To celebrate the English Department’s acquisition of Val Wilmer’s portrait of Ronald Moody, Luke Roberts reflects on the life and work of the Jamaican sculptor and KCL alumnus.

For us history was the carrier of no absolutes and conformed to no overarching scriptural commandments. Nothing was ever codified as having its correct place and time. In a suitably paradoxical formulation, displacement moved to the centre.

– Stuart Hall[1]

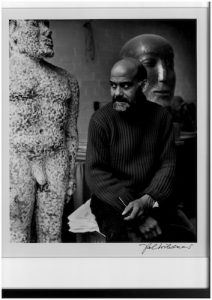

In Val Wilmer’s portrait of Ronald Moody the artist sits framed by two sculptures: the carved wooden head Tacet (1938) and the concrete and fibreglass figure The Man (1958). He holds a pipe in his left hand, gently resting on his right. His eyes are fixed on something out of shot. Although nothing in this picture returns our gaze, everything holds it. It’s a study of texture and material, balance and weight: the heavy fabric of his sweater, the flesh of the hands and the human face, the greying beard, the exposed brickwork of the studio wall, the concrete phallus, the dome of the skull, triangles of newspaper and just-visible handkerchief, light moving in and out of darkness. Moody himself is the centre of gravity, but it’s a restless centre.

Outside the studio it’s 1963, and Moody is beginning his involvement with a younger generation of writers, intellectuals and activists who come to be known as the Caribbean Artists Movement (CAM).[2] He’s recently been commissioned to make his sculpture Savacou, a ten-foot high aluminium statue of the mythological bird, controller of thunder and wind, who later transformed into a star. This sculpture, still standing at the University of the West Indies, would give its name to the CAM journal, edited by Kamau Brathwaite, and to the UWI Press. Among the younger artists he provided mentorship and encouragement to Errol Lloyd and the Nigerian-born Uzo Egonu. In 1966 he exhibited at the major World Festival of Black Arts in Dakar, and was on the selection committee for the second Festival in Lagos in 1977. For Stuart Hall he was the ‘pioneer figure’, a bridge and link to the pre-Windrush sensibility of the black diaspora in Britain.[3]

But if Ronald Moody was ahead of his time, he was also of his time, and started out aspiring to transcend time completely. Inspired by formative readings of esoteric mystics like Gurdjieff and P.D. Ouspensky, he consistently stressed a commitment to what he called ‘the recognition of eternal laws.’[4] Moody believed that artists should express the unchanging spiritual state of things, order and harmony, rising above the transient conflicts of the day. His sculptures, brooding and serene, seem to dramatize this struggle. The viewer registers the uncanny confrontation between the age of the wood and the duration of the carving, the insistence on human form beside the aura of myth. Even his birthdate is the cause of some confusion, variously given as 1890, 1910, 1901 and 1900. It’s the last that is correct and I think most fitting. When he died in 1984—‘scandalously neglected by the British establishment’, as Wilmer writes in her extraordinary autobiography—Moody was as old as the century.[5]

Born to a prominent Jamaican family—his brother was the anti-racist campaigner Harold Moody, President of the League of Coloured Peoples—Moody came to England in the 1920s to study dentistry at King’s College London Dental Hospital. Little is known about his life as a student, but a folder of poems in his archive shows him fluent in the colonial-era English curriculum. There are dentistry-themed pastiches of Milton, Herrick, Wordsworth and Byron, written for the college magazine. He took up sculpting after a revelatory visit to the British Museum’s collection of Egyptian artefacts. Working at night in his cramped and leaking greenhouse studio, Moody experimented with the dentist’s materials of putty and modelling clay before settling on wood. His breakthrough came with Wohin (1934), a head carved in oak. The title of the piece, borrowed from a Schubert lieder, should indicate the cultural syncretism that guided all of Moody’s work. As he told the West Indian Gazette in 1961:

Why am I a sculptor? I have never given myself a satisfactory answer. One does not choose a way of life—and with me it is a way of life—one grows into it; a subtle process of the interaction of past and present. My past is a mixture of African, Asian, and European influences, and, as I have lived many years in Europe, my present is the result of the friction of Europe with my past. This has not resulted in my becoming an ersatz European, but has shown what is valuable in my inheritance, which I think shows in my work.[6]

Moody’s use of ‘friction’, whether intentional or not, gestures towards his sculptural involvement with wood. I think of him sanding and oiling his carvings to their deep smooth surfaces, and how for Moody there is no singular origin for creativity. He was as much interested in the Zemi carvings of the indigenous Arawak people as he was in Confucianism.

Yet his first exhibition at the Adams Gallery in Pall Mall in 1935 shows how Moody was initially framed. Though there’s some suggestion that the exhibition was organised by the League of Coloured Peoples, the driving force were colonial administrators from the faculty at Achimota College in modern-day Ghana.[7] The show, titled ‘Negro Art’, was organised around ‘ethnological specimens’ of African art, lent by a number of English museums. These were juxtaposed with paintings by ‘contemporary English artists whose works have been inspired by an interest in negro life or art’, and work by a smaller group of contemporary black painters and sculptors. The English artists included the surrealists Eileen Agar and John Banting, as well as prominent Bloomsbury painters like the Ukrainian-born Bernard Meninsky. Alongside Moody—the only representative of the Caribbean—was the Senegalese painter Kalifala Sidibé, who had exhibited in Paris, collected by Le Corbusier and reviewed by Michel Leiris.

For The Sunday Times art critic Frank Rutter—staunch supporter of the suffragettes and champion of ‘progressive’ art—the exhibition provoked a barrage of racist reaction. Writing of the African art section he declared: ‘Even the best of them, insidiously attractive, takes us down to the animal—never up among the angels […] There is time for us all to become savages.’ Meanwhile, ‘of the European contribution it may be said without hesitation that the best show no trace of negroid elements in their style.’ He makes no mention of Moody or Sidibé.[8]

The modernist vogue for African art frequently reduced living black artists into yet more ‘specimens’ for predominantly white artists and audiences. Moody’s younger contemporary, the Guyanese painter Aubrey Williams, recalls a painful meeting with Picasso:

I remember the first comment he made when we met. He said I had a very fine African head and he would like me to pose for him. I felt terrible. In spite of the fact that I was introduced to him as an artist, he did not think of me as another artist. He thought of me only as something he could use for his work.[9]

Though the ‘Negro Art’ exhibition of 1935 was an admirably enlightened attempt at pluralist dialogue, in the curatorial methodology only the ‘contemporary English artists’ are presented as making conscious aesthetic decisions. They have chosen a limited affiliation with black art. The black artists meanwhile are subsumed under the category of Primitivism, a reductive classification it would take decades of activism to undo.

Yet under this ambivalent sign, Moody began to show his work in France and Holland to appreciative audiences and collectors. With his wife Helene he moved to Paris in 1938 and contributed to the major exhibition Contemporary Negro Art at the Baltimore Museum of Art the following year. But just as he was beginning to consolidate his reputation the Second World War broke out. After the Nazi invasion of France, he and Helene fled for Marseilles, escaping the occupying army. Moody’s letters recall walking through stretches of French countryside on bloody feet and burying their passports to evade paper inspections. As a British citizen and a woman Helene was repatriated, but Moody as a military-age male had to make a more dangerous escape from a holding camp, getting back to Britain late in 1941. He developed pleurisy and contracted tuberculosis, and after the war spent several years in a sanatorium.

While his health slowly recovered, Moody dedicated himself to other forms of artistic engagement. He wrote short stories, worked on poems he’d drafted while fleeing France, and made a series of broadcasts for Calling the West Indies, developed by Una Marson for the BBC World Service in the 1940s. His programmes reflect his range of interest: Egyptian, Greek, Indian, Chinese, Gothic, Renaissance, and Modern Art, alongside an incisive critique titled ‘What is Called Primitive Art’, and talks on exhibitions by Jacob Epstein and an overview of Mexican art at the Tate in 1953. In the transcript of a broadcast from the same year titled ‘An Exile Looks Back’, he wrote of his hopes for the future:

If, however, you will allow an exile two wishes for his homeland, I would first like to see a greater sense of unity among my fellow men; that is, a greater feeling of being West Indians, for in this will lie the future strength of the islands. But I do not want the local customs and self-sufficiency of each island to be submerged in this idea. In England, Scotch, Welsh, and English live together, and are jealous of their local customs, but in times of stress all is forgotten and they pull together. My second wish is for a speedy and orderly attainment of self-government with economic safeguards, as such responsibilities will be a great stabilising factor.[10]

Moody’s hopes would be fulfilled and dashed by the fraught years of the West Indies Federation, and the massive economic turmoil Jamaica was subject to throughout the next two decades.

He returned in earnest to sculpture in the mid-1950s, experimenting with concrete as an alternative to the more physically demanding process of carving wood. Although this change in material was practical, it also coincides with a shift in Moody’s political engagement. While his brother’s work in the League of Coloured Peoples must have brought Ronald into the sometimes-fractious orbit of activists including C.L.R. James and Jomo Kenyatta, his commitment to art placed him at an oblique. But as Independence in the West Indies became inevitable, and as he started to socialise with a younger generation of activists, his ‘friction’ with Europe rises to the surface of his work. The concrete figures are densely textured with a rough finish. Far from his pre-war mysticism, in his broadcasts to the Caribbean he makes concrete, if modest, demands.

Although his sculptures may look and feel imposing and monumental, they were also fragile objects. Moody worked without gallery representation, firmly outside the artworld, and while this gave him independence, it also left him vulnerable, under-resourced, and precarious. The Man, belonging to a larger group called Concrete Family, was apparently destroyed while being removed from his studio. Two companion pieces, The Mother and The Youth are in the collection of the Leicester Art Galleries, while another, Little Man, is now lost.[11] Cynthia Moody, the artist’s late niece and his great champion, went to heroic efforts to track down other sculptures lost during WWII in American galleries, including Midonz, his first masterpiece.[12] Before her death in 2013 she began work on a catalogue raisonné, but a monographic treatment of Moody’s oeuvre is still overdue. Even a cursory look at the archives turns up endless surprises: while we know Moody as a sculptor, as I’ve indicated he was also an entertaining and informative writer. More intriguingly, he also made ink paintings in the 1960s and 1970s, which were exhibited in Brighton in 1969, and suggest a late investigation of abstraction.

While the artist has his own complex history and formation, which I’ve only sketched here, each artwork also has its own story, and makes its own journeys and accumulates contexts and meaning. I like especially to think of The Mother in Dakar in 1966, at Leopold Senghor’s vast festival of Negritude. The exhibition of contemporary art, titled ‘Tendencies and Confrontations’ was little documented, but a film by William Greaves film captures something of the scale. Duke Ellington and Langston Hughes walk through the exhibition hall and perform to huge crowds. In one frame I think I can see The Mother hiding behind work by Christian Lattier. I like to think of Moody unwrapping the sculpture and welcoming it back into the studio and wondering about the conversations it must have overheard. As he says of the Concrete Family group in Wilmer’s article for Flamingo: ‘They really look as though they are talking about us!’[13]

§

In the first of C.L.R. James’s excitable and passionate ‘Letters from London’, his dispatches to the Port of Spain Gazettefollowing his arrival in London in 1932, he records a visit to the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Science Museum. He compares his experiences observing a high-speed plane with Rodin’s The Walker. He calls the Rodin statue ‘the thrill of the day’, and describes how it makes the ‘blood burn’:

I sat and watched it and when the body is still the mind moves. I reflected that a Greek who lived two thousand years ago could have sat with me and watched. He would have seen it with much the same eyes and feelings that I did. But the Schneider plane would have been meaningless to him. Three thousand years from now, some wanderer from the West Indies will walk down Exhibition Road. He will go into the Space Museum and see the latest thought-plane. (That vanished type of conveyance, aircraft, will be represented by models.) Will he see Lieutenant Stanforth’s plane? Only as one of a crowd of obsolete designs.

But in the Art Museum he will see the statue of man walking. It will be to him as it is to me. It cannot grow old. It cannot go out of date. It is timeless, made materially of bronze, but actually, as has been said of great literature, the precious life-blood of a master spirit.[14]

In London in 2019 you could repeat this experience by visiting the Tate Britain and looking at Ronald Moody’s great Johaanan (1936), acquired by the gallery in 1992. While apparently named after John the Baptist, the figure is androgynous, with the torso suggestive of a pubic mound. The face recalls the inscrutable expressions of Egyptian Pharaohs and representations of the Buddha. As James says: while the body is still, the mind moves.

Much of the writing on Moody reflects on the apparent serenity of the sculptures: it’s hard to avoid the meditative power of the heads with their inscrutable expressions. Rasheed Araeen, a consistent champion of Moody’s work, described it in terms that would temper the humanism underlying James’s rapture:

The acceptance and assimilation of bourgeois humanism by the native middle class in fact provides a common ground where the difference between ruler and ruled is forgotten and the humanity of both is mutually recognised and universalised. This of course takes place through a social process, the ambivalence of which enables the repressed desires of the colonized to be expressed as the universal human predicament. The serene silence or calmness of a Buddha-like face can camouflage the intensity of inner state of mind or feeling, and it is this feeling that seems to be profoundly expressed in the work of Ronald Moody.[15]

For Araeen, Johaanan has gritted teeth. Recognising Moody’s central achievement—keeping him in the frame, as Wilmer does so beautifully in her portrait—means honouring its complexity. His work conforms to no simple narrative. But despite years of disaster and neglect, Moody remained optimistic until the end, continuing to make sculptures and achieving recognition from Jamaica in the form of the Musgrave Medal in 1977. He deserves the last word, expressing his belief that art could embody and further philosophical truths, making them available for contestation and use: ‘My faith in man has not been shattered.’[16]

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.

You may also like to read:

- Configurations of Empire

- Exploring the Institutionalisation of Archaeology

- Harold Feinstein at Store X: An interview with curator Carrie Scott

Notes

[1] Stuart Hall and Bill Schwartz, Familiar Stranger (London: Allen Lane, 2017), p. 62.

[2] See Anne Walmsley, The Caribbean Artists Movement 1962–1972: A Literary and Cultural History (London: New Beacon Books, 1992).

[3] Stuart Hall, ‘Black Diaspora Artists in Britain: Three ‘Moments’ in Post-War British History’, History Workshop Journal, No. 61 (Spring 2006), pp. 1-24 (4).

[4] Dawn Ritch, ‘An Evening With Ronald Moody’, Jamaica Journal (September 1972), Papers of Ronald Moody, Tate Archive TGA 956/8/2/32.

[5] Valerie Wilmer, Mama Said There’d Be Days Like This (London: The Women’s Press, 1989), p. 106.

[6] ‘Ronald Moody Talks Sculpting’, West Indian Gazette (November 1961), Papers of Ronald Moody, Tate Archive TGA 956/8/2/24.

[7] For context see Dora Clarke, ‘Negro Art: Sculpture from West Africa’, Journal of the Royal African Society Vol. 34, No. 135 (April 1935), pp. 129-137.

[8] Frank Rutter, ‘Africa in the West End’, The Sunday Times, February 3 1935. This newspaper cutting, along with a review from the Observer, is pasted into the copy of the exhibition catalogue in the library at the Courtauld Institute of Art.

[9] Quoted in Mary Lou Emery, Modernism, the Visual, and Caribbean Literature (Cambridge: University Press, 2007), p. 95.

[10] Ronald Moody, ‘An Exile Looks Back’, transcript of BBC Caribbean Survey broadcast, January 1953, Papers of Ronald Moody, Tate Archive TGA 956/3/6/2.

[11] See the unsigned essay by Cynthia Moody ‘The Works of Ronald Moody, 1900-1984’, Papers of Ronald Moody, Tate Archive TGA 956/8/6/1.

[12] See Cynthia Moody, ‘Midonz’, Transition, No. 77 (1998), pp. 10-18.

[13] Val Wilmer, ‘Meet Ronald Moody’, Flamingo Vol. 4, No. 3 (November 1964), pp. 31-33 (33).

[14] C. L. R. James, Letters from London, ed. by Nicholas Laughlin (Oxford: Signal, 2003), p. 14.

[15] Rasheed Araeen, The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-War Britain (London: Hayward Gallery, 1989), p. 16.

[16] ‘Ronald Moody Talks Sculpting’, West Indian Gazette (November 1961), Papers of Ronald Moody, Tate Archive TGA 956/8/2/24.