something that is performed, not inherently tethered to the physical body of the person performing it makes for a more radical commentary on gender in our culture.

Featured image: Tristram Kenton/Shakespeare’s Globe

You may also enjoy:

Early Modern verbatim theatre, by Lucy Munro

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.