by Clare Pettitt, Professor of Nineteenth Century Literature and Culture, Department of English

“Dissent clearly varies in terms of seriousness”, says Ian Hislop, the guest curator of the British Museum’s new exhibition. It certainly does. I Object: Ian Hislop’s search for dissent throws together a peculiarly Hislopian blend of public school scatological gags and objects and images that record acts of resistance under totalitarian regimes that may have resulted in the torture and/or death of their makers. The stakes are vertiginously uneven, and as a result, the exhibition frequently runs into problems of tone.

As curator, we encounter a thoughtful and knowledgeable Hislop, respectful of other cultures and alert to injustice and cruelty in the world. But as presenter, we encounter more of a fnarr fnarr chortler: “Gillray knew what would sell a print – sex, the royal family and fashionable shoes”, he chuckles, or “Have workmen on building sites always been keen on sexual commentary?” It is an interesting problem. Amnesty International meets Finbarr Saunders meets the British Museum, and the result is often confusing, but never boring.

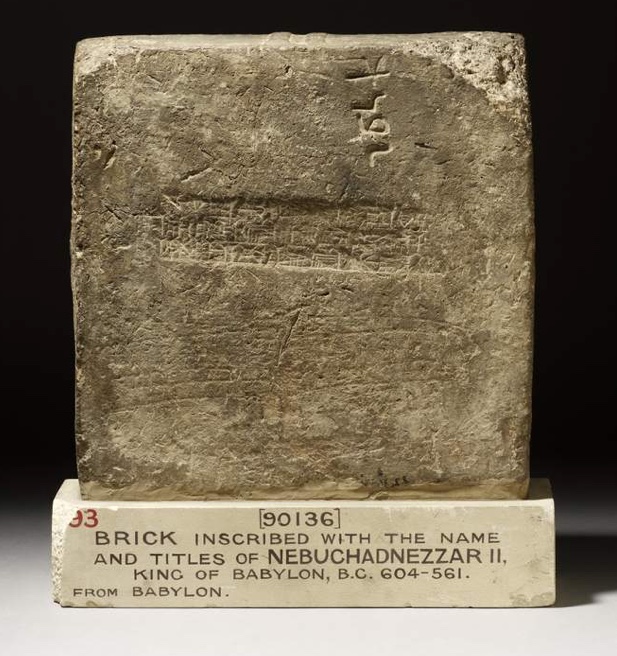

I Object is constituted exclusively of objects from the British Museum’s permanent collection ranging across huge distances and timescales, from an ancient Babylonian brick to modern Kenyan textiles: most are British only by ownership. Hislop addresses the multiple provenances of the artefacts on display by appealing to an ideal of common humanity. “There are certain basic functions that we all share: birth, copulation and death, with defecation in the middle. The other basic function is to laugh at the fact that the human condition is what it is.”

But is this an exhibition about laughter? Or about protest? The two can come together, but they do not need to.

After all, there was probably not much that was funny about producing or reading the anti-Nazi pamphlet Freiheit exhibited here. The pamphlet was distributed in 1938 concealed inside the fake covers of a suitably banal Workplace Handbook for Accident Prevention. One is reminded of Otto and Anna Quangel in Hans Fallada’s brilliant novel, Jeder stirbt für sich allein (Alone in Berlin). Fallada based it on the Gestapo file of a real-life working-class couple, Otto and Elise Hampel, who left postcards in the lobbies and staircases of public buildings around Berlin with messages in disguised script, “PASS THIS CARD ON SO THAT MANY PEOPLE READ IT! . . . .WORK AS SLOWLY AS YOU CAN! – PUT SAND IN THE MACHINES! – EVERY STROKE OF WORK NOT DONE WILL SHORTEN THE WAR!” Real, hard-core dissent against a totalitarian regime is high-risk and in 1943 both the Hampels were decapitated by the state. Not many laughs there.

Are objects rendered silent by being displayed in a museum?

Hislop’s omnipresence is what marks it as different from, for example, the Disobedient Objects exhibition at the V&A in 2014. But his objecting objects prompt similar questions, such as what can objects say, and how can an object be disobedient? Is a museum a good place to unleash their dissent, or do we ossify them and render them silent by display? Many of the objects on display here (the yellow umbrella from the Hong Kong Umbrella Movement and the Mahdi ragrobes are two examples) are not so much agents as props, and they need somehow to be set in motion or put back into performance or practice to become meaningful again.

However universal the impulse to ridicule might be, individual acts of dissent tend to be very topical, specific and ephemeral, so most of the objects in this exhibition require a lot of context. As a result, the cases and the walls are busy with text. Visual satire can speak for itself better, but there is very little of it here, which is surprising given the British Museum’s extraordinary collection of satirical prints. Hislop’s three engaging BBC Radio 4 programmes, in which we hear from a variety of scholars and practitioners, perhaps work better than the gallery space at contextualizing the objects and they are certainly worth a listen before or after a visit to the exhibition itself.

What of the museum of the future…?

A lone pink “pussyhat” worn at the Women’s March in Washington on January 21, 2017 looks a little sad and stranded under glass. Again, the object announces only its insufficiency as an explanation, so a slightly haughty museum-voiced text tells us that it was made in response to “disparaging remarks made about women by Donald Trump”. This rather understates the violence of Trump’s remark to Billy Bush about “grab[bing] them [women] by the pussy”. Here, along with the other contemporary or near-contemporary exhibits in the museum, it might have been effective to include a video or audio contribution from the protester concerned. The woman who knitted this hat and wore it on the Women’s March might have had something interesting to say about it, and I doubt she would have used the word “disparaging”.

We do hear live voices in the two Protest Playlists available for listening. Short extracts of protest songs from around the world include Fatoumata Diawara singing against female circumcision in Mali, Billie Holiday singing “Strange Fruit”, and an anti-Vietnam war song. Other than the music recordings, and two poster designs created by an art collective called ‘The Syrian People Know Their Way’ which were distributed as digital files sent via Facebook in 2012, the exhibition has very little digital content. This may reflect the British Museum’s collections policy, but it perhaps raises an interesting question about the museum of the future.

Does protest have its own rules and conformism too…?

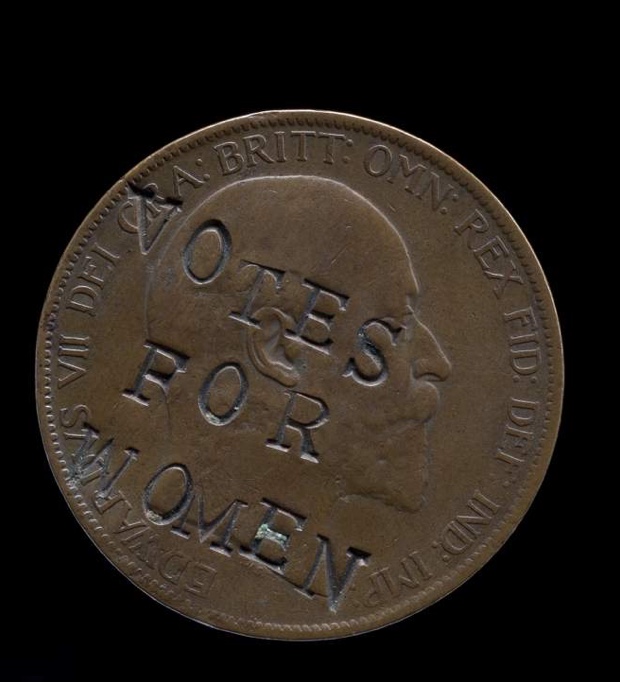

The Syrian poster designs are the only evidence of the social media phenomenon of the Arab Spring, and the theme of circulation is mainly represented in old analogue form by money. Tom Hockenhull, Ian Hislop’s co-curator, is the Curator of Modern Money at the Museum, and there are coins and notes aplenty on display, stamped with protests such as “Votes for Women” or “Stay in the EU”. As the curators point out, “defacing a coin or note has often been the most effective way of anonymously transmitting a message”.

Not all messages of protest are transmitted anonymously, and the show includes a selection of lapel badges. The dissenting badge designs that visitors to the exhibition are invited to write or draw and pin up on the wall are strikingly predictable. Most reach for ready-made slogans: “Black Lives Matter”; “No Brexit”; “Freedom for Kurds”; “Support your Sisters – Not just your Cisters”; “Abolish Student Fees”; “Properly Funded NHS”. The messages we choose to attach to our bodies when we live in a democracy are perhaps less dissenting than self-identifying. Protest has its own rules and conformism, too.

Should Ian Hislop be Prime Minister?

One message stands out as distinctive, though, “Ian Hislop should be Prime Minister”. This seems, in the current joyless circumstances, not at all a bad wheeze, but Hislop is of course already very busy doing his job as Editor of Private Eye. Having refused to go digital, the magazine is now recording its highest ever circulation, proving that dissent has always thrived in print and has perhaps faltered in finding its place in the pandemonium of Facebook and Twitter.

Private Eye is serious about its humour, and Hislop allows himself one of his own covers in the exhibition. Referring to the 2008 Zimbabwe presidential run-off, it shows a picture of Robert Mugabe announcing into a microphone “The opposition were soundly beaten”. A military officer standing next to him adds “To death”. Under Hislop, Private Eye has been tenacious in its exposure of human rights abuses in countries which have relationships with the British government. “I have spent a career operating in the realms of the written word and in my satirical field you risk no more than the odd libel writ”, Hislop says. Alas, this has not been true for, say, Charlie Hebdo.

Photograph: © The Trustees of the British Museum

Making people think is surely good and making them think twice is even better…

A label introducing a section called “Concealed Messages” tells us that “hidden messages range from sexist jokes to pro-revolutionary declarations”. Sexist jokes are surely the opposite of dissent in that they support a dominant culture. Heterogeneous to the point of chaotic, I Object dodges distinguishing satire from protest, dissent from dissidence or from Bartleby-like resistance, but then again it is easy to be po-faced and carp at the incoherence of this exhibition. It is undoubtedly a bit of a mess.

But when I was there its dense, closely packed space was teeming with truly engaged and gleeful punters. Every now and then someone would burst into loud laughter, but there were plenty of earnest conversations set in motion by the objects too. Hislop is better on satire than protest, making the modest claim that satirical objects and images “may make people think twice, and I think that’s the best anyone can hope for”. And he is right: making people think is surely good and making them think twice is even better.

The featured image is of Ian Hislop at the British Museum, where he has curated the exhibition I Object: Ian Hislop’s Search for Dissent. Photograph: © Trustees of the British Museum.

This review was originally published in the Times Literary Supplement. You can read the original review here.

You may also like to read:

John Donne and the Jacobean Fake Media

Famous Writing Desks, Southern Hospitality and Monuments to Lost Lives: King’s visits UNC

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.