Featured image: Living With AIDS (1987-1999), Gay Men’s Health Crisis records, Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library.

by Dan Udy, LAHP/ AHRC PhD researcher working on “Going Viral: Queer (Re)Mediations in the YouTube Decade”

When Sarah Schulman and Jim Hubbard began filming interviews for the ACT UP Oral History Project in 2002, the history of HIV/AIDS activism was largely consigned to videotape. Having aligned with the emergence of handheld camcorders, it was the first political movement to be documented on video and from within its ranks: amateur recordings, artist tapes, and independent TV productions all formed a staggering cultural archive that tracked how marginalized communities took healthcare, research, and advocacy into their own hands during the early years of the HIV/AIDS crisis.

For over 20 years these tapes were consigned to personal collections and institutional archives such as the New York Public Library (NYPL), where the Manuscripts and Archives Division holds the most extensive public collection of such videos in the world. Here, facsimiles of original tapes could be watched on monitors, but the analogue nature of these materials made it difficult to circulate them beyond the library’s walls.

Over the past decade, though, early HIV/AIDS activism and the video records it left behind have crept back into public view. High-profile documentaries such as How to Survive a Plague (dir. David France, 2011) and United in Anger: A History of ACT UP (dir. Jim Hubbard, 2012) have re-used archival footage, and exhibitions including the NYPL’s own Why We Fight: Remembering AIDS Activism (2013) have displayed video and ephemera from the same period. More broadly, the advent of video streaming in the mid-2000s enabled previously unseen tapes of ACT UP protests [cn: video shows death statistics, and human ashes being scattered] and television recordings to be digitized and shared online. As amateur archivists began to upload these videos to sites such as YouTube, institutional archives gradually followed suit.

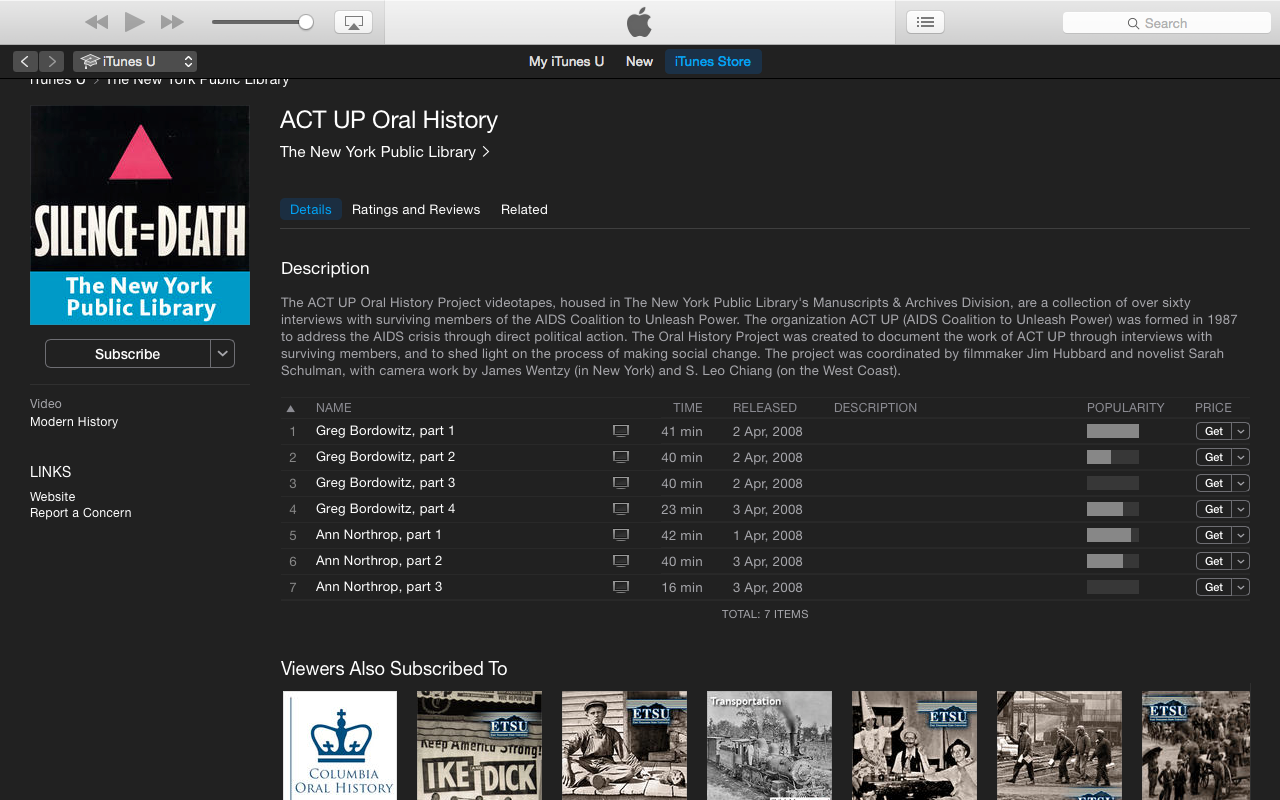

In 2012 the NYPL began the process of digitizing videos from their AIDS activist collections after receiving a large donation, and at the time of writing are mid-way through the project. Although only a small number of files have been circulated online – including two ACT UP Oral History Project interviews, available for free download from the iTunes store – watching digitized tapes in the Manuscripts and Archives Division has transformed the way in which researchers can use the library’s collections, and has produced new types of collaboration amongst scholars, activists, and archivists.

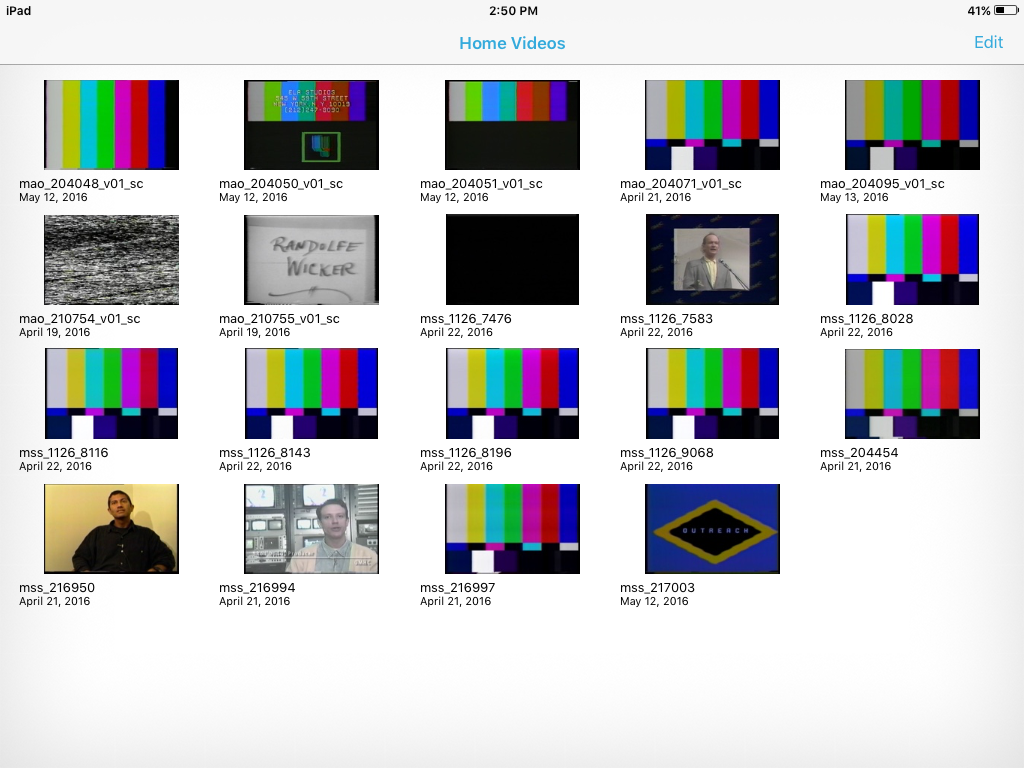

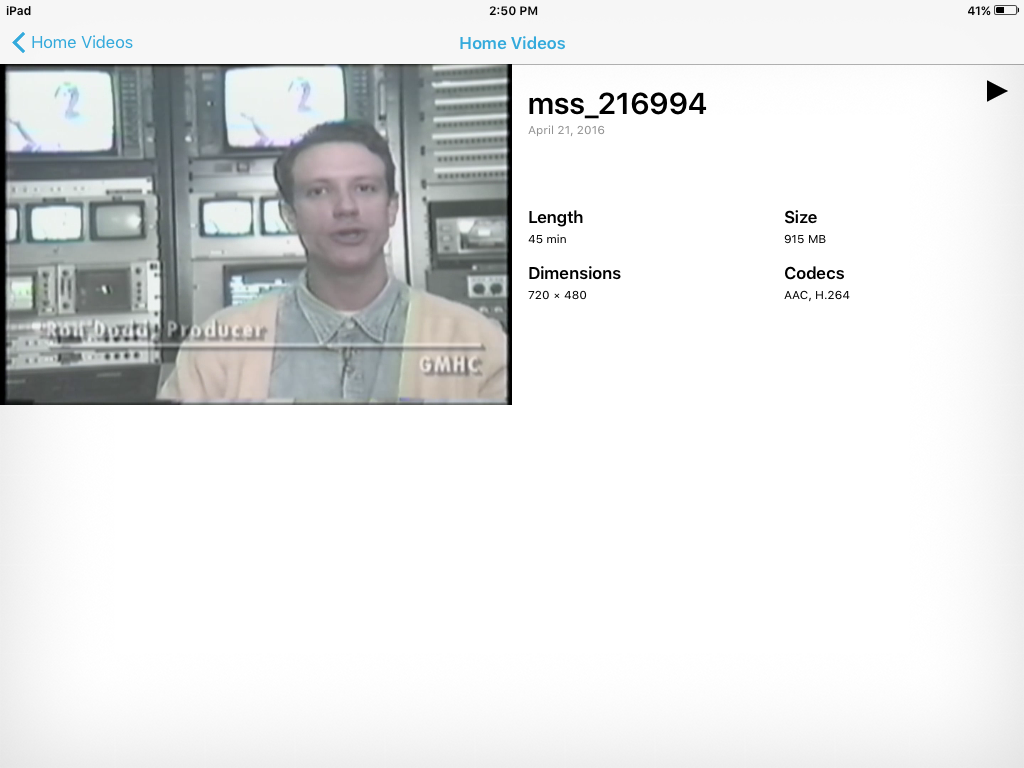

As part of a recent research trip for my PhD project, I spent many days in the Manuscripts and Archives Division Reading Room watching videotapes and TV productions produced by the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC). Unlike their analogue counterparts, these digital files were uploaded from a central database onto a NYPL iPad. Switching between different videos now takes a matter of seconds, users can scroll to specific points in each file and, crucially, video stills can be taken with the iPad’s screenshot function.

The latter has revolutionized how researchers such as myself are able to work with these media archives, and allowed me to easily capture and share images with fellow scholars and the general public. Being able to circulate screenshots so easily also led to virtual collaborations with those that featured in them: where gaps existed in the archive listing I could send images to surviving activists to find out who it was on screen and when the tapes were filmed, and then feed this information back to NYPL archivists to help update the library’s records.

As a result, the process of archival research quickly changed from a solitary practice into a collective, communal one. The digitized collections opened up new possibilities for intergenerational queer connection, and helped illuminate how the legacies of the past might function in the present. Mediating between a physical archive and an ever-expanding virtual one showed me how established ways of doing scholarship – of working with archives, of interviewing subjects, and of sharing your research – are being revolutionized by new technologies, and pointed to the exciting opportunities the NYPL archives hold for future activists and scholars.

What I didn’t expect, though, was the affective weight carried by the full-length tapes…

When working in digital media studies, it’s easy to assume that a laptop and WiFi connection are all the research tools you need. I’d seen short clips of many videos online, and thought that working at the NYPL would simply flesh out some missing details and give me an extra footnote or two. What I didn’t expect, though, was the affective weight carried by the full-length tapes; while I still believe that physical archives hold many problems – namely that they restrict knowledge access to those with time, money, and university ID – I certainly won’t forget crying into an iPad while my neighbour thumbed through old manuscripts any time soon.

Further links:

- Visual AIDS – artist driven activism

- Postervirus – annual poster series run by AIDS Action Now

- What Would an HIV Doula Do? – records of a cross-community workshop and conference of the same name

You might also like to read ‘A New Route Discovered: On Shakespeare’s Sonnets’

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and not those of the English Department, nor King’s College London.