By Amy Lidster, Postdoctoral Research Associate, Department of English, @amy_lidster

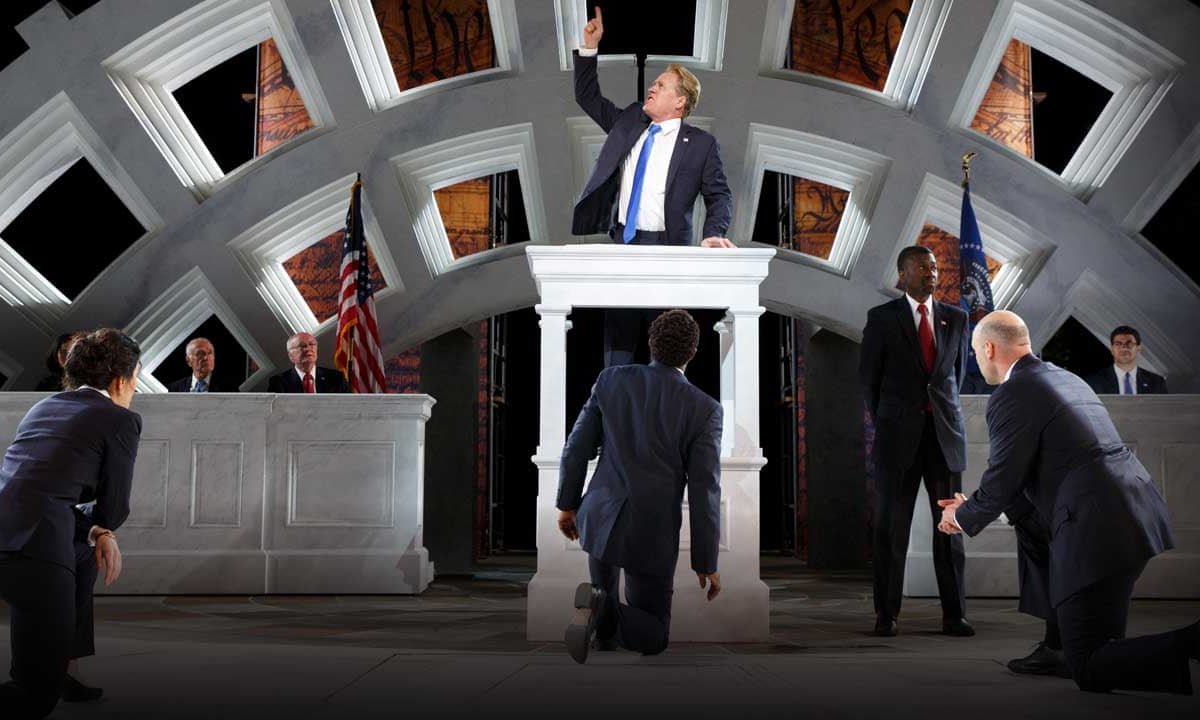

Productions of Shakespeare’s plays have been regularly used to comment on the political and public affairs of their performance moment – occasionally provoking heated responses. In 2017, for example, the Public Theatre’s production of Julius Caesar at Shakespeare in the Park prompted a media furore (led by Fox News), because the presentation of Caesar bore a striking resemblance to Donald Trump.

The Public Theatre, other news media, and Shakespeare scholars (such as Stephen Greenblatt) were quick to point out that Shakespeare’s play hardly condones the assassination of Caesar and that it explores, instead, the conspirators’ flawed and extreme reactions to a democracy under threat. But audience responses cannot be contained by a careful reading of the text, and, while a production may clearly announce its relevance to contemporary politics, it is difficult to pinpoint a specific application or to control public responses to it.

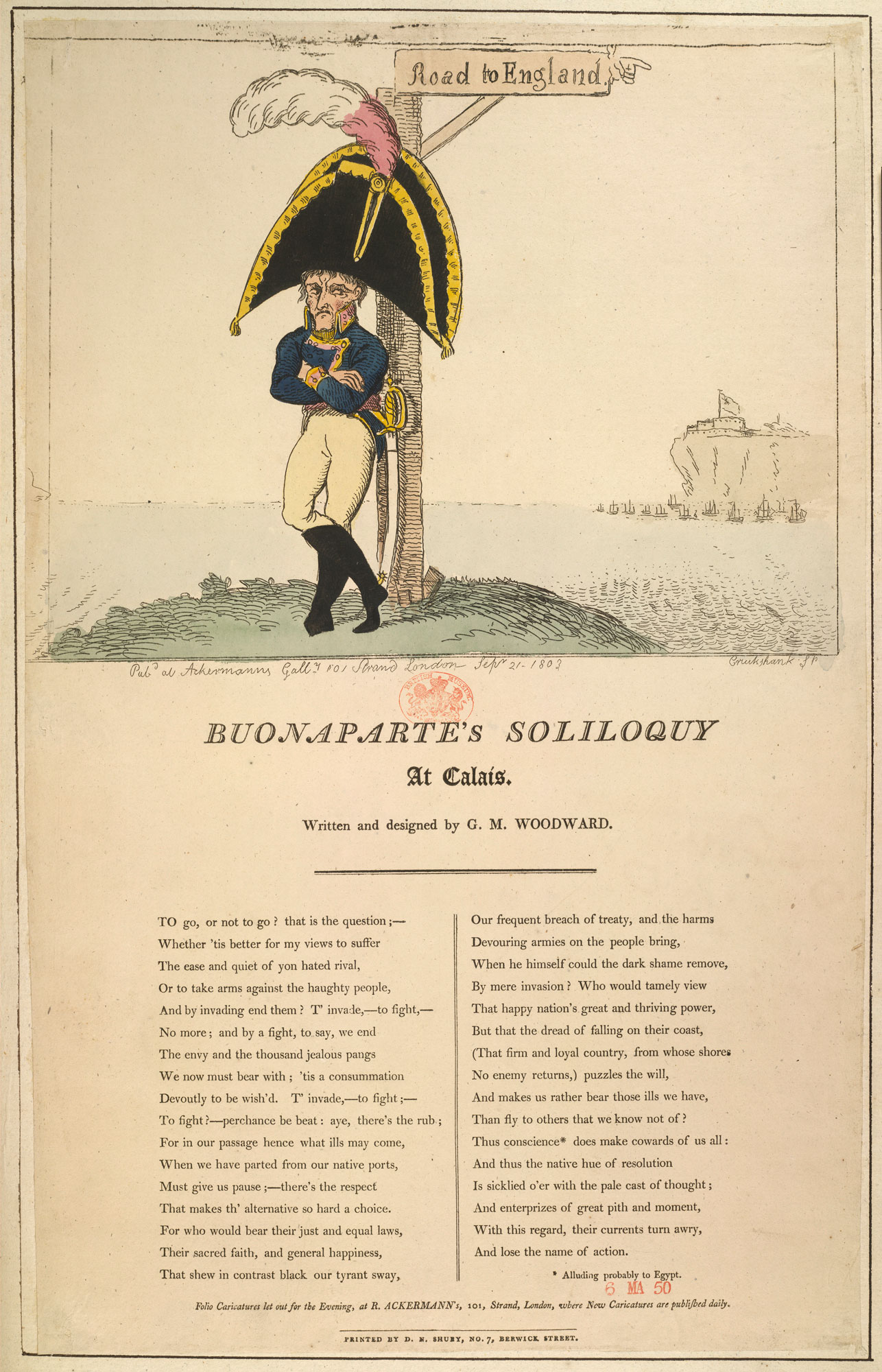

During times of war, the use of Shakespeare’s plays for contemporary commentary often becomes particularly urgent and direct – and there is frequently an assumption that such productions will put forward a clear message and offer partisan support for one side of the conflict. One theatre reviewer in 1787 recognized the propagandistic potential of theatre productions (including those of Shakespeare’s plays) and their wartime power:

“In times of peace, they evince wealth, improve genius, and give encouragement and employment […] But in time of war they do more. They alarm the enemy by infusing into them a magnificent idea of the national resources, which support the government; and examples of magnanimity, exhibited on the stage, stimulate the spectators even to enthusiasm, in exercising the virtues of patriotism at home, and in the field.”

(A Letter to the Author of the Burletta called Hero and Leander, 1787).

Some Shakespeare productions seem to fit neatly into this account, fashioning a patriotic, national theatre that supports the government’s military action and functions as a form of wartime propaganda. Perhaps the most famous production is Laurence Olivier’s film adaptation of Henry V during World War II. It presents a chivalric, airbrushed Henry, achieved by removing some of the play’s most troubling scenes, and was patriotically dedicated to the ‘Commandos and Airborne Troops of Great Britain, the spirit of whose ancestors it has been humbly attempted to recapture’.

Other examples can be found throughout Shakespeare’s performance afterlife. During the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), Shakespearean productions seem to have reflected prevailing anti-French sentiment: Henry V was staged every year in London with playbills that advertised the ‘Conquest of the French’ and King John featured new sections of jingoistic dialogue, as well as contemporary French costume, which prompted audience members to rally against and attack the actors who played the French characters. And interestingly, during the American War of Independence (1775-1783), Julius Caesar emerged as a key text in the colonies’ pursuit of liberty. Despite the fact that the play exposes the conspirators’ flawed reasoning (as defenders of the recent Shakespeare in the Park production point out), it was actually appropriated by the American colonists in support of independence and was advertised on playbills as presenting ‘the noble struggles for Liberty by that renowned patriot, Marcus Brutus’.

As part of my work on a new Leverhulme-funded project about ‘Wartime Shakespeare’, I am interested in exploring the possibility that most wartime productions are more equivocal – and, even when they appear to take a clear stance in relation to a conflict, the agendas of those connected to the production are much more diverse.

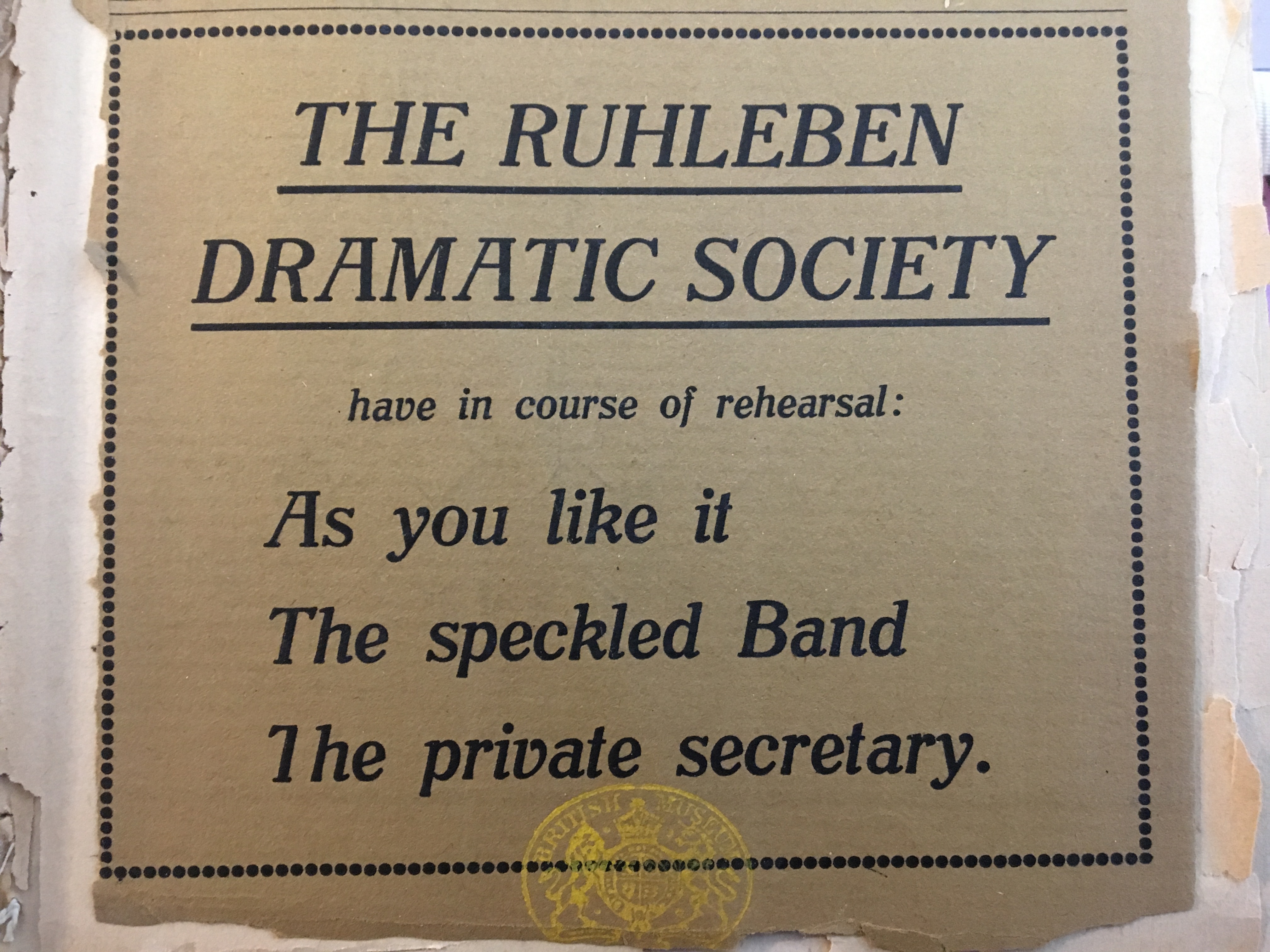

During World War I, for example, Shakespeare’s plays were regularly staged by exiled Britons in Ruhleben, a civilian internment camp in Germany. Accounts of these productions spread outside the camp as a part of a propaganda campaign by the German authorities to counter the widely circulating reports of the appalling living conditions in Ruhleben. These amateur productions functioned, on the one hand, as German propaganda, but, on the other, as a vehicle for allowed dissent by the internees that fulfilled a very different set of aims.

As I start work on this project, I am particularly interested in how the political sympathies of the implied audience (to adapt Wolfgang Iser’s ‘implied reader’) influence production decisions. Does wartime theatre primarily affirm the views of its audience? Or, to put it another way, is it more impactful (in terms of rallying emotions and possibly spurring action) when it reinforces, rather than challenges? And, crucially, how can this impact be measured?

Carl von Clausewitz memorably remarked that war is the continuation of politics by other means.

A glance at theatre history suggests that the stage also provides for a continuation of politics (and war) by other means. However, clear-cut applications to contemporary politics are not always easy to make. Unlike mass organized propaganda, wartime theatre does not usually involve a single propagandistic aim or source, and the relationship between production decisions and external factors, such as predicted audience responses, economic considerations, and wartime reporting, is an increasingly complex one. During this project, I am hoping to question some of the commonplace assumptions about propaganda and its relation to the arts, exploring how and when wartime theatre shapes a conflict and its narratives.

‘Wartime Shakespeare: The Fashioning of Public Opinion through Performance’ is funded by The Leverhulme Trust and directed by Professor Sonia Massai (PI, English), Dr Jan Willem Honig (Co-I, War Studies), Professor Ned Lebow (Co-I, War Studies), and Dr Amy Lidster (Post Doctoral Research Associate, English). It examines how Shakespeare has been used in performance to inform public opinion during periods of war that featured British involvement between the seventeenth and twenty-first century.

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.

Featured image: Nicholas Hytner’s 2003 production of Henry V, with Adrian Lester as Henry, by Tristram Kenton for The Guardian.

You may also enjoy

Reflections on teaching in the age of Trump and Brexit

‘Yours truly, Lady Macbeth’, creative writing by Shakespeare Academy pupils.