by Max Saunders, Professor of English; Fellow of the English Association; and Director of the Centre for Life Writing and Research.

Almost a century ago a young geneticist, J. B. S. Haldane, made a series of startling predictions in a little book called Daedalus; or, Science and the Future. Genetic modification. Wind power. The gestation of children in artificial wombs, which he called “ectogenesis.” Haldane’s ingenious book did so well that the publishers, Kegan Paul, based a whole series on the idea. They called it To-Day and To-Morrow, and between 1923 and 1931 published over 100 volumes, byrising stars like Haldane, and leading thinkers like Bertrand Russell, who answered Daedalus with a much gloomier warning about the future of science, called Icarus.

The books were highly diverse. They covered technological subjects – aviation, wireless, automation, politics, the state, the family and sexuality. Others focused on culture and everyday life topics – theatre, cinema, the press, language, clothes, food, drink, leisure, and sleep.

They got people talking. Aimed at educated readers rather than a mass market, they still had a profound impact. Winston Churchill read Daedalus and immediately wrote an essay titled ‘Shall we all Commit Suicide?’ Haldane’s friend Aldous Huxley also read it, and in Brave New World imagined a society in which ectogenesis was combined with mass production.

A publishing sensation until the Depression hit, the series attracted leading writers – Vernon Lee, Robert Graves, Vera Brittain, the scientist J. D. Bernal, Hugh MacDiarmid, critic Bonamy Dobrée, philosopher C. E. M. Joad, novelist and biographer André Maurois – and many more. Other major modernist authors knew them. Joyce read twelve of the books. T. S. Eliot reviewed some, saying: “we are able to peer into the future by means of that brilliant series of little books called To-day and To-morrow.” Virginia Woolf’s husband Leonard reviewed at least eight. Evelyn Waugh tried to write one, called Noah, or the Future of Intoxication, but it was rejected.

There were some duds. Eliot was right to be unimpressed by Pomona, Basil de Sélincourt’s waffly book on the future of the English language. He would have thought less of R. C. Trevelyan’s Thamyris; or, Is there a Future for Poetry? (He admired John Rodker’s understanding of modernism in The Future of Futurism.) Some are unsurprising. Some are mad. Tank strategist J. F. C. Fuller, in Pegasus, which sounds like it should be about flight, suggested the world would be a better place if half-track vehicles were careering about off-road, tearing up the landscape. There is some chilling eugenics, though the series also contains some of the period’s most cogent critiques of eugenics’ scientific claims. Other writers betray assumptions about class, gender, and race that make us wince now.

But, overall, this is brilliant, exuberant writing, rich with bracing ideas which can make subjects we thought we knew well look fresh and different. So why are these books not well-known?

Perhaps it’s because they elude the stereotypes of literary history. They don’t conform to the image of a generation traumatised by the war they had just been through. Here, even the writers best known for their iconic works about such trauma, Graves and Brittain, are enjoying looking ahead; being playful and witty while simultaneously writing Goodbye to All That and Testament of Youth.

They seem equally hard to square with traditional ideas of modernism. They are (of course) future-oriented, where modernists are usually perceived as placing a present seen as degraded against a classical past. To-Day and To-Morrow’s Latin or Greek titles were perhaps a bit of camouflage, or at least a provocation.

In terms of genre they are hard to place too. Hybrid, shapeshifting from essay to prediction to science fiction to future history to satire and parody, they don’t conform to more familiar modernist genres of story, novel, or poem.

Most of the writers were socially progressive: advocating women’s rights, sexual liberation, experimental redesign of relationships and families, socialism, internationalism, and anti-imperialism. As such, they were anathema to Tory modernists.

The series illuminates the inter-war period. But it can do much more. It can tell us about our time too, about how we think about the future – or don’t. One of the most striking things about reading it now is how different its visions are from today’s tomorrow. Contemporary futurology is mostly unremittingly bleak, dystopian. Certainly we should worry about climate catastrophe, antibiotic resistance, mass extinctions. But such future anxiety inhibits constructive thought about how best to avoid disaster and remake society.

To-Day and To-Morrow’s writers wanted prediction to be more scientific. The period they helped usher in transformed its methodologies. Nowadays prediction comes from multi-disciplinary teams, think tanks. Methods of scenario planning, horizon scanning, forecasting, and above all the use of machine learning to analyse data patterns, have vastly increased the accuracy of short range predictions, from weather to epidemics.

Yet the individual visionaries represented in the series have not been superseded. The long form essay allowed them greater scope than in speeches or journalism. They could elaborate their visions, take them further than more systematic methods can reach. Big data, after all, is past data. It can tell us what’s trending, and we can extrapolate those trends. Group-based futurology irons out idiosyncrasies. But it’s the individual imagination that, sometimes, can make the quantum jumps that bring the genuinely new into being. That’s what we need more of now –not to delude ourselves that we can know the future with any certainty, but to imagine futures that are worth working towards.

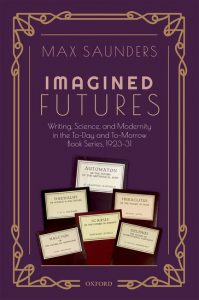

Imagined Futures: Writing, Science, and Modernity in the To-Day and To-Morrow Book Series, 1923-31is available now from Oxford University Press.

This blog is kindly reproduced from OUPblog.

Featured image credit: “Skyscrapers in China” by Maksim Samsonov. CC0 via Unsplash.

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.

You may also like to read: