by Carl Kears, lecturer in Old and Middle English literature before 1400 at King’s College London, and James Paz, University of Manchester and King’s alumnus.

Science fiction may seem resolutely modern, but the genre could actually be considered hundreds of years old. There are the alien green “children of Woolpit”, who appeared in 12th-century Suffolk and were reported to have spoken a language no one could understand. There’s also the story of Eilmer the 11th-century monk, who constructed a pair of wings and flew from the top of Malmesbury Abbey. And there’s the Voynich Manuscript, a 15th-century book written in an unknowable script, full of illustrations of otherworldly plants and surreal landscapes.

These are just some of the science fictions to be discovered within the literatures and cultures of the Middle Ages. There are also tales to be found of robots entertaining royal courts, communities speculating about utopian or dystopian futures, and literary maps measuring and exploring the outer reaches of time and space.

The influence of the genre we call “fantasy”, which often looks back to the medieval past in order to escape a techno-scientific future, means that the Middle Ages have rarely been associated with science fiction. But, as we have found, peering into the complex history of the genre, while also examining the scientific achievements of the medieval period, reveals that things are not quite what they seem.

Origins

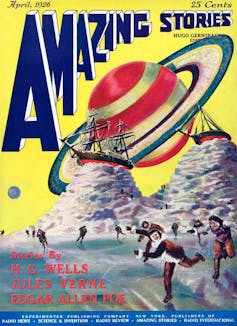

Science fiction is particularly troublesome when it comes to matters of classification and origin. Indeed, there remains no agreed-upon definition of the genre. A variety of commentators have located the beginnings of SF in the early-20th-century explosion of pulp magazines, and in the work of Hugo Gernsback (1884-1967), who proposed the term “scientifiction” when editing and publishing the first issue of Amazing Stories, in 1926.

“By ‘scientifiction’,” Gernsback wrote, “I mean the Jules Verne, H G Wells and Edgar Allan Poe type of story – a charming romance intermingled with scientific fact and prophetic vision … Not only do these amazing tales make tremendously interesting reading – they are always instructive.”

But here Gernsback was already looking backwards in time to earlier writers to define SF. His “definition”, too, was one that could also be applied to literary creations from much further into the past.

Science and fiction

Another longstanding idea is that the “science” in science fiction is key: SF can only begin, many historians of the genre proclaim, following the birth of modern science.

Alongside histories of SF, histories of science have long avoided the medieval period (over a thousand years in which, presumably, nothing happened). Yet the Middle Ages was no dark, static, ignorant time of magic and superstition, nor was it an aberration in the neat progression from enlightened ancients to our modern age. It was actually a time of enormous advances in science and technology.

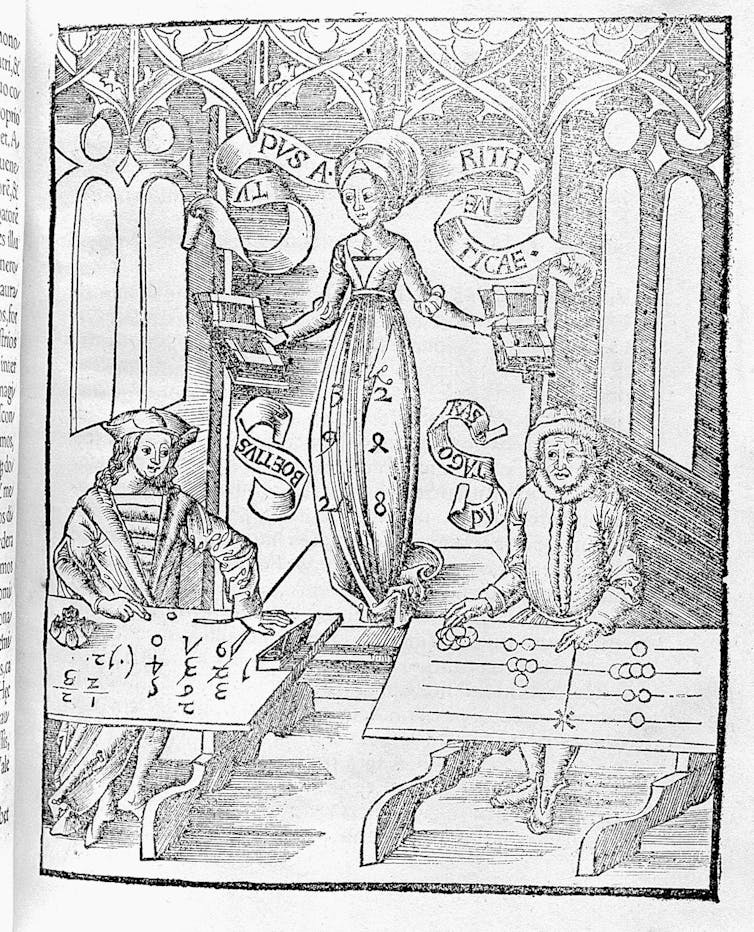

The compass and gunpowder were developed and improved upon, and spectacles, the mechanical clock and blast furnace were invented. The period also laid the foundations for modern science through founding universities, advanced the scientific learning of the classical world, and helped focus natural philosophy on the physics of creation. The medieval science of “computus”, for instance, was a complex measuring of time and space.

Like those of more modern science fictions, medieval writers tempered this sense of wonder with scepticism and rational inquiry. Geoffrey Chaucer describes the procedures and instruments of alchemy (an early form of chemistry) in such precise terms that it is tempting to think that the author must have had some experience of the practice. Yet his Canon’s Yeoman’s Tale also displays a lively distrust of fraudulent alchemists, sending up their pseudo-science while imagining and dramatising its harmful effects in the world.

The medieval future

Modern science fiction has dreamt up many worlds based on the Middle Ages, using it as a place to be revisited, as a space beyond earth, or as an alternate or future history. The representation of the medieval past is not always simplistic, nor always confined to “back then”.

William M Miller’s immensely detailed medieval future in A Canticle of Leibowitz (1959), for instance, dwells on the way the past consistently reemerges in the fragments, materials and conflicts of a distant future. Connie Willis’s Doomsday Book (1992), meanwhile, follows a time-travelling researcher of the near-future back to a medieval Oxford in the grip of the Black Death.

Although “medieval science fiction” may sound like an impossible fantasy, it’s a concept that can encourage us to ask new questions about an often-overlooked period of literary and scientific history. Who knows? The many wonders, cosmologies and technologies of the Middle Ages may have an important part to play in a future yet to come.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Featured image: Comet in the sky, 1340. Wellcome Collection, CC BY-SA

You may also like to read:

Founders of England? Tracing Anglo-Saxon myths in Kent, by Fran Allfrey and Bethany Whalley

A Day in the Life of the Humanities, by Alan Read, Lizzie Eger, Rowan Boyson, Josh Davies, Clare Lees, and Ruth Padel

The Long Read: Arabic Illness Narratives and National Politics, by Faten Hussein and Neil Vickers

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.