by Fran Allfrey, working on a LAHP-funded PhD about the cultural history of Sutton Hoo, and Beth Whalley, English and Geography PhD funded by the Rick Trainor Scholarship and Canal & River Trust.

‘The medieval’ in the contemporary moment

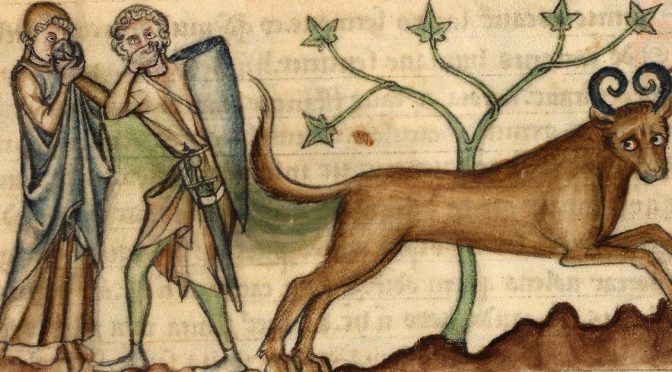

‘A Spot Called Crayford’ is a Heritage Lottery Fund project led by Crayford Reminiscence and Youth (CRAY), all about making the earliest Anglo-Saxon histories of Kent more accessible to school children. As part of the project, King’s medievalists led workshops in two Crayford primary schools, and a day-long journey to five sites in Kent associated with Anglo-Saxons stories.

One site we visited provoked questions that link to a research interest important to both of us: how ‘the medieval’ exists in the contemporary moment. Addressing collisions of archaeological enquiry, folk-stories, and over 1,000 years of writing about this place tested the possibilities of fun but critical activities, and asked us to confront the role of emotional responses to histories and spaces.

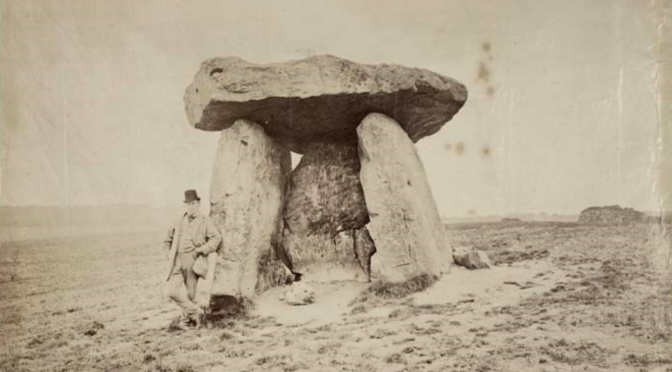

The site, or rather two sites, known as Kit’s Coty House and the White Horse Stone, are part of a scattered collection of Neolithic standing stones and barrows known as the ‘Medway Megaliths’. We had been asked by CRAY to lead activities for children aged 8-14 that engaged with these sites and their association with Horsa and Categern, two mythological fifth-century figures integral to the story of the adventus anglorum, the coming of the Angles.