by Melanie Marshall (Lincoln College, Oxford) and Daniel Starza Smith (English Department, King’s College London)

Every regime seeks to control the media. In the quest to dominate the official story, a repressive state might own the press outright (North Korea sits bottom of the 2018 World Press Freedom Index). It might sit tight with those who do (any British Prime Ministerial hopeful must bend the knee to Rupert Murdoch). It might restrict it (Google is making a limited search engine for China). Or it might simply undermine it: a racist tweet from Donald Trump is an effective distraction from ongoing scandals. Meanwhile, the American media’s ability to hold him to account is steadily eroded by accusations of fakery, disloyalty and partisanship.

Such tyrannical controls are hardly new, and early modern England faced its own media restrictions. Queen Elizabeth I famously claimed to want “no windows into men’s souls,” but with their reading material she proved less liberal. Throughout the last decade of her reign, her power waned and censorship tightened, until in 1599 the so-called Bishops’ Ban made the printing of satire a crime. Yet satire thrives on subversion, and the inflammatory material of the 1590s circulated away from the eyes of the state’s press-licensers. Handwritten copies of mischievous material passed from sympathiser to sympathiser, engendering more copies as they went.

Just such a privately circulated manuscript emerged in December 2016. Working through a tin trunk of scraps at Westminster Abbey, Matthew Payne, Keeper of the Muniments, uncovered a small booklet written in an early seventeenth-century hand, containing a work by the poet John Donne (1572–1631). It proved to be a copy of Donne’s Catalogus Librorum Satyricus, known in English as The Courtier’s Library, a satirical list of fake books whose composition we can now date securely to 1603 or early 1604.

Can an obscure list of fake books really be so radical…?

Today, the Catalogus is among Donne’s least known works – it’s written mainly in Latin, and dense with obscure topical references. Certainly, it sits oddly alongside his modern reputation as a sexy and witty author of daring erotic and religious verse. But it seems it wasn’t much read in the author’s life-time either: the Catalogus isn’t found in printed form till 1650, two decades after Donne’s death, and only one other manuscript is known.

Indeed, Donne’s own attitude to his joke library list was far from celebratory. In a letter to his friend Sir Henry Goodere in 1603/04, Donne reveals that he was desperate to recall every possible manuscript of the Catalogus, and this within mere months of its composition. Incidentally, this is Donne’s sole surviving Latin letter, translated for the very first time in our article (Appendix III). His scandalous 1601 marriage to Anne More, his employer’s young niece, had brought social and professional exile, and left Donne financially broke. So when the opportunity arose for a lucrative trip with an encouraging patron, Donne was keen to go – but his first thought was that he must suppress this text. Clearly, Donne was afraid that, if Goodere was copying and circulating it onwards, the Catalogus would harm his reputation and prospects. Can an obscure list of fake books really be so radical? What could possibly make this self-described “rag” so dangerous?

The answer lies in the date. Elizabeth died in March 1603, ending a forty-five year reign in which she had built up an image-centred court, balancing favourites and factions, all centred on the person of the Queen. That system was swept away with the accession of a new King, Elizabeth’s cousin James VI of Scotland. He came with a new and very definite agenda. Long before he arrived in London to take up the throne, James VI/I was famed, feared, and fêted for one thing: his learning.

The so-called “Scholar King” was the author of multiple theological tracts. He had already been planning a new translation of the Bible in Scotland, and brought his aspirations with him to the English court.

As James I travelled down to take up his new throne, he was met by a delegation of a thousand English Puritans with an axe to grind: how would James’s new regime cater to the demands of the godly?

This political ambush, known as the Millenary Petition, gave James an excuse to launch a theological convention as the early showpiece of his reign. Unlike the autocratic Tudor monarchs, Scottish kings were known for encouraging a degree of consultation. The convention was planned for late 1603, but eventually deferred till early 1604 – in other words, exactlythe date-range in which Donne’s Catalogus was being composed.

However, the Hampton Court Conference was no free debate. The King sidelined vocal extremists in favour of prominent insiders, and quickly quashed theological positions which threatened his grip on power. A new translation of the Bible was launched – what would become the King James Version of 1611 – to drive out the Geneva Bible (and, ahem, its anti-monarchical footnotes) from all the homes and churches in the realm. James also commissioned a report of the conference, to be written by the notorious royal toady Edward Barlow. Reading the Catalogus in this context, we can start to understand better the satirical targets of Donne’s fictional books.

Was there ever a more pungent moment for a satire on learning? Of course, the foibles of scholars are always ripe for lampoon. But it’s the ways that scholarship is corrupted by political power that really inspire Donne’s attacks…

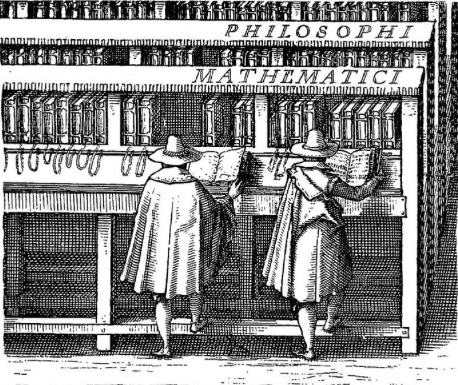

He attributes learned-sounding (but ridiculous) book titles to unlikely authors, mainly from among Donne’s own contemporaries in the public sphere. The list structure of the Catalogus means that the jokes come thick and fast. In the episodic, skit-like manner of Have I Got News for You or Saturday Night Live, one self-appointed boffin after another is swiped down – for crudity, stupidity, prolixity, treachery, vanity, venality, promiscuity… It’s a short text that packs in a huge amount of critique, and constantly gestures towards the impossibility of stemming the flow of sycophantic rubbish people will produce as they try to curry favour with power. Plus ça change. Yet the Catalogus has some very particular topical targets.

King James may claim that he wants the best minds to advise him, but what he really wants is the best minds to legitimate the political decisions he would have made anyway…

As Donne’s satirical introduction makes plain, it’s the appearance of learning that’s needed to get ahead in the incoming regime. Real intellectual motivations are laughably irrelevant. King James may claim that he wants the best minds to advise him, but what he really wants is the best minds to legitimate the political decisions he would have made anyway. Donne’s text is a handbook for the aspirant courtier in this new system. From 1603, yes-men and politicos will need to dress themselves up in a patina of scholarly expertise if they want to get ahead, but their pronouncements will be morally and politically vacuous. What better way to satirise them than with a list of books with titles but no contents or actual substance?

When truth itself is nothing but the whim of the King, can anything be said to have substance…?

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605 forced a crisis about who was truly faithful to the King, and which beliefs were compatible with being a loyal subject. Since James was both the political and the religious head of state, Catholics and Puritans alike were severely conflicted. But Donne foresees this problem the minute James takes the throne. Cunning diplomacy and strategic censorship will no longer be enough. Scholarship itself will succumb to fake media, Stuart-style – and truth will be what the King decrees.

The Catalogus is crammed with jokes about this, so let’s finish with one of them. In 1550, the Italian scholar Girolamo Cardano published a (real) work called On the Subtlety of Things (De subtilitate rerum). The new courtier’s library will have no need for such nuance, Donne implies. Instead, he recommends a new (fictional) work by Cardano: On the Nothingness of a Fart (Catalogus entry 23). When truth itself is nothing but the whim of the King, can anything be said to have substance? A trump is a nothing, and stinks all the more for that.

This blog begins to make literary sense of a recently discovered manuscript of a satirical work by John Donne, the Catalogus Librorum Satyricus, or Courtier’s Library. You can read our full article about the discovery here, another blog about the manuscript itself here, and (non-fake) newspaper coverage of the find in the Guardian. You can read the Catalogus itself (it’s only three pages long), in a parallel English/Latin translation by Piers Brown, here, pp. 858–63.

The blog is based on a paper we delivered at the John Donne Society Annual Conference 27 June–1 July 2018, University of Lausanne. We thank delegates for their useful critiques and suggestions, especially Piers Brown, Alison Knight, and Brent Nelson. Our RES article has been published open access thanks to funding from King’s English Department and the Arts and Humanities Faculty.

Featured image: Photo © MS Bodley Flanders – https://cdn.earlymusicmuse.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/bonaconMSBodley264.jpg

You may also enjoy:

Teaching Literature in the Age of Trump and Brevity: Some Reflections

Conspiracy and Enlightenment: ‘Speculations’ Series at King’s

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and not those of the English Department, nor King’s College London.