by Dr Adelene Buckland, Senior Lecturer in English Literature

On 21 March 2018, I gave a talk for the London Arts and Humanities Partnership (LAHP) ‘Arts and Society’ series at Senate House. As I spoke, students in the building performed a banner drop in support of the lecturers’ strike over pensions, and had the fire exits drilled shut on them by those who did not support their protest. It was an odd moment in my career, to be speaking on Darwin while unaware of political events unfolding elsewhere in the building, and it caused me some reflections on my paper.

The work was drawn from an essay forthcoming in Philological Quarterly in a special issue on ‘earth writing’, the outcome of a symposium I attended in Düsseldorf in April 2016, when I was five weeks pregnant with my third daughter and unable to drink much of the wine (and unable to tell anybody why). The essay is also poignant for me because it marks (I hope) the culmination of what I guess might be called the ‘early career’ phase of my research, on Victorian literature and geology.

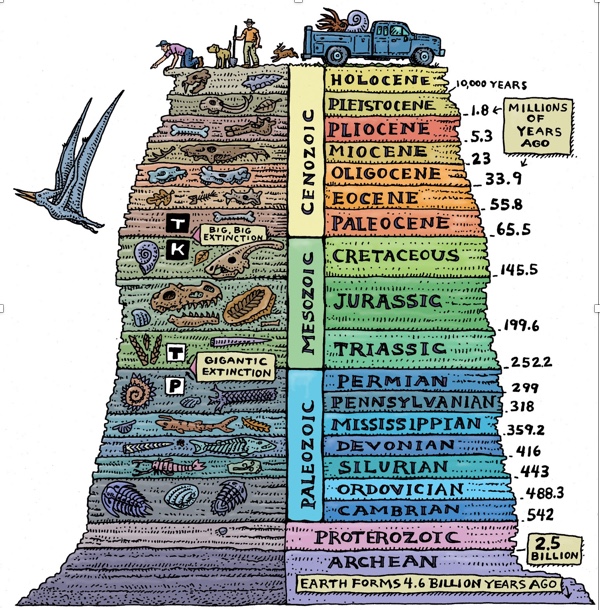

Reviews and citations of my book, Novel Science, have sometimes surprised me in coming from an ecological perspective: in all the years I worked on the book, I hadn’t really thought about it in these terms at all. Since then, I have often been asked questions about the new geological Epoch in which we are now said to be living, the Anthropocene, and its relationship to my historical research. I wasn’t happy with any of my answers.

What was the relationship between the period in which geology had emerged as a recognisable modern discipline, and this new Epoch in which humans are said to be transforming the earth – for the worse – on a geological scale?

In another sense, however, the paper also came directly from my teaching at King’s. In the autumn of 2016, now heavily pregnant with my third daughter, I co-taught the module Victorians Abroad with Ian Henderson. I have taught on that course almost every year since I started work at King’s in 2012, but never with Ian. His lectures were inspiring. Just over half way through the course, he spoke on For the Term of His Natural Life by Marcus Clarke, a novel on the Australian penal colony, and set settler colonialism in ever-wider contexts, ending with the Anthropocene. How did patterns of migration look at a level that took in the whole of human history, Ian asked?

After the lecture, Ian told me about his bigger research project, on the forms of imagination granted in literature to white audiences, and the kinds of imagination those same texts deny to the colonised and indigenous subjects they describe…

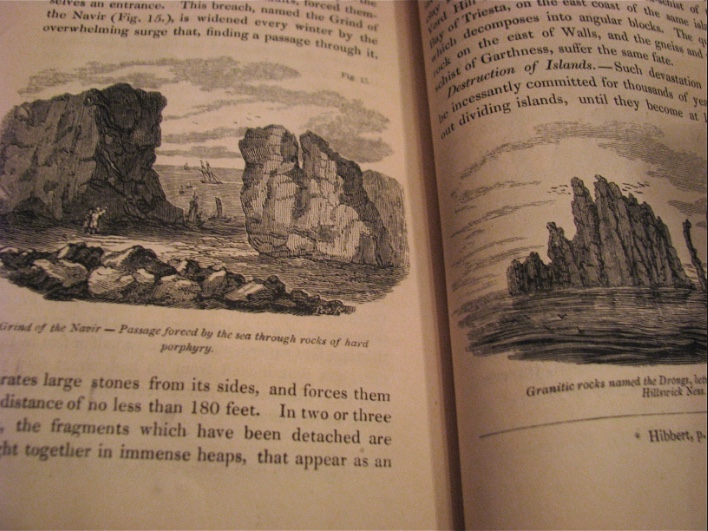

The next week, I rewrote my lecture on Darwin’s Journal of Researches in response to Ian’s ideas, and it formed the first stage in the work for the essay from which my LAHP paper is drawn. The lecture was already partly stolen from Clare Pettitt, whose own wonderful lecture on Darwin’s Journal had focused on Darwin’s literary reading as he voyaged around South America as a ship’s naturalist. I continued to use much of her material – looking at Darwin’s reading of Milton, the geologist Charles Lyell, and Maria Williams’s translation of Alexander von Humboldt’s Personal Narrative.

But now I also explored the ways in which current thought about the Anthropocene might have been shaped by Darwin’s ideas about what constituted the geological imagination (and how it might have been structured against, or built upon, Darwin’s sense of the kinds of imagination the peoples of South America might or might not have possessed).

Later, I shared an early version of the paper with two of my friends in the department, Lizzie Scott-Baumann and Rowan Boyson, and they suggested – among other things – that I devote greater space to exploring the ways in which the Yaghan or Yamana people with whom Darwin had his most famous encounters had conceptualised the landscapes and species interrelationships in different terms. Almost at the same time, a reviewer on a grant application told me to be more explicit about the methodologies by which I would include non-European voices – advice supported and sharpened by Sadiah Qureshi, a good friend and fantastic historian at the University of Birmingham, who generously read and commented on my application.

Was Darwin’s very conception of the geological imagination shaped by the scientific imaginaries of the peoples he encountered…?

So, using Sujit Suvasindarum’s method of ‘cross-contextualising’ the sources of non-Europeans by reading them against and within European scientific texts (and vice versa) I tried to think harder, in my conclusions, about the ways in which Darwin’s very conception of the geological imagination may have been shaped by the scientific imaginaries of the peoples he encountered (and whom he denied could possess an imagination at all). I could only do this sketchily and suggestively at the end of this paper – but for me it marks the beginning of a new phase in my research career, and a new approach to method and citation. This feels risky and uncertain, and I have a lot to do to make it work. But it also feels exciting.

I am going part time in September to try to bring some sanity to family and academic life, and my new project on maternal instinct in colonial encounter will now take longer than I imagined. It will also take longer because I realise that these new approaches to method and citation will demand a serious amount of reading and immersion in vast areas of the discipline as yet unknown to me. I want to do it justice.

So I am now beginning with a shorter study of ‘artificial mothers’, beginning with Alfred Russel Wallace’s The Malay Archipelago, which will focus on these ideas about the imagination and anthropology, but also consider technology, robotics and posthumanism. The paper on the Anthropocene is as much an ending as a beginning, though: I finally have some kind of answer to the question about how my work on Victorian geology might speak to the Anthropocene.

Inventing a new, geological scale for the imagination depended upon making invisible a range of smaller, slower, more intimate acts of imagining in deeply problematic ways with which we continue to grapple.

Other questions of invisibility seem important now, too. In his last lecture of the series, Ian reminded students of our intellectual inheritances from the Victorians, who also constructed the university as we know it. In doing so, they constructed knowledge in such a way that certain kinds of experience have been excluded from its provinces. The fact that I was now eight months pregnant, and that none of us had mentioned it (except in one embarrassed aside) was one of them. The experience of giving a paper at a LAHP seminar, while students beneath me were silenced for their support of their lecturers, has now become another.

Silences matter…

It seems trite to say it, but in the Epoch of the Anthropocene, which is the product of a geological imaginary that works at scales so large as to efface human difference and both intercultural and interspecies imagining, and which is also the product of capital accumulation built on the exploitation of geological resources and often justified by lazy Darwinian economics, these silences matter.

I hope that my future research will more proudly intertwine my personal experiences, beliefs and commitments than it has done in the past – as well as more loudly citing all those to whom my work has debts, including debts of friendship, gratitude and solidarity.

Featured image: The Earth at night, a composited image of the world during the Anthropocene. (Photo ©: NASA/Wikimedia Commons)

You may also enjoy:

Metaphor in Literature and Science #BSLSWinter2017

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.