By Rachael Nicholas, PhD candidate (University of Roehampton), MOOC mentor, and alumna of the King’s MA in Shakespeare Studies

In case you’d missed it, 2016 marks the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death. Whilst some of the celebrations have commemorated the man himself, the catalogue of performances and special events comprised a celebration of afterlives, focusing on the 400 year history of encountering Shakespeare and his works. Their sheer range is a testament to the part that adaptation across different media has played in the construction of what we understand as ‘Shakespeare’ today.

The proliferation of media technologies has not only given rise to new modes of adaptation, but also to new ways of distributing and accessing Shakespeare’s work. It is now possible to open out live performances to audiences around the world through live broadcasts to cinemas, and increasingly, for free online. The question of what it means to encounter performances of Shakespeare through the digital – for both production and reception – is central to my own research project on live relay audiences. But to encounter Shakespeare through ‘performance’ is of course not the only way to encounter Shakespeare.

Reading a play, watching Sons of Anarchy on Netflix, posting a love letter on “Juliet’s Wall” in Verona, sharing a Shakespeare-themed meme or retweeting Shakespeare himself… opportunities for encountering Shakespeare abound, shaping our individual and collective sense of Shakespeare’s cultural value and meaning.

These narratives and histories of encountering Shakespeare are often personal, bound up in our own social histories. Whether we first encountered Shakespeare in a classroom, on television, or in a theatre is dependent on variables such as class, economics, schooling, and geography, and can have a lasting effect on how we continue to engage with the plays. I know how significant the DVD clips of Hamlet shown in my English A-Level classroom were in shaping my interest in Shakespeare film adaptations, and I doubt I would have kindled much of an interest in theatre at all had I not had access to the live theatre broadcasts at my local cinema.

I doubt I’d have kindled an interest in theatre at all without live broadcasts at my local cinema…

In turn, these encounters shape not only a general collective understanding, but also more practically, who ends up talking about and teaching Shakespeare. New mediums and distribution methods can have a fundamental impact on the voices that are heard in Shakespeare scholarship, as well as on what those voices are saying.

Much like live performances, the places for learning about Shakespeare have traditionally only been available to those who can be physically present in universities, classrooms or lecture theatres. But online learning in the form of Mass Open Online Courses (MOOCs), such as King’s upcoming FutureLearn course ‘Shakespeare: Print and Performance’, make knowledge available to a large number of people across space and time, who can take part in the course remotely, at their own pace, and for free.

MOOCs make knowledge available to people across space and time, who take part at their own pace, for free.

Starting next week in collaboration with the British Library and Shakespeare’s Globe, this King’s course digitally opens up these institutions for learners to explore the ways in which the histories of print and performance from the early modern period to today have shaped the construction of Shakespeare as a global icon.

But what kind of encounter does participating in a Shakespeare MOOC constitute? In many ways the MOOC attempts to replicate and enhance the conditions of a physical classroom in a digital space. Despite the fact that learners can work through the content at their own pace, simultaneity is created by releasing content weekly, contributing to the sense of liveness that engages learners across the four weeks. Through ‘social learning’, learners are encouraged to comment on discussion points, interacting and sharing knowledge with each other. With recorded and non-live elements, ‘liveness’ in this learning environment is constructed and felt at the moment of participation, valued by learners and keeping them engaged throughout the course.

How do learners stay engaged with no financial investment in the course?

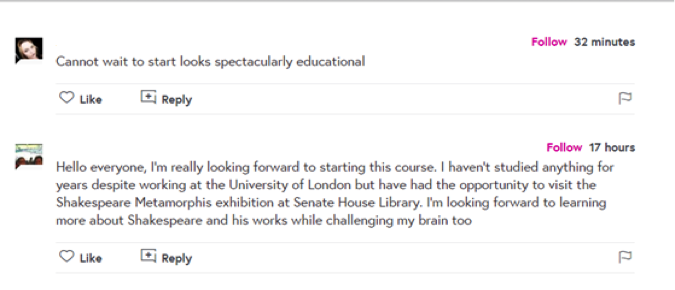

How and why do learners stay engaged, despite not having any financial or time investments in the course? Before the course has even begun, over 400 people have already signed up and shared some of their stories, referencing school experiences, films they have seen and performances they were at.

This kind of personal reflection is something we are not often encouraged to consider as part of traditional Shakespeare education, but seems to come quite naturally to those participating online. The motivations to participate are sometimes practical – supplementing undergraduate courses on Shakespeare for example, but they are often less tangible – self-improvement, increasing self-confidence, or just for pure enjoyment.

My section of the MOOC in week one focusses on personal encounters, preconceptions and approaches. When we are considering the construction of Shakespeare as a global icon today, these individual stories and the larger narrative they form may be as valuable as what we learn from print and performance histories.

Encountering Shakespeare through the MOOC will become part of the participants’ own Shakespeare stories, changing their connection to Shakespeare’s work and their identities in relation to it. The MOOC provides an opportunity for large numbers of people from around the world to access some of the world-class research and teaching at King’s. But it also offers these people a chance to share their own knowledge, and a rare opportunity for Shakespeare scholars and researchers to listen.

‘Shakespeare: Print and Performance’ begins on the 5th September 2016. You can find out more and sign up here.

Find Rachael on Twitter @Rachienix

The feature image shows letters posted on “Juliet’s Wall” in Verona. Photo via CreativeCommons.

You might also like to read ‘A New Route Discovered: On Shakespeare’s Sonnets’

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and not those of the English Department, nor King’s College London.