by Julia Pascal, Research Fellow, Department of English, King’s College London

It’s a century after some British women were allowed to vote, and a statue of the suffragist Millicent Fawcett has been unveiled in Parliament Square, so why is women’s presence on the English stage still unequal to men’s?

In a recent survey, the Sphinx theatre found that just a fifth of English theatres were led by women, who between them control just 13% of the total Arts Council England (ACE) theatre budget.

The feminist campaigning organisation the Fawcett Society has called for quotas to get more women into key positions, after its Sex and Power Index revealed startling gender disparities in the public arena. The situation in theatre, where I have worked all my life, is a startling gauge of the marginalisation of women.

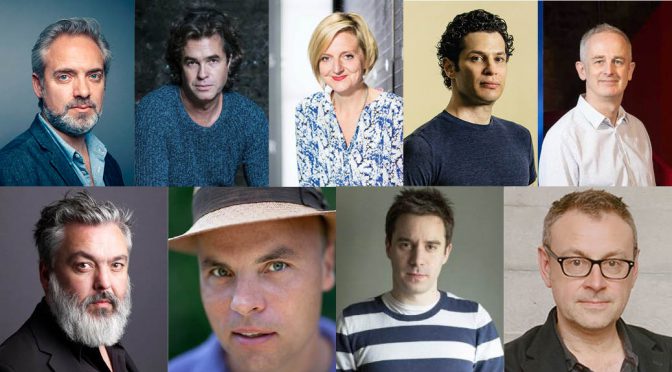

The Conference of Women Theatre Directors and Administrators began auditing the number of females on stage in the 1980s. That we are nowhere near equality, almost 40 years later, was only too evident at the Olivier awards this year, when the prizes for best director and best new play went to men. When women do not have equal representation in theatre, it is impossible for them to have an equal chance of winning prizes. The Equal Representation for Actresses campaign group is among those pushing for change, but the male ruling elite refuses to share power.

Postwar British theatre declared itself to be the vanguard of a more equal society. From 1956, a new wave known as the ‘angry young men’ celebrated working-class playwrights, directors and actors.

Male rage was hailed as a revitalising force. Women’s rage was not. However, this working-class male movement never gave women equal opportunity. Sixty-two years later, female talent remains un-nurtured.

Even today, female playwrights and directors are atypical. Shakespearian gender-swapping has been mooted as a partial solution. One example is Michelle Fairley playing Cassia [a gender-swapped Cassius] at London’s Bridge theatre. However, such theatrical novelty only serves to distract from the main issue – the absence of contemporary dramas reflecting the complexity of women’s lives.

Cross-gender casting fails to question the over-representation of dead and living male playwrights. It does not address the fact that half our contemporary creative world is missing.

Why aren’t more women active demonstrators against this injustice? One reason is a justifiable fear of blacklisting. Some of the privileged theatrical knights who have led our flagships, the National Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company, have opposed gender parity. Consequently, women, who must seek male directorial approval to be employed, have dared not speak their name.

There are structural reasons for marginalisation. Drama schools educate female graduates to expect lower employment levels than their male peers. The actors’ union, Equity, the majority of whose members are female, rejects calls for equal representation. Most important of all is the position of Arts Council England (ACE).

The term ‘diversity’ reduces women – the majority of the population – to a minority…

This unelected quango crushes female ambition by boxing women into a category called diversity. This term reduces women – the majority of the population – to a minority. This promulgates the lie that females are diverse and males are mainstream. Orwellian double-talk maintains male dominance.

The exclusion of women from equal employment at all levels flouts both civil and human rights. The theatre is a serious, international political platform. It is a parliament of the arts, a form of soft power and a cultural territory as important as any physical land mass. With this abnegation of female flair, audiences are robbed of the full human story. These audiences are 65% female. There has never been a female artistic director of the National Theatre or Royal Shakespeare Company. Sir Nicholas Hytner, artistic director of the National Theatre for 12 years, until March 2015, never directed a play by a woman during that time.

Women may occasionally appear as actors, directors and playwrights, but the English stage is devoted to worshipping male narratives. Where are the histories of our mothers, sisters and grandmothers?

In December 2017, the recently appointed chair of ACE, Sir Nicholas Serota, announced a 50-50 male-female split on its national council. What we need now is 50-50 employment for female actors, directors, playwrights and creative artists.

We may hate the concept of a quota system but decades of disenfranchisement mean that female artists and audiences have been cheated. When women’s human rights are acknowledged on the English stage, and when theatres are equally shared among expert professionals of both genders, only then can we say that our theatre is truly national and democratic.

This article was originally published on The Guardian’s ‘Comment is free’ blog. Read the original article here.

Featured image: composite of the winners and nominees for best director and best new play at the 2018 Olivier Awards.

You may also enjoy

The Long Read: Just Women and Violence

Hailey Bachrach on ‘gender blind’ casting at Shakespeare’s Globe

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and not those of the English Department, nor King’s College London.