by Fiona Anderson and Mark Turner in conversation

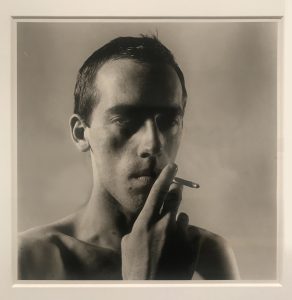

Fiona Anderson is a Lecturer in Art History in the Fine Art department at Newcastle. Her work explores queer social and sexual cultures and art from the 1970s to the present with a particular focus on cruising cultures, the HIV and AIDS crisis, queer world making practices, and the politics of urban space. Here, Fiona speaks to Mark Turner about her new book, Cruising the Dead River: David Wojnarowicz and New York’s Ruined Waterfront (University of Chicago Press, 2019).

Mark Turner is a Professor of Nineteenth and Twentieth-Century Literature in the English Department at King’s. He is the author of Trollope and the Magazines (2000), Backward Glances: Cruising the Queer Streets of New York and London (2003), and recently co-edited, with John Stokes, a major new edition of Oscar Wilde’s journalism for Oxford University Press. He has written about queer urban cultures and curated ‘Derek Jarman: Pandemonium’ at Somerset House in 2014. Mark is currently working on a project about the American gallerist Betty Parsons and her queer artists, particularly Forrest Bess. He co-founded the Queer@King’s research centre with colleagues in Arts and Humanities in 2003-4.

Katie Arthur is a PhD student in English at King’s researching the relationship between queerness and obscenity in the works of William Burroughs and John Waters.

Katie Arthur (KA): Thanks so much for joining us today. I’m not going to steer too much as I imagine you’ve got a lot to talk about given your shared interest in cruising, experiences of Queer@King’s, and your time as doctoral supervisor and supervisee. In fact, Fiona returned to Queer@King’s yesterday evening to share her research. Is there anywhere you’d like to start?

Mark Turner (MT): What if we start with you?

Fiona Anderson (FA): I thought you were going to say how we met, the origin story.

MT: That’s always cute. How about how you became interested in cruising? I’d already done it, once or twice, by the time you started.

FA: That’s why I came to meet you. I was doing a Masters at the Courtauld and I thought I wanted to do a PhD, but not right away. I wanted some time to think. So I was working as a receptionist at an advertising agency reading loads of Andrew Holleran, just all these gay novels from the 70s – no-one ever asked me what I was reading…

MT: Or why all the covers had bare-chested men on them.

FA: Well, one of the books was Backwards Glances by Mark Turner.

MT: Oh, great book.

FA: I read that and I thought, ‘I’d like to do a PhD with this person’. I came to London to meet you and I remember I was listening to Aretha Franklin on my iPod. I was a bit rushed and as we were talking I realised I could hear it still playing through my headphones and we had a good giggle about that.

MT: What made you want to move away from Art History? When both your undergraduate and masters degrees are in Art History, it is kind of a risk to move to English. Not many people do it, do they?

FA: To be honest, I found that more people come to Art History from another discipline. There’s quite a lot of art historians I know that have studied English Literature or a modern language or something like that. I did my undergraduate in Art History and I did my MA in Art History because I wanted to work with Mignon Nixon and I hadn’t had a chance in my BA. That was great but it was a whirlwind.

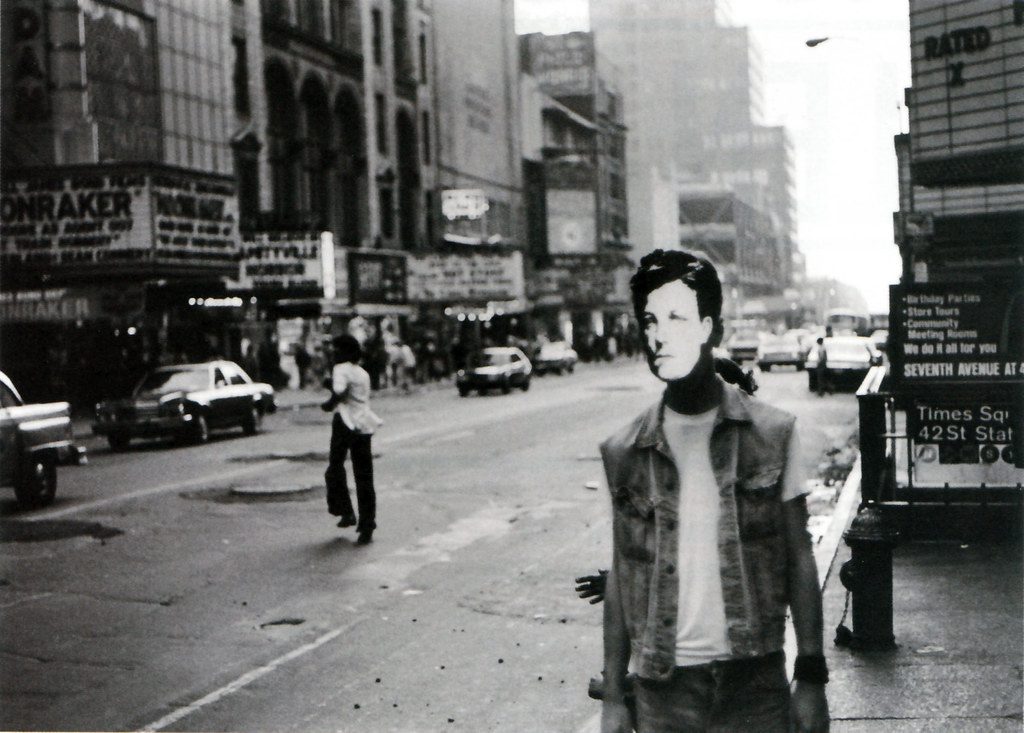

It was then that I first went to New York. I had actually already heard of David Wojnarowicz’s work. I went to a party somewhere in East London as an undergraduate and I was talking to someone who said, ‘Keith Haring? Forget Keith Haring, you need to get on Wojnarowicz, you need to buy Close to the Knives.’ So the next day I went to Gay’s the Word and got what was a first edition of Close to the Knives. The reason I moved discipline for the PhD, which I knew was a risk in a sense, was because Wojnarowicz’s practice is so varied and I wanted to do something about writing, and poetry, and lots of text. I thought: ‘In this person’s life, they were all ways of engaging with this world.’

Credit: rocor, flickr.

So I was testing it out when I was talking to you because in your book you’re working with visual material as well. The reaction I got from you, with me having no background in English, was very different to the one I got from some art historians which was ‘this is all very interesting, but it’s not really Art History.’ The next challenge was trying to explain that to the Arts and Humanities Research Council, so it would be something that they wanted to fund.

MT: Which it did, so it must have been a good explanation.

KA: The mixed-media research is interesting as it’s something that is central to both of your methodologies.

FA: Obviously you’re not the first person to do interdisciplinary work, but I think you do it with an irreverence that I found really emboldening. That’s been really influential on me.

MT: That’s second book privilege, I think. Having done your thesis book and got a job. I remember having lots of discussions with people about who to publish with and I was very keen that it had the possibility of getting into the hands of general readers. And back then, because this is a long time ago now, fifteen years, academic presses crossed that market much less than now. Since then presses, like Chicago, have upped their game and will publish books that cross over and find themselves in different kinds of bookshops. Back then it didn’t really happen, so you had to make these kinds of choices.

FA: And you didn’t have the Research Excellence Framework (REF)?

MT: We did have the REF. The REF certainly holds people back a bit before the first job, but I had a job and the first book behind me. I always wondered how the REF panel read Backwards Glances. I wanted it to be more accessible to the general reader as it felt like a very personal book. The idea for it initially came out of archival thesis work around the 19th Century. I wrote about it a bit in my thesis where I became fascinated with Turkish baths in the 1860s through a short story by Anthony Trollope.

So for Backwards Glances the work developed into this question about how a person in 1865, or 1900, or 1925, or 1950 found knowledge about their identity: where does that person get knowledge about their culture as a queer person? Where does that knowledge circulate or get transmitted? Where do you find out where to go? Which is why the book stops in the 1960s when you start getting different kinds of guides and it’s obviously very different now with the internet.

So it began with how one learns something and it focused on cruising as a mode of sharing information. The irreverence of jumping through different mediums – from contemporary photography, to journalism to novels – was a sense of cruising this archive in a very liberal way, and smashing and grabbing and putting things together informed by queer method, the kind of irreverence of queer methodology.

FA: And being ‘in’ your work as well. There’s not only irreverent nods to different cultural products or different disciplines, but to yourself. To take one example, when you’re in the Strand bookstore and Samuel Delaney taps you on the shoulder and says ‘That’s my book.’ The reader thinks, ‘Oh, I’m in conversation with this person now.’

MT: The interludes which go between the chapters are all seen through an autobiographical lens. The first one is a riff on The Wasteland, actually. I’m not sure if anyone gets that. But it tries this allusive thing, in conversation with T. S. Eliot, in a way. It’s this idea that very personal conversations are taking place and it did seem important, to be in conversation. Again, that’s queer methodology, to find your own investment and lay claim to that. I think it might not have worked if I hadn’t been in it.

FA: You’re in the book, it’s yours, but it’s not narcissistic or navel gazing.

MT: That can sometimes be the issue with queer writing, where it comes across as self-indulgent.

KA: That raises an interesting quandary that we face at the moment. It is sometimes said that the focus on subjective experience in queer theory or gender studies more broadly becomes navel gazing and dislocated from a structural political referent. As queer theorists, do you have to negotiate how much of yourselves you do put into your work, how much is useful?

FA: I think it’s a question of what is the material investment in your work. That’s what is so inspiring about the smash-and-grab approach because it’s connected to bits and pieces and I feel like my work as an Art Historian has given me a license to do English Literature or American Studies in that way. I think a problem with a lot of queer theory – I’ve been thinking about this a lot with comments that a number of speakers made at the Cruising the 70s conference – that a lot of American queer theory doesn’t have a politics. It doesn’t really have any relationship or investment in left-wing politics or organising or questions of political economy. It used to, there were moments, I recommend John D’Emilio’s essay ‘Capitalism and Gay Identity’ to so many people. It’s like the route queer theory could have taken.

MT: Or Gayle Rubin…

FA: Yeah, exactly. You give Gayle Rubin to students now and it’s still fresh and still radical. So many parts haven’t been taken up, so many challenges haven’t been taken up. Rubin is in her work but through a real grounding in material culture.

Credit: rocor, flickr.

MT: I guess that has its roots in the distinction in Anglo-American academic cultures. It goes right back through feminism or gender studies. We had Marxist Feminism in the UK and the Cultural Materialism of Alan Sinfield and Jonathan Dollimore over here, but a different kind of high theory route in the States. That materialist grounding is one of the things I’ve always liked about working in the UK academic context and studying queer stuff because it seems more urgent in a way.

FA: Because there isn’t that tradition of queer theory here?

MT: Possibly. Part of it is the academisation of ‘queer’ in America which happened quite quickly. Once the theoretical breakthroughs happened in the late 80s / early 90s, there’s a series of canonisations that take place with the establishment of departments and institutional structures. There’s something kind of useful about the lack of institutionalisation here. It is problematic in lots of other ways, lots of institutions still lack programmes in sexuality studies in the Humanities. A few, like Sussex, led the way in the 90s, but we never established one here alongside Queer@King’s in the early 2000s.

FA: It was talked about.

MT: We are actually doing that from next year, via a queer strand on the MA in Critical Methodologies route.

FA: They’ve got one at Goldsmiths.

MT: And Manchester is quite strong. But as a kind of route across the sector, it hasn’t taken hold. But that frees you up, weirdly. One of the things I found surprising about being at King’s, less surprising now because the department is so big and diverse, is that I could do what I wanted. So once the surprise of me being hired happened, I could do what I wanted. I was also hired the year before a couple of other queer guys were hired, working in American and Medieval Studies. We met other people across the faculty and it just became: ‘Oh we’ve got enough people to have a party.’

FA: ‘Let’s put on Queer Matters.’

MT: Let’s put on Queer Matters. Let’s establish this thing called Queer@King’s because there was someone in Classics, someone in French, someone in History. So there seemed to be a kind of critical mass. We established Queer@King’s in 2003/4.

FA: Queer Matters was 2003.

MT: I think it was the end of that year, it was a big year. I think that was one of the biggest ever queer conferences in the UK. 400 people, 31 countries, something absurd like that.

FA: When we were planning the Cruising the 70s conference, the team of us organising it were saying we wanted it to be the Queer Matters of today. Interestingly, Mandy Merck was talking about when she presented on a panel at Queer Matters and about that tension between Queer Theory professionalised, or Queer Theory in the US, and scrappy Marxist union-driven Queer Theory and academia in the UK.

MT: And those faultlines emerged within panels. Gendered fault lines within queer studies that we didn’t necessarily see coming. But also the international fault lines that emerged from having people from so many countries there. People would stand up from Thailand and say ‘That’s really interesting but in my country it just doesn’t work that way.’ Or from Sweden, and they’d say ‘No, no, beastiality means something specific in Sweden’ or whatever it is. There was an interesting set of transnational tensions which emerged partly around other categories: metropolitan/non-metropolitan; professional/non-professional; lead institution/non-institution…

FA: Bloody binaries.

MT: Exactly. They got pushed forward in the conference in quite a good way – and we had fun as well.

FA: Well, we’re still talking about it 16 years later.

MT: Exactly, a lack of imagination!

FA: They were heady days. We knew that they were and that they were temporary. It was something really unique. It was a time when only seven students would sign up for the Critically Queer module. How many do you have now?

MT: 60, with a waiting list.

FA: Exactly. We had to really argue for that module to stay on the books. I remember it wasn’t going to run and students complained that it was being taken off. The argument was that hardly anyone signs up and they were paying me as an external member of staff to run a course that seven students came to. It wasn’t an oasis but we felt that we had flexibility and agency in terms of forging where this discipline was going to go. It was a really supportive environment where you could talk about developing projects, support each other personally, get to know visiting speakers. At Queer@King’s meetings you’d have professors, like yourself and John Howard, down to MA and early PhD students, so you could get to know how a university works.

MT: It was democratic with the steering committee and also I think the informality was useful. Within academia, those institutes and research centres sometimes aren’t as informal as they might be. John would always talk about how Queer@King’s was really there for PhD students, as a home beyond the department context, where students should be able to flourish, and raise ideas and make the centre their own. That requires an amount of informality. I mean we were really informal so there may be a spectrum of informality but we also had tonnes of fun.

FA: It’s when you have to leave the fold and go to another university and you think ‘there’s barely any other queers here let alone a queer research centre.’

MT: So when did you happen upon cruising?

FA: I’d always been interested in HIV/AIDS histories and had written my undergraduate thesis on David Wojnarowicz, Keith Haring, and Robert Mapplethorpe. I became fascinated with ‘the pre-AIDs moment’ and how you could challenge this sense of it being, what I now talk about as being ‘viral momentum’, this hugely problematic sense of causality and shame that, now when we look back at this period, some people view it as ‘the last days of Rome’. I’ve always loved cities and I’ve always loved maritime history so I could include that but it would also be about that sexy 70s moment. It allowed me to do that, and the more I read about it and the more it seemed like there was a lot there.

Credit: dou_ble_you, flickr.

The other PhD project I thought about was Tangiers and gay sex tourism and the idea of the autonomous zone. It would be a totally different project. But, both of them at the edge of the land, this littoral imaginary. The idea of cruising as method came up partly because I realised I had sort of been doing it and partly because I realised I need to create a theory, a lexion, through which this could be understood. I knew it had to come out of the work itself and, instead of relying on the great work someone else has done, I asked if I could also establish a theory. Very much informed by Gayle Rubin, John D’Emilio, and others, through that a material history that can be applied to other cultural historical contexts as well. I remember being inspired by this line that Fab 5 Freddy said about the Fun Gallery: ‘We wanted a gallery that was like the work itself,’ about how to display graffiti in a downtown gallery. I thought, ‘can I do something like that?’ How do I write a PhD or a book that was like the work?

MT: How was the transition from PhD to book?

FA: It’s pretty different, the core is there.

MT: I’ll recognise it then. Bits of it. Some of the photos.

FA: ‘Somebody I used to know.’ The tone is different, I was more emboldened to do the theory stuff. Interestingly, one reviewer said it’s still not enough, you’re doing innovative stuff but you’re not signposting it. I think that’s actually a US/UK division, at the end of the day I’m still a girl from rural Scotland. The transition was difficult because of precarious employment and other things. I tried to get articles out of the book but it’s a book project, it’s not something that can be chopped up. There are a couple of articles that came out of it, one of them is very short, one of them is all the municipal history that the reviewers were like ‘hell no is this going in the book’.

MT: ‘That’s going into Municipal Studies. The Journal of Municipal History.’

FA: It’s actually in Shima: The Journal of Island Studies and it’s all about the history of the South Street Seaport Museum, very interesting.

MT: I must read it.

FA: I found the transition difficult initially because I was teaching five modules a semester all through the summer, making no money. Then I got a job at York so I had some research time but commuting made it difficult. Then I got a job at Edinburgh where I did some articles. I kept thinking that my research day would present itself to me and say ‘Come on in girl, write a book!’ And that never happened.

MT: I think it’s really hard with the constant teaching preparation. Depending on where you are and the job, you have more or less of that, but you’ll always have some of it. I remember that, one in the morning, churning out lectures, this kind of gruelling treadmill. But I didn’t have the same pressure 25 years ago, there were jobs around at least, few temporary contracts.

FA: But once that calms down, other things take its place: ‘I’m on the committee for this.’ So I thought, hang on, I’m really going to have to force out the time. I was very lucky that I was approached by the publisher, I think that gave me the kick that I needed. I don’t know if I would have been able to do it otherwise. I’d just moved house and was just about to start at Newcastle, and an editor from Chicago emailed me saying ‘We’ve heard about your work, do you have a publisher?’

MT: ‘Thank you, I do now!’

FA: I don’t know how they heard about it, but for Art History, Chicago are a great press. Throughout the whole process, I’ve felt extremely supported by Chicago. I didn’t realise how collaborative publishing was. You have reviewers and editors, and these great conversations over email that I found so enjoyable, almost a little seminar about queer history sometimes.

MT: I have a lot of faith in the old peer review system. It depends on whether publishers get the right reviewers and a good publisher will do their homework. It is really really important to see how two-three people will read the book. Someone is going to read it, you’re writing for it to be read.

FA: It’s different to articles. With books, they know you and they’re really committed to making it a better book. Hearing where reviewers thought my primary contributions were was great to see where to go next.

MT: I had a fun thing with Backward Glances where it had gone through the review process and the publisher, who was this fun maverick guy, showed it to someone else, just to give it a look. I asked who it was and he said, ‘oh, Ed White’ and I thought ‘that’s nice.’ It would have been awkward if it had gone through two reviewers and Ed White had said no. That, and Elton John bought it.

KA: I’m not sure we can top an Elton John reference as an ending. Thanks ever so much for your time and for sharing a little of King’s recent history with us. We look forward to seeing what comes next!

You may also like to read:

- Youtube, iPads, and videotape: Archives of HIV/AIDs activism

- ‘Gender blind casting’, who and what goes unseen?

- Painting in circles and loving in triangles: The Bloomsbury’s Group queer ways of seeing

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.

If you have any comments on this interview, or would like to ask Fiona or Mark any further questions, please use the ‘Comments’ section of this blog post.

Images reproduced with permission from Fiona Anderson, Mark Turner, and under Creative Commons Licenses from Flickr.

You may also like to read:

- Youtube, iPads, and videotape: Archives of HIV/AIDs activism

- ‘Gender blind casting’, who and what goes unseen?

- Painting in circles and loving in triangles: The Bloomsbury’s Group queer ways of seeing

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.