by Fran Allfrey, working on a LAHP-funded PhD about the cultural history of Sutton Hoo, and Beth Whalley, English and Geography PhD funded by the Rick Trainor Scholarship and Canal & River Trust.

‘The medieval’ in the contemporary moment

‘A Spot Called Crayford’ is a Heritage Lottery Fund project led by Crayford Reminiscence and Youth (CRAY), all about making the earliest Anglo-Saxon histories of Kent more accessible to school children. As part of the project, King’s medievalists led workshops in two Crayford primary schools, and a day-long journey to five sites in Kent associated with Anglo-Saxons stories.

One site we visited provoked questions that link to a research interest important to both of us: how ‘the medieval’ exists in the contemporary moment. Addressing collisions of archaeological enquiry, folk-stories, and over 1,000 years of writing about this place tested the possibilities of fun but critical activities, and asked us to confront the role of emotional responses to histories and spaces.

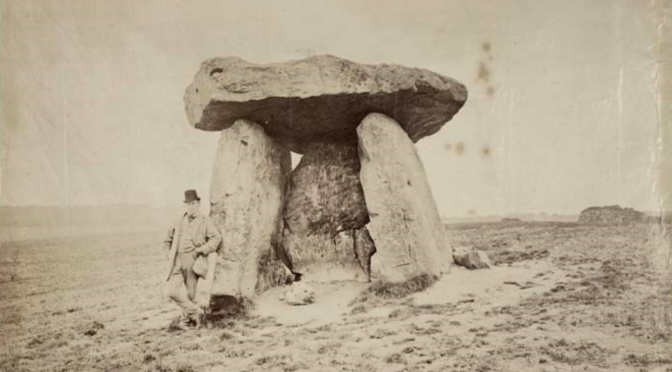

The site, or rather two sites, known as Kit’s Coty House and the White Horse Stone, are part of a scattered collection of Neolithic standing stones and barrows known as the ‘Medway Megaliths’. We had been asked by CRAY to lead activities for children aged 8-14 that engaged with these sites and their association with Horsa and Categern, two mythological fifth-century figures integral to the story of the adventus anglorum, the coming of the Angles.

Mixed medieval narratives of Horsa and Categern

The tale goes something like this:

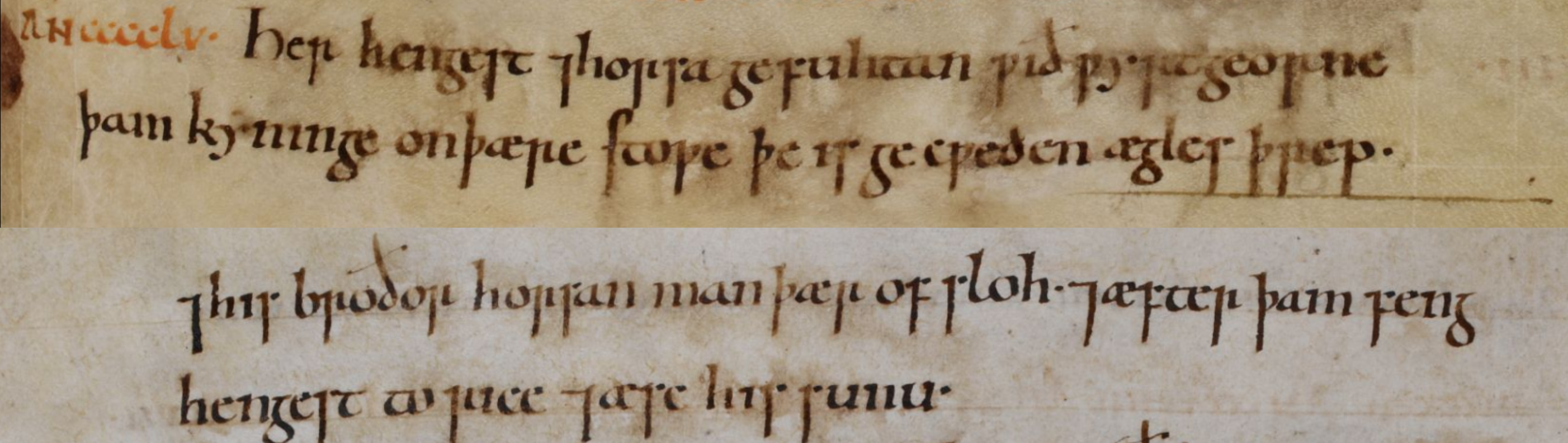

In the year 449 AD a British leader, Vortigern, invited the Saxons, Angles and Jutes to help Kentish folk fight against Pictish attacks. These auxiliary forces were led by the brothers Hengist and Horsa (whose names translate as ‘Stallion’ and ‘Horse’), who were descendants of Woden. They did help the British defeat the Picts, but quickly decided they wanted to settle on the island themselves. Further battles ensued between the British (Vortigern and his sons Categern and Vortimer) and the Anglo-Saxons. During one battle, at Aylesford, Horsa and Categern killed each other. In the eastern part of Kent, a monument was made to Horsa.

The Anglo-Saxons went on to win more land. The Britons succeeded in pushing the Saxons back. The Saxons were faced down by Ambrosius Aurelianus, or King Arthur…

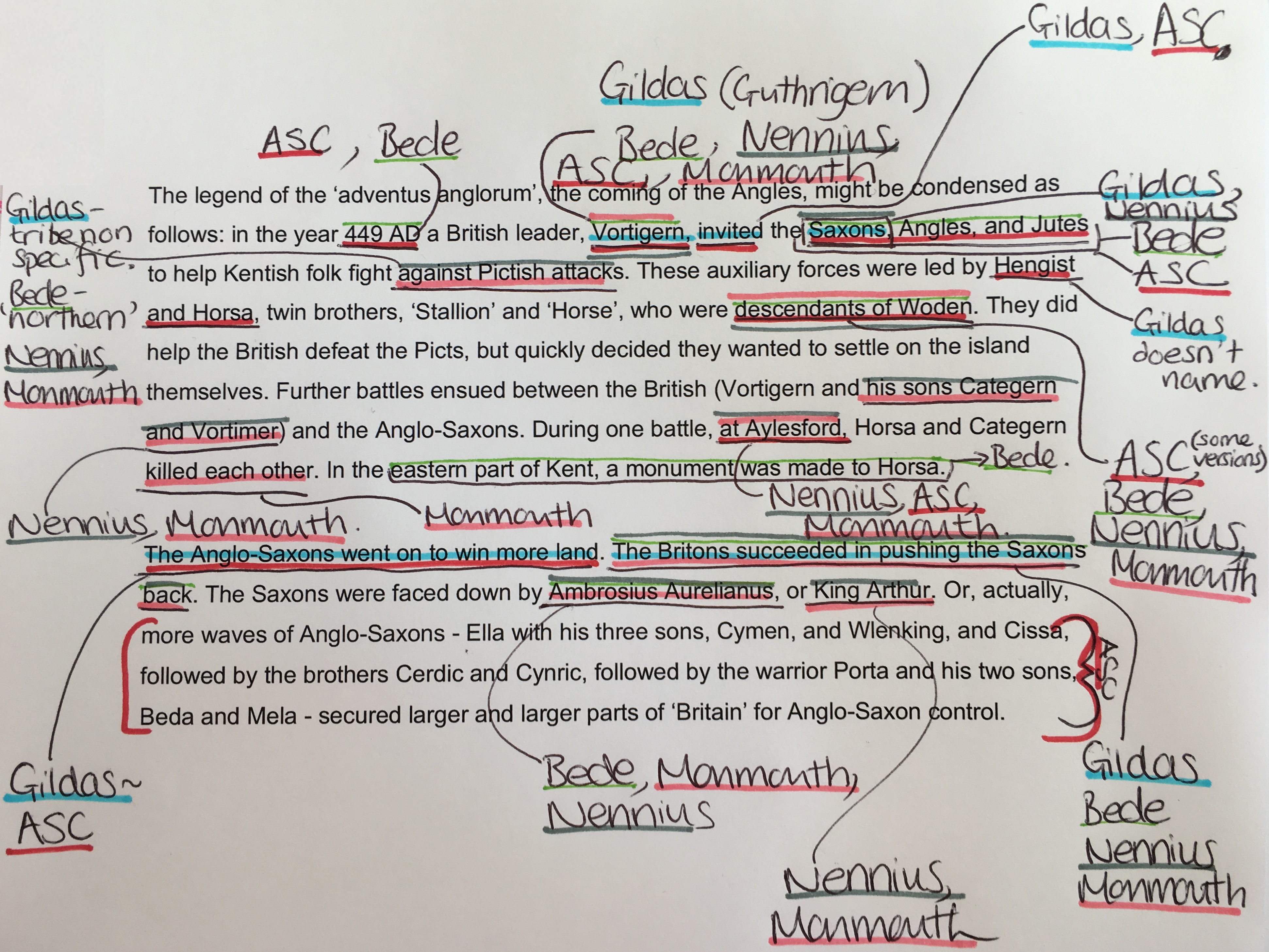

But this ‘simple’ narrative is a synthesis of five of the earliest extant texts: from Gildas (writing c. 550), to Geoffry of Monmouth (c. 1136).

Each of the texts has its own take on the events. But one thing the texts all have in common is a distinct lack of reference to Categern or Horsa’s tombs as big, old, stones.

In fact, in 1921, Nellie Slayton Aurner analysed these five (and six more) sources up to the 12th century, and found no mention of any stones or burials around Aylesford.

The person we think might be responsible for first linking the Medway megaliths with the story of Categern and Horsa is William Lambarde. A 16th-century lawyer, politician, and antiquarian, he also worked for Lawrence Nowell (the earliest-known owner of the manuscript that contains the only copy of Beowulf). Combining love of his home county with his interest in Anglo-Saxon history, Lambarde explains in his 1576 Perambulation of Kent how the fifth-century Britons:

‘erected to the memorie of Categerne (as I suppose) that monument of foure huge and hard stones, which are yet standing in this parish […] and now tearmed of the common people heere Citscotehouse.’

He continues that Horsa’s grave would not have been made with such stones, as ‘this fashion of monument was peculiar to the Britons’. With attention to toponyms, he suggests that ‘the memorie of Horsa was by all likelyhood left at Horsted, a place not farre off, and both then and yet so called of his name’, and resigns himself to concluding that the grave must be lost.

After Lambarde, many gentleman wanderers wrote guidebooks to Kent across the 16th to 20th centuries repeating the idea (with more or less conviction) that Kit’s Coty House was the grave of Categern.

The White Horse Stone

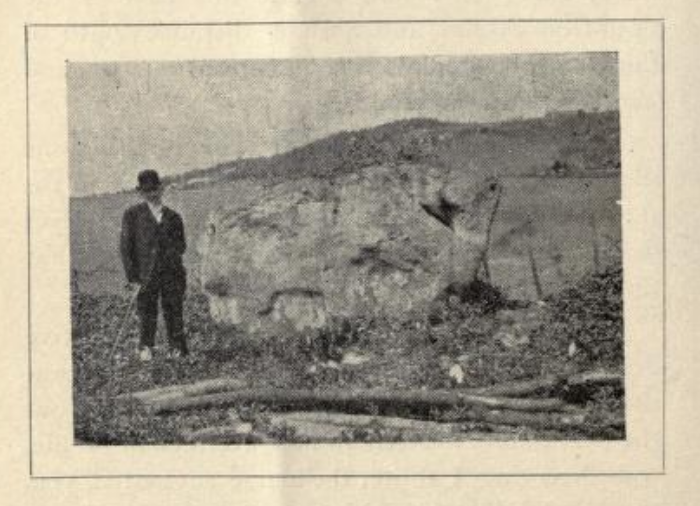

The White Horse Stone was slower to gain its role in Anglo-Saxonist mythology. In 16th-18th century accounts, Horsa’s grave is variously identified lost ‘near Horsted’, or identified as a ‘pile of flints covered in moss’ near to a farmhouse in the village. One writer insists that Kit’s Coty House was Horsa’s tomb, rather than Categern’s. If the White Horse Stone gets a mention in a guide book, it is a curiosity which gained its name because it ‘looks like a horse’.

Then, in 1834, in A Brief Historical and Descriptive Account of Maidstone and Its Environs, S C Lampreys insists that the standard of the Saxons was laid upon the White Horse Stone following the battle, and a new wave of speculations began. To complicate matters further, some guidebooks associate Horsa with the Upper White Horse Stone (to give it its full name), while others identify the now-destroyed Lower White Horse Stone as the mythological megalith.

20th-century archaeological work has found both megaliths to be 2,500-5,000 year old barrow or grave markers. Though extant texts show little interest in ancient sites, we could assume that the British and Anglo-Saxons may have noticed and repurposed these stones. The megaliths are barely two miles from the river crossing at Aylesford, not too far to carry a body. If we entertain the idea that Horsa and Categern were (or represent) real people, they could well have been honoured by being brought to these already-ancient landmarks. But we simply don’t have any archaeological or textual evidence.

There were already, then, a lot of possible questions to explore with the CRAY group. To complicate the narrative further, enter some of the most recent actors in the mythological network…

Pagan appropriation

Today, Google ‘the White Horse Stone’ and it becomes clear that the stone’s connection to Horsa is of special interest to pagan groups. One pagan-run website appears high on Google’s rankings, and is a key reference on the stone’s Wikipedia page. This particular group calls its members ‘Guardians’ of the stone. They have built steps from the footpath, spent time clearing litter and overgrowth, and lobbied local councils to prevent a mobile telephone mast being built nearby.

This group also consider the stone to be ‘the birthplace of England’, hold a belief in a heritage of the ‘English race’, and practice communion with ‘ancestors of the blood’ (see Ethan Doyle White’s ethnography for more on how pagan groups use the Medway stones in a variety of ways). This side of their beliefs is woven into their historiographic writing and environmental activism on their mini-site dedicated to the stone. They present themselves as philanthropic champions of cultural heritage, protecting the ‘forgotten’ history of Anglo-Saxon ancestors.

Sara Ahmed has identified how this is a common public face adopted by hate groups. Her analysis of how such groups justify themselves, ‘we do and say this because we love, not because we hate’ is useful here: this group presents themselves as driven by concerns of preservation and conservation.

Ahmed writes how white supremacists ‘imagine a subject that is under threat by imagined others’ in order to galvanise. We wonder what this group would identify as a bigger threat to the White Horse Stone: a proposed mobile telephone mast, or the promotion of other histories.

Reading texts, feeling the vibes

Although we weren’t in a position to assign Ahmed as prior reading to the youth group, we wanted to address how and why the stories of the early Anglo-Saxons and of the Medway megaliths have been shaped by personal ideologies. We wanted to ask everyone to consider what sort of world a given ‘history’ presumes or desires.

Looking at extracts from the five medieval texts, the children considered why people might choose to preserve stories from the past. They speculated about why the Saxons were presented as either evil marauders or brave heroes depending on the identities and biases of the authors.

We talked about what in the landscape might attract 17th-century writers to the sites. The children pointed out how the stones are prominent but strange, and so a 17th century antiquarian who knows about the Anglo-Saxons could be tempted to associate the stones with the stories of important local battles.

Someone made the great observation that the stones have an unusual ‘vibe’ – which is probably the most important thing to notice: that the feel of places influences how we understand them.

It was certainly very surprising to us to see how wooded the area around the White Horse Stone has become, compared to photographs from just over 100 years ago – the vibes must’ve been quite different.

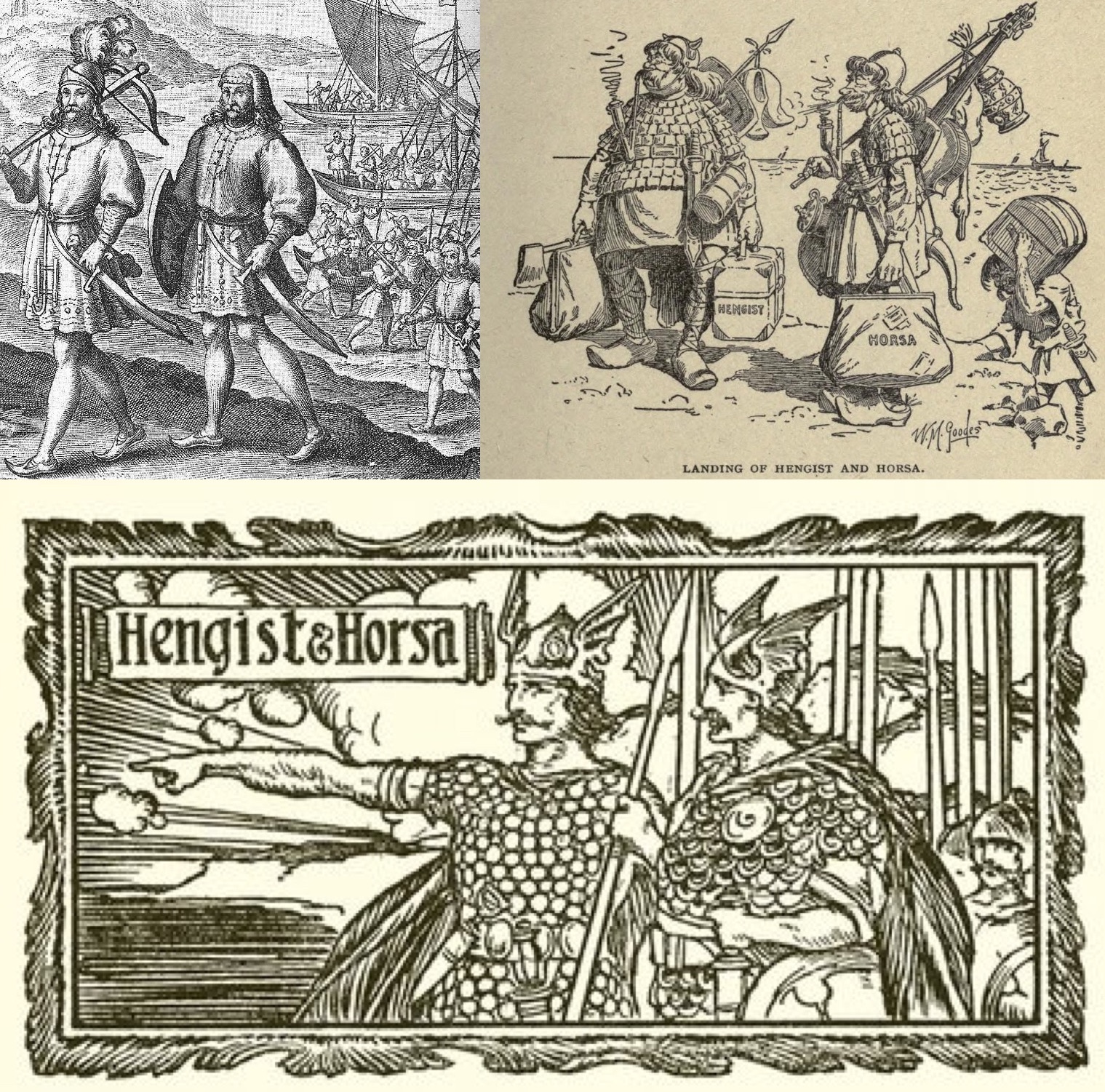

We used artwork of Hengist and Horsa as a way of discussing modern uses of the myth. The children thought carefully about why people might present history differently: whether they want to proudly amplify it or hide it, are seeking entertainment, or are religiously-motivated. They thought about reasons why these artists might want to change how history looks to fit their own ideas about what is ‘good’, ‘admirable’ – or what should be made fun of. They noticed how the style of each of these drawings showed Hengist and Horsa in various lights: from proud Vikings, to gentlemanly Renaissance-men, to clownish oafs.

The kids found it more difficult to think about how people today shape history as they tell it: perhaps we needed to provide more of-the-moment examples to show that this isn’t just a phenomena of years gone by.

Some users of the stone today would have the world believe that they have the greatest claim to its rocky form, transforming it into a sort of altar to their toxic blend of white supremacy and ethno-nationalism. Therefore, something we were keen to avoid was creating a ‘ritual’ around the stone. But, we did want to encourage the children to see the stone as a playful site of performance. Our final challenge was for everyone in groups of three to imagine and act out a scene from the White Horse Stone’s history or mythology. We saw the stone used for a game of hide-and-seek, as an actual horse ridden by a fierce warrior, and as the work of a perfectionist sculptor interrupted by meddling friends!

Palimpsests of history

We still feel some unease about our site visit – what would have happened had we stumbled upon a pagan ritual? Do we want to encourage people to associate the site with the Anglo-Saxons at all? We’re also still left with questions about the relationship that people who would distance themselves from organised white supremacy have to stories of the Anglo-Saxon past.

What does it mean for people to have a sense of ‘local pride’, to be invested in stories about the places in which they live, whether these stories stem from old remains or new folklores? What drivers might inspire an interest in the past that isn’t predicated on exclusionary narratives? How do we make the unknowable, the complex, as exciting as fantasy myths of named heroes and exploits?

We hope that our visit (and this write up!) was just one way to think with the stones about palimpsests of history, the messiness of mythology, and the strangeness (or comfort) of the ‘vibes’ that we get from places. There are stories to be told about the Anglo-Saxon past that show how everyone has a stake in them, but no-one has a claim to them. Throwing ourselves into encounters with texts, images, and places can unravel simplistic, closed, conclusions: and the conversations we had with the CRAY kids would be at home in the undergraduate classroom, the conference panel, or on the sofa after the next ‘Dark Ages’ documentary.

Featured image: AL2400:033:01 from archive.historicengland.org.uk ‘View of Kit’s Coty House sarsen group with a man standing in the foreground’, Flaxman Spurrell (1880).

You may also like to read:

Teaching literature in the age of Trump and Brexit, by Sinéad Murphy and Diya Gupta.

The Long Read: Medieval Women, Modern Readers, by Fran Allfrey and Beth Whalley.

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.