by Gordon McMullan, Professor of English at King’s College London and Director of the London Shakespeare Centre

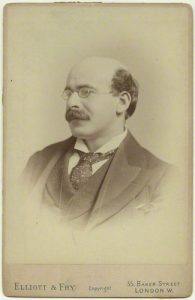

A little over a century ago, King’s English professor Israel (later Sir Israel) Gollancz –medievalist, Shakespearean and founding member of the British Academy – published a substantive commemorative volume to mark the Shakespeare Tercentenary of 1916. Grandly titled A Book of Homage to Shakespeare, it contains a hundred and sixty-six contributions – poems, essays, encomia – reflecting the pre-eminence of Shakespeare’s works in global culture: a poem by Thomas Hardy, a eulogy by John Galsworthy, a humorous ‘vision’ by Rudyard Kipling, a poem by a former New Zealand High Commissioner entitled ‘The Dream Imperial’, along with enthusiastic pieces by Shakespeare scholars and politicians from across the world.

Certain contributions stand out as expressing less normative world views – two in particular. One is a poem in Gaelic by future Irish president Douglas Hyde, in which (in a passage mysteriously omitted from the English translation…) he describes ‘Albion’ as ‘deceitful sinful guileful / Hypocritical destructive lying slippery’. The other is a piece entitled ‘A South African’s Homage’ by an unnamed writer who writes in Tswana, a language spoken mainly in contemporary South Africa and Botswana, also in Namibia and Zimbabwe – in other words, someone very different from what you might, in light of the array of overwhelmingly white establishment figures named in the table of contents, have expected.

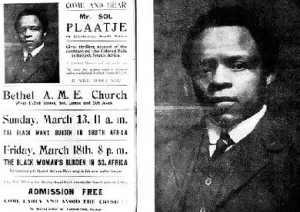

This unnamed South African was Solomon Plaatje (pronounced ‘ply-kee’), an intellectual, journalist, linguist, politician, translator of Shakespeare, writer of the first novel in English by a black South African and – as founding general secretary of the South African Native National Congress (later the African National Congress, Nelson Mandela’s ANC) – a major figure in South Africa’s liberation history.

In his contribution to the Book of Homage, Plaatje recounts his experience of reading Shakespeare’s plays, noting tongue-in-cheek that the first time he read The Merchant of Venice, he found the characters so realistic that he wondered ‘to which of certain speculators, then operating round Kimberley, Shakespeare referred as Shylock’. He also describes how, when he and his wife, a Xhosa speaker, first met, they communicated in English so as to express their ‘innermost feelings’ and he notes, deadpan, of the linguistic and cultural tensions that arose between their families, that ‘[i]t may be depended upon that we both read Romeo and Juliet’. In the essay, he quietly appropriates Shakespeare, deploying an engaging mix of resistance, playfulness and humour for a form of African self-fashioning by way of one of the most revered icons of English colonial rule and, in the process, situates Shakespeare as equivalent, not superior, to the African folk tale tradition.

It was in fact Plaatje’s contribution, more than those of the better-known writers represented in the volume, that reviewers, who found the collection as a whole uninspiring (the New Statesman called it ‘a tombstone for Shakespeare’), appreciated. The TLS reviewer suggested that when readers had worked their way through ‘the minutiae of the scholars, the rapture of the poets, [they may] wonder whether anything in the volume would have delighted Shakespeare so much as the paper in which a gentleman of the Chuana [Tswana] relates how he drew from Tsikinya-Chaka (‘Shake-the-Sword’) the language of his love-letters to his M’Bo bride’.

But how did Gollancz come to invite Plaatje to contribute to the volume? This had baffled me for a long time until I read Brian Willan’s excellent recent biography of Plaatje. The answer is that Plaatje was in fact in London as Gollancz was assembling the Book of Homage. He had arrived in 1914 as one of a small SANNC delegation who travelled to England in order to present the case for the African people of South Africa against the Natives’ Land Act of 1913, the first major legislation designed to limit ownership of land by black Africans, thus paving the way for what would, much further down the line, become the apartheid system. Initially the delegation was encouraged by the responses they encountered – both press and public expressed support – but the government was not inclined to listen, never mind to lobby the South African authorities to change their minds. Moreover, the delegation’s arrival in London was as unfortunately timed as could be, coinciding as it did with the outbreak of the First World War. Most of the delegation accepted that their mission was over and it was time to return home. Plaatje didn’t give up so easily, choosing to stay on, with very limited means – living hand to mouth first of all in Leyton and then in Acton – so as to write a polemical book about the Natives’ Land Act and thereby bring its implications to as wide an audience as possible.

During his time in London, Plaatje was helped by a group of friends and supporters with a longstanding interest in African politics. One of this group was Alice Werner, lecturer in African languages at King’s, a remarkably learned woman who spoke several European and African languages (she would soon move to teach at the newly formed SOAS, eventually becoming Professor of Swahili) and who was committed to the politics of African liberation. It seems to have been Werner who introduced Plaatje to Gollancz – he thanks her in his acknowledgements, though without specifying what for – and who also around this time introduced Plaatje to Daniel Jones, a UCL linguist and early pioneer of phonetics with whom in 1916 Plaatje co-authored a guide to the Tswana language. He finally returned home the following year, passing the time on the long sea journey home by translating Julius Caesar into Tswana.

Thus Sol Plaatje – now quietly revered both as a founding father of post-apartheid South Africa and, because of his epic novel Mhudi, as a major figure in South African literary history – had what you might call an honorary King’s connection early in his career. Desmond Tutu may be the best-known figure in South Africa’s liberation struggle to be associated with King’s, but he has an illustrious predecessor and one with a pleasingly direct connection to a member of the English department. You may not have noticed, but when you enter the sixth floor of the VWB, just behind the doors there is a memorial plaque to Israel Gollancz. I suggest next time you’re in the department you pause for a moment as you enter and pay your respects not only to Gollancz but also to his colleague Alice Werner and, above all, to the remarkable Solomon Plaatje, who saw in the distance the evils of what would become apartheid and devoted his life to resisting it, and who found in Shakespeare a way to express this struggle.

Here, by way of conclusion, is Plaatje’s pointed adaptation of one of Shylock’s best-known speeches (NB ‘Kaffir’ is a highly offensive term for a black African):

He hath disgraced me and laughed at my losses, mocked at my gain, scorned my nation, thwarted my bargains, cooled my friends, heated mine enemies; and what is his reason? I am a Kaffir. Hath not a Kaffir eyes? Hath not a Kaffir hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? Is he not fed with the same food, hurt by the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same summer and winter as a white Afrikaaner? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that.

[If you want to know more about Solomon Plaatje, try his 1930 novel Mhudi (Johannesburg: Penguin, 2005), which is available in the Maughan Library, and see Brian Willan, Sol Plaatje: A Life of Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje, 1876-1932 (Auckland Park: Jacana, 2018); Andrew Dickson, Worlds Elsewhere: Journeys Around Shakespeare’s Globe (London: Bodley Head/Penguin Random House, 2015); Gordon McMullan, ‘Introduction’ to reissue of Israel Gollancz (ed.), A Book of Homage to Shakespeare, 1916 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), v-xxxiii.]

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.

You may also like to read: