by Diya Gupta, PhD researcher, Department of English

Two-and-a-half million men from undivided India served the British during the Second World War. Their experiences are little remembered today, neither in the UK where a Eurocentric memory of the war dominates, nor in South Asia, which privileges nationalist histories of independence from the British Empire. And yet military censorship reports from the Second World War, archived at the British Library’s India Office Records and containing extracts from Indian soldiers’ letters home, bear witness to this counter-narrative. What was it like fighting for the British at a time when the struggle for India’s freedom from British rule was at its most incendiary?

Extracts from these letters, exchanged between the Indian home front and international battlefronts during the Second World War, become textual connectors linking the farthest corners of the Empire and imperial strongholds requiring defence against the Axis alliance. Such letters map the breadth of a global war and plunge deep into the Indian soldier’s psyche, revealing ruptures in the colonial identity foisted on him.

“Whenever I sit for my meals, a dreadful picture of the appalling Indian food problem passes through my mind leaving a cloudy sediment on the walls of my heart which makes me nauseous and often I leave my meals untouched.”

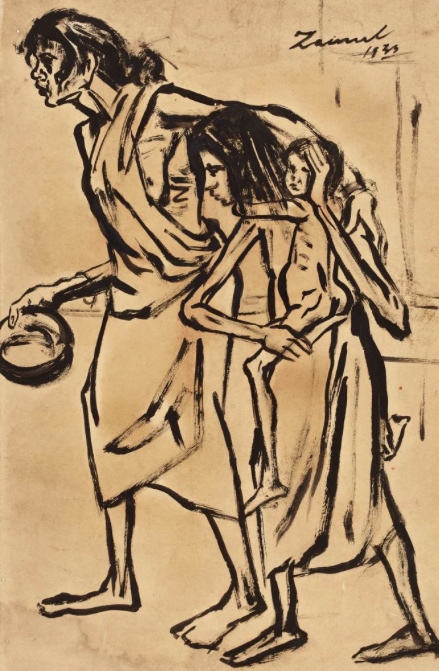

Food dominates much of these epistolary conversations, with Indian soldiers reflecting on their army rations and diet abroad. Rumours of a great and devastating famine sweeping India, and particularly Bengal, in 1943 reach them, despite censorship of news and letters. A Havildar or junior officer, part of the Sappers and Miners unit, writes from the Middle East: “From my personal experience I can tell you that the food we get here is much better than that we soldiers get in India. But whenever I sit for my meals, a dreadful picture of the appalling Indian food problem passes through my mind leaving a cloudy sediment on the walls of my heart which makes me nauseous and often I leave my meals untouched.”

The soldier highlights his solidarity with this imagined community of sufferers through images of his own body, and his reactions are expressed in physiological terms – he visualises the walls of his heart being covered with ‘cloudy sediment’ at the thought of food shortage in India. In visceral terms, this is how he understands empathy. The spectre of famine in India hovers, Banquo-like, before him every time he sits down to eat his rations carefully provided by the colonial British government; the projection of food deprivation in his homeland thousands of miles away reaches out and, almost literally, touches his heart, preventing him from eating.

The spectre of famine in India hovers, Banquo-like, before him every time he sits down to eat his rations carefully provided by the colonial British government…

Another letter from a Havildar Clerk to relatives in South India relates the helplessness caused by famine to the extraordinary conditions of the wartime marketplace: “I am terribly sorry to learn about the food situation in India and it seems as if there is no salvation for me. From my earliest days to the present time I have always been in this abyss of misery. It was with grim determination to see you all free from poverty that I allotted my whole pay of Rs 85/- to you, but cruel Fate is determined to defeat me in all my purposes. What is the use of money when we are unable to obtain the necessities of life in exchange for it? The situation would drive even the most level-headed of us to madness and when we think of conditions in India we become crazy as lunatics.”

“When we think of conditions in India we become crazy as lunatics.”

How can the soldier’s earnings help his family when ordinary people have been priced out of food because of soaring rates of wartime inflation? The letter reveals both the economic bonds linking the Indian soldier’s participation in an imperial war, and the psychological despair of being unable to rescue loved ones from hardship – as traumatic for the soldier as the heavy fighting he witnesses on the battlefield.

__________________________________________________________________________

This blog post was first published by the British Library’s ‘Untold Lives’ series. Read the original post here.

Find out more in this short King’s film.

__________________________________________________________________________

You may also like to read Loving, Living and Resisting: A Postcolonial Conversation and South Asians and the First World War: Reflections.

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and not those of the English Department, nor King’s College London.