by James Rakoczi, PhD researcher, Department of English

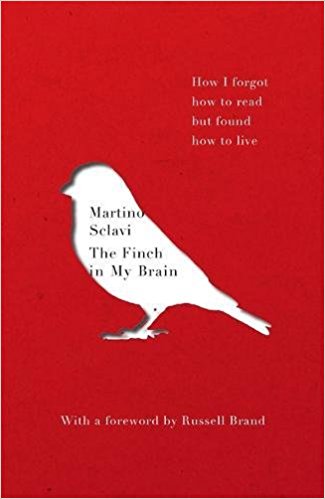

Reading Martino Sclavi’s The Finch in My Brain (Hodder & Stoughton, 2017) took longer than expected. I found myself slowing down, re-reading passages, trying to work out how the text relates to itself, to its images, and to the people in Sclavi’s life.

My copy of the text is now defaced by marginalia, doodled over in an inky green.

Page 308, for example, tells me to re-read p. 215. I turn that page, and p. 216 directs me to p. 268, and so on. My copy has gone a bit rhizome: an ecology of self-citation…

In early 2011, living in LA, Italian film producer Martino Sclavi was experiencing bad headaches. He thought it was the coffee, or the stresses of script-writing to deadline. In fact, it was a grade 4 glioblastoma – an extremely severe brain tumour. During a script-reading, Sclavi became increasingly delirious. Driven to a hospital by a friend, Sclavi recalls how his friend’s words ‘stopped having a meaning for me… just sound with no information. A rhythm with no shape’ (p. 43). This loss of ‘meaning’ but retention of ‘shape’ characterised not only Sclavi’s immediate crisis but presaged the direction his life would take.

Sclavi benefitted from much medical expertise in his treatment. His first surgeon, Dr Vogel, operated on Sclavi skilfully, cutting out a large chunk of the tumour. ‘With no Vogel,’ acknowledges Sclavi, ‘there would be no story’ (p. 18). He was enrolled – freely – into a cutting-edge treatment programme in the USA. Then, in Italy, he joined a series of innovative healthcare programmes. This included, most viscerally, an operation in which the remaining tumour was cut out of Sclavi’s brain – whilst Sclavi remained awake. If Dr Vogel made the story possible, it is this second surgery that makes this story be told the way it is. For after this surgery, Martino Sclavi lost the ability to understand text.

The Finch in My Brain is a book that the writer can never read.

Because of this, Sclavi uses a software program he calls Alex. Sclavi writes by typing, but he forgets what he’s writing as he types and cannot read what he writes. So Alex reads back – in a monotone, robotic voice – everything in Sclavi’s word processor. Alex ‘makes every detail of this book possible, but at the same time he flattens every single word’ (p. 216). Alex also becomes a friend for Sclavi’s increasingly isolated existence. On one page, for example, Sclavi has a warm-hearted argument with Alex about whether he meant bagels or beagles (he meant bagels). Alex turns the text into an impressively immediate text: typos become part of its literary strutcure [sic].

Martino’s estranged wife Margarita interjects with several footnotes throughout the text. These footnotes complicate the text geometrically. They push Sclavi and Alex’s text across the page and spatialize what Martino and Alex write. We become plagued by the possibility that the text’s “Martino” is an unsettled, changing thing – a morphological entity rather than a coherent subject. ‘Even If I was finally there, next to you, emotionally you were somewhere else’ (p. 10), writes Margarita.

This is a unique way of rendering the instability of the subject – and I was moved by Sclavi’s honesty in including them. I wanted to read more from Sclavi’s estranged wife Margarita.

The Finch also incorporates a series of chapters, written in Optima font, where Martino talks about his life before diagnosis (from 2000-2010). He tells us that he enjoys writing these chapters because he has ‘a much easier time recalling my more ancient history’ (p. 49). This method of interweaving an autobiography of one’s life into every other chapter has become something of a generic convention for published illness narrative. It is interesting to learn about Sclavi’s role in the rise of Russell Brand’s career (including Brand’s struggles with addiction) as well as his adventures with Hungarian director Béla Tarr.

Nevertheless, it is in the book’s final third, when the story of Martino’s ‘ancient history’ reaches the present and these chapters of the past fall away that The Finch becomes – for me – an altogether more unusual, troubling and experimental book. From then on, the text attempts to live in the present tense. Martino writes his life as he experiences it, as he survives it, and as he philosophises/poeticises it. From this point, too, the challenges of this review crystallised for me.

How would you approach – let alone, judge – a memoir told by a man with a hole in his head, a hole which influences what that text is like?

We could assess the text’s merits by its own self-avowed intentions to transform Sclavi’s condition into ‘a source for a new vision’ (p. 269), to touch and share something ‘meaningful’ (p. 232). Or, we could recognise the text as a personal therapeutic strategy, the way writing has ‘always been’ Sclavi’s ‘path of self-therapy’ (p. 178). Maybe we could turn this review into a piece of qualitative health research. Did Sclavi recover? Did the text play a role in his recovery? What would it mean to suggest it did? (Sclavi himself says that such matters of health ‘can’t be studied’.

Or, perhaps we could listen. In the spirit of a Samaritan call-volunteer sometimes the thing to do is to be there, to attend to the words of another without trying to influence the way those words sound…

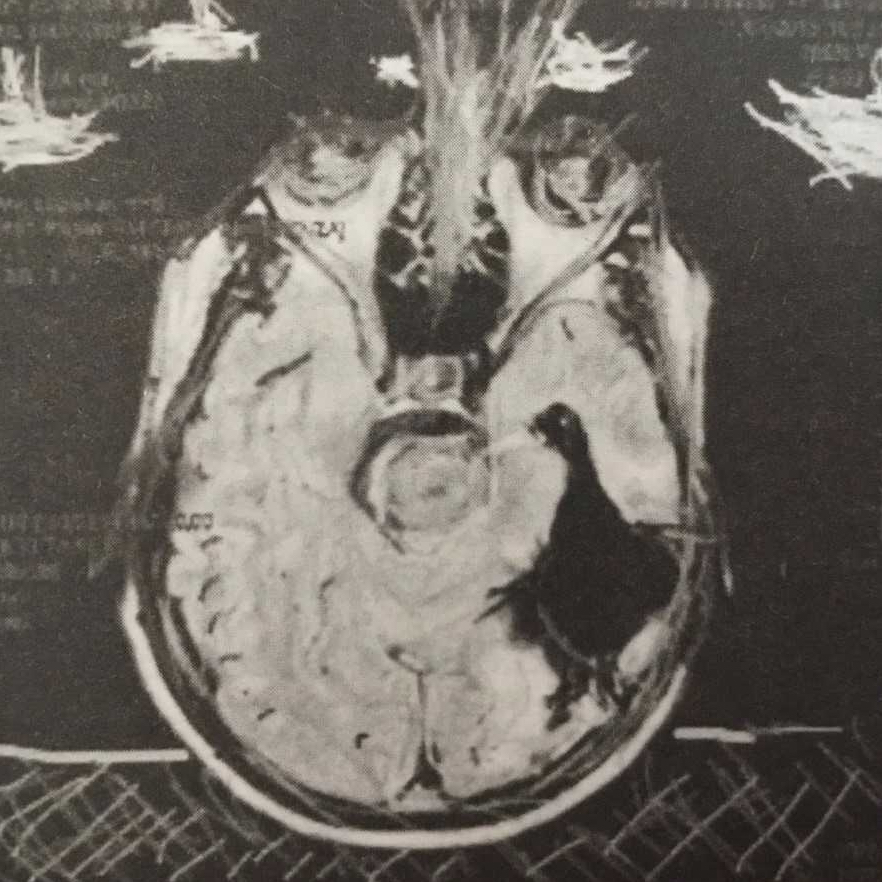

The eponymous finch is from the shape of the hole in Martino’s head. The formlessness of a hole takes on shape. The wordlessness of a writer produces a book. The book has flaws. It fails to explore properly the economic privilege of Martino’s healthcare. It recognises the importance of intersubjectivity but remains unable, I think, to concretise this importance. I am also unsure whether the therapeutic strategies it embraces are sound—certainly, they are not politically neutral. But through these flaws, a defiant account of surviving emerges. Listen. We will hear Sclavi tell a story of how wordlessness speaks.

Featured image illustration: Eleanor Shakespeare/based on a portrait by Massimo Scognamiglio, © The Guardian

You may also like to read

The Long Read: Arabic Illness Narratives and National Politics

Book Review: Literature and the Public Good

Book Review: Thinking in Cases

Confessions of a Medical Humanist

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.