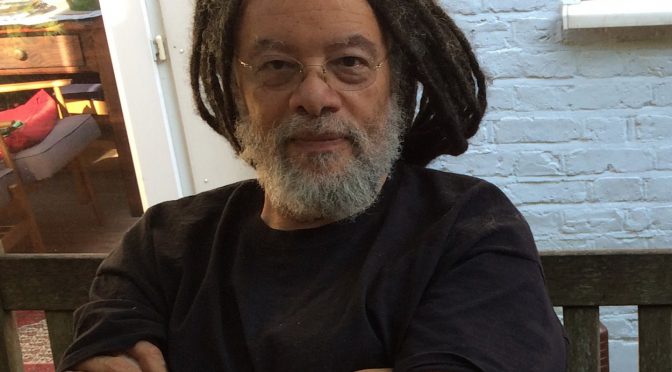

By Dr Gemma Miller, Department of English and Globe Education

The Shakespeare Academy has been running at King’s for the past three years and I am very proud to have been involved from its inception. In 2017-18 we reached over 350 Widening Participation students, continuing to develop close partnerships with teachers and pupils at eight London state-funded secondary schools, from Key Stage 3 to GCSE. We’ve also run Teachers Days with the London Shakespeare Centre.

My role as administrator and workshop leader involves liaising with the schools, creating the programme for the Academy study days, supporting my colleagues in preparing individual sessions and delivering workshops myself. I am particularly passionate about inclusive access to education: my brother and I were the first in our family to obtain degrees. I also believe that engaging with Shakespeare in an interactive and creative way can help to break down perceived barriers by making the plays seem more accessible.

All ‘national curriculum’ students study Shakespeare (two plays at key stages 3 and at least one play at key stage 4). Many of the pupils we work with are from Black or Ethnic Minority backgrounds, or come from families where their parents or carers have not attended university. We give these students access to university-style learning to give them a taste of what they can expect. This makes Shakespeare’s plays a valuable common currency to reach groups who are under-represented in tertiary education. Also, plays such as Macbeth and Romeo and Juliet deal with important social and political issues – power, love, inter-generational conflict, gang warfare – that are still relevant today. The plays are useful tools for thinking about wider social concerns that are universally recognisable.