by Clare Pettitt, Professor of Nineteenth Century Literature and Culture, Department of English

“The first action of the battle of Manchester is over”, wrote Major Dyneley of the 15th Hussars, “& has, I am happy to say ended in the complete discomfiture of the Enemy.” At 4 pm on August 16, 1819, Dyneley was already back in the Hulme Barracks with his regiment. The “Enemy” was the 60,000 to 80,000 people, most of them textile workers, who had assembled that morning in St Peter’s Field on the outskirts of Manchester city centre, to hold a peaceful demonstration to protest against the Corn Laws, and to call for parliamentary reform. The Enemy was the people. And discomfited they had surely been.

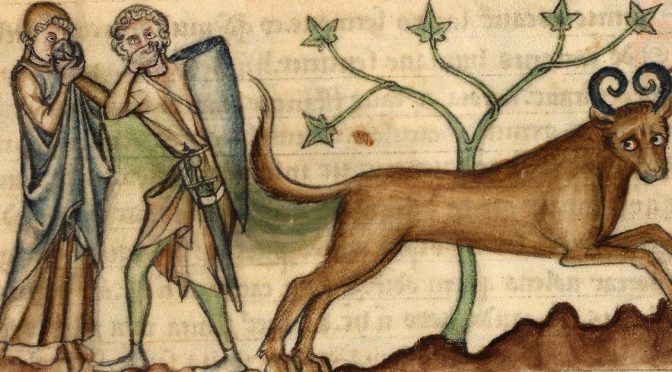

Henry Hunt, the orator who had addressed the meeting briefly before being arrested and beaten up, said that the Manchester Yeomanry, volunteers who made the first incursion into the crowd, before the Hussars, had “charged amongst the people, sabring right and left, in all directions. Sparing neither age,sex, nor rank”. It all happened very quickly. Ten minutes after the first charge, William Joliffe remembered that “the ground was quite covered with hats, shoes, musical instruments and other things”. Another eyewitness recounted that, “[s]everal mounds of human beings still remained where they had fallen, crushed down and smothered.

Continue reading Cottonopolis cut down: An English atrocity and its far-reaching consequences