by Ella Parry-Davies, PhD researcher funded by King’s College London and the National University of Singapore, working on performance, place, and memory, and Myka Tucker-Abramson, Lecturer in Contemporary Literature. With a postscript from Kélina Gotman, Lecturer in Theatre and Performance Studies

“The male is a biological accident: the Y (male) gene is an incomplete X (female) gene, that is, it has an incomplete set of chromosomes. The male is an incomplete female, a walking abortion, aborted at the gene stage. To be male is to be deficient, emotionally limited; maleness is a deficiency disease and males are emotional cripples.

SCUM is too impatient to wait for the de-brainwashing of millions of assholes. Why should the swinging females continue to plod dismally along with the dull male ones? Why should the fates of the groovy and the creepy be intertwined? A small handful of SCUM can take over the country within a year by systematically fucking up the system, selectively destroying property, and murder.”

(Valerie Solanas, “The Scum Manifesto”, 1967)

“If sexism is a by-product of capitalism’s relentless appetite for profit then sexism would wither away in the advent of a successful socialist revolution. If the world historical defeat of women occurred at the hands of an armed patriarchal revolt, then it is time for Amazon guerrillas to start training in the Adirondacks.”

(Gayle Rubin, “The Traffic in Women”, 1975)

“Homoexplosion is a radical queer/ trans group of fly fatherfuckers. We advocate people fucking in the street and burning shit—especially cops.”

(NYC Queers Bash Back Against NYPD, 2009)

We live in a moment of amplified violence, or at least a time in which certain kinds of violence have become more visible. New forms of surveillance, and heightened attention to the reported arming of both so-called individual terrorists or terrorist cells, as well as hostile nations, often speaks less to new threats than to carefully crafted states of emergency. However, at the same time, we are seeing an increasing incidents of hate crimes, intensified and increasing police brutality and state violence, and the continued expansion of the War on Terror.

How we describe and think about violence matters. Particularly in moments in which violence is hyper-visible.

This sense of amplified violence is not just in the newspapers, our Twitter feeds, and often in our peripheral vision. It has also saturated our language, our psyches, and our institutions. The university is not immune. The neoliberal or managerial university militarises our place of work and study turns us into its soldiers. We are asked to report students under the PREVENT agenda, and to hand over our registers to the home office to monitor international students. The University of Manchester recently sent out a letter to 900 employees announcing they were “in scope” for redundancy.

Perhaps even more insidious is the militarisation of the very banal language we use to describe our daily activities. We discuss tactics and codify strategies. We try to ensure our research has impact. Our powerpoint presentations have bullet points. We issue trigger warnings.

What, then, does it mean to return to and focus on bodily violence as a differential, to think about which bodies are targeted, and to what extent violence can also be used to individually or collectively un-target oneself. This is the question we asked in our Text, History, and Politics seminar “Just Women and Violence,” an event that opened with the question “What would a syllabus look like without men?” and invited participants to imagine what a syllabus would look like “if men had to suffer what we seem to think nothing of asking women to, asking them to confront redundant, subjugated, castrated and dead male bodies – and in turn to confront women’s desire, women’s violence and women’s justice?”

In doing so, this seminar followed in the footsteps of numerous other theorists of revolutionary violence to consider the potential (and pitfalls) of violence as a tool to resist or end that targeting, and of violence’s potential not as a tool of enforcing and creating gender hierarchies, but overthrowing them.

This seminar unapologetically focused on dead and castrated male bodies, and on women’s acts of violence and women’s demand for justice. It did so through an imagined syllabus, one that spanned history, nations, and genres, and that moved from textual to representative to bodily violence, ranging from discussions of representations of the Palestinian revolutionary Leila Khaled and plane hijackings, the exclusion of women from early modern syllabi, the role that violence played in the life and writings of medieval anchorites, and the possibility of women writing lyrics organised not around love, but around violence and hate.

In response to this event we have taken four provocations from comments and discussions we had before, during and after the event, and responded in dialogue.

1. All Politics is Violence.

“By ‘violence’ here, I am [referring to the] omnipresent forms of structural violence that define the very conditions of our existence, the subtle or not so subtle threats of physical force that lie behind everything from enforcing rules about where one is allowed to sit or stand or eat or drink in parks or other public places, to the threats or physical intimidations or attacks that underpin the enforcement of tacit gender norms.

Let us call these areas of violent simplification.”

(David Graeber, Dead zones of the imagination: On violence, bureaucracy, and interpretive labor, 2006)

“The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the ‘state of emergency’ in which we live is not the exception but the rule. We must attain to a conception of history that is in keeping with this insight. Then we shall clearly realise that it is our task to bring about a real state of emergency, and this will improve our position in the struggle against fascism”

(Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Philosophy of History, 1940)

As the “diversity of tactics” debates that marked the anti- or alter-globalization movement have taught us, the debate about what gets called violence and what doesn’t is fraught. It’s fraught because it matters. A lot turns on whether you think that smashing the window of a hedge fund for its role in a financial meltdown, say, is violent, or whether you think the policemen protecting those windows are violent. At stake is the question of whether we think that we live in a generally civil, sociable, and peaceful society that must be protected from eruptions of exceptional and anti-social acts of violent transgression (a riot, a terrorist attack, a murder, a violent protest), or whether we think our daily lives are themselves saturated by violence (whether as perpetrator, victim, or often in complicated ways, both). By beginning with the proposition that all politics is violent, we shatter the fantasy, denied to most, that business as usual is anything but violent.

Is Graeber’s sense of violence that which this interlocutor had in mind when she described all politics as violent? Insofar as political action and experience are predicated on structural violence or its threat, the statement holds. But if the “simplification” Graeber refers to describes the loss of imaginative potential, does it also suggest how this statement might prevent us from imagining a politics that isn’t violent? Surely another kind of politics is what we might precisely try to imagine? I’m concerned that praxes of de-escalating bodily violence, of creating and sustaining refuge, or of critical care, for example, are depoliticised according to that logic. In other words, I am cautious that this statement, to use Saba Mahmood’s terms, “elides dimensions of human action whose ethical and political status does not map onto the logic of repression and resistance”. Could we look instead towards capacities for ethical or political action whose imaginations do not find their definition in violence alone?

2. All syllabi are violent.

Syllabi are a technology for determining what violence is visible, what violence gets named as violence, and what violence goes by the day of reproduction, security, safety, and even care. Or perhaps we could go even further. Perhaps we could say that syllabi are themselves products of the enlightenment drive to abstract and rationalise knowledge, which was is itself based itself on the brutalising violence of colonialism, a process that Sylvia Federici and Maria Mies have taught us has always gone hand in hand with witch burnings and other technologies that sought to create new gender hierarchies and subjugate women’s labour to reproduction.

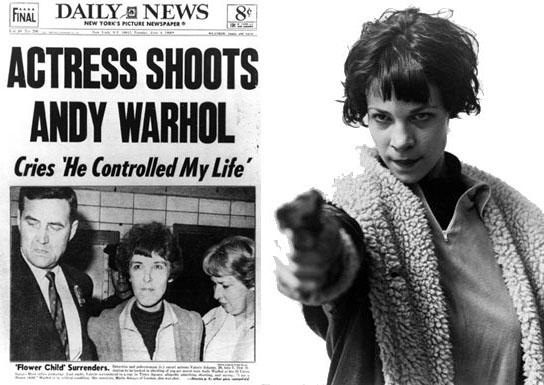

But, as the decolonise the curriculum movement has suggested, perhaps a syllabus can function differently. Perhaps a syllabus can erupt these abstractions, these assumed knowledges, and the violences that created and propagate those knowledges. Anyone who has ever taught a text like “SCUM Manifesto” – written by Valerie Solanas who is best known for shooting Andy Warhol – knows what I mean. Upon reading its proclamations of anti-male violence, the machine of rationalisation and control takes hold in the classroom. Students tend to respond with either anger (“She’s so violent. This isn’t helpful.”), discomfort (why does she hate men so much?) or rationalisation (“well I heard she was mentally ill.”). But given time, some students begin to shift, begin to wonder if her violent rhetoric and even violent rhetorics are justified; to wonder why her actions are irrational, violent, or psychotic, but any number of equally violent narratives or indeed the work of Warhol itself is not. Or begin, at least, to ask: what other violences don’t make us this angry?

Perhaps one goal for a different kind of syllabus would be to use violence to overturn what we mean by violence and who gets to define it.

We are inspired here by critical syllabi such as this Trump syllabus, and particularly this syllabus entitled ‘Islamophobia is Racism’.

3. Violence is not the answer.

If violence is an absolute, is its absolute alternative nonviolence? Could we conceive of nonviolence, rather than through lack, instead as an active principle and practice (in Sruti Bala’s words) “for the entire community, requiring a collective effort”, which can “performatively transform codes of institutional violent action into nonviolent acts”?

At the seminar, Luke Roberts discussed the “epic measures” of Alice Notley’s poetry, which on the page seem to explode out of their quotation marks, or at least stress the fragility of the constraints metering them:

“A woman” “then picked him up” “& folded him,” “his

clothlike body,” “till he was” “a small square shape” “Then she

laid him” “aside” “‘Must we continue” “to live in” “this corpse of him?’”

“a man asked”

Is it possible to find a form of political action that does not oppose violence as its negative, but exceeds it?

4. This event was violent.

What does it mean that our event began with the unapologetic demand for dead and castrated male bodies, particularly in the diverse and inclusive space of the university? Was this event violent to the men who participated and those who perhaps stayed home, terrified at what Bacchanalian violence would await them should they dare to enter? Would it be a problem if it was?

For me, the manifesto-like quality of the premise of the event and some of the texts it invoked at its opening catalysed a process of defamiliarisation – making strange. Laying on the table ideas that are upsetting, distasteful, inappropriate or otherwise excluded from the proper terms of conversation in this setting makes them the starting point, not the end point, of discussion. And as starting points they open up possibilities for thought that were not previously available, and therefore expose the boundaries marking out what is included and what is excluded from discussion. If violence done by women is marked as monstrous, unnatural, or pathological, taking it as the point of departure overturns the terms on which violence towards women and all people ever passes as normal, natural or unremarkable. For me, the value in the radical and unapologetic thrust of the event was not to come to a place in which women’s violence became the solution, but was to expose the mechanisms of a discourse that rendered it invisible or unspeakable in the first place.

Postscript

by Kélina Gotman

I am at home. It is quiet. I am reading Sara Ahmed. Her language is measured; it is angry; it is calm; it is outraged. She has decided to write a book, Living a Feminist Life (2017), in which there are no men cited. This is not done in a spirit of violence or exclusion; it is an attempt to reinscribe, to rewrite, to remake a family, a community, to cite women, brown and white women. There is a tone of urgency, a simplicity that unravels painful complexities, difficulties, intimacies; her writing is halting, it is clear.

Perhaps it is violent, it aims to unravel violence, to show, to expose, but in doing so she exposes herself. She knows this is painful; it is less painful, perhaps, than not exposing what she has been through, she and all the others; that to expose is, as she puts it, to make a problem, a problem that wasn’t seen, that becomes seen and therefore becomes, as it were, a problem. That that is never fun, never celebrated, welcomed. That to do so is to be a “killjoy,” the one who refuses to go along with the institutional sexism or racism that appears as if not merely a veneer, but something deeper, in the marrow of the bones of the building. She dismantles the building. She is outside the building. She has expulsed herself; she is stronger, too; she is not alone. There is peace in this language, just as there is blinding rage. Perhaps what this language does is to unravel what we may think of as the violence of the response, the response to violence; that to say, clearly, to be in one’s truth, to be in truth, that is to say, to see, without compromise, that that does something other. It shifts the coordinates. It shifts them to where you are, you standing there. That you standing there is right; that it is not wrong. That that is already to right a wrong; it is already to right. That to stand, there, or to sit; to be in that place without apology is already to be beyond joy or killing joy; it is perhaps, we might say, also, beyond nonviolence. It is a saying, and in the saying, there is a showing, and it is really, really simple. That this hurts, and that this is there.

And it is not that it is a man or a woman that did this; it is not that it is a white or a brown or a black person that did this; an aboriginal person or a police woman; it is that we are here in the observing of what it is that is said, done. And if we are there, observing, saying, and we can hear all that, perhaps then we are somewhere on a road to civility. I write this thinking too of the violence men like women suffer in a world that punishes those not boy enough; that that is violent. That that breeds violence. That to take care of our boys and our girls, that they should not be (become) boys or girls, that that too is to nurture, to make civility. And thus, if we carve out a space – a syllabus, say – perhaps a room – within which women might enter, or men might enter, or women and men might enter, or boys and girls, that what matters should be the conditions of speech, that they should always be exposed, again and again and again and again. That what that means is that we should – all – be exposed to the complicities, the hierarchies, the silences that we too nurture or allow, that we too carry and do not see or do not wish to see, as the punishment, Ahmed reminds us, would be too great. It is difficult to do this work of seeing. It is this work of seeing that we cannot but do.

And so, thinking this, writing this, I find that I don’t know what it is to do a syllabus that would unravel violence by showing another sort of violence; except that in that explosion of violences, there might be a cancelling out, a quieting that takes place; that takes the place of all that violence. I find myself wondering, again, whether in the unravelling, there might be a space of contemplation, of self-observation, and if that might not become contagious, just a little bit. That if we are all to find within ourselves the ways in which these structures of violence are perpetuated, the world might not be more civil, more caring, just a little bit.

It may be that the first thing to do is make a space, invite the women in; but these women will have a lot of different things to say, in their being white or black or brown women, women from this or that era or class. That some may find themselves sharing in love with trees, with companion species – Donna Haraway’s favourite term – for example. That, as a student wrote to me recently, there might not be just women vs. men, say, or race, but also all the complex webs of nonhuman lives that make us too, that make this world a complex and a vibrant and a full one. That to carve out a space for women is to allow something in, but it is also to make thicker a wall; perhaps the wall is the first bastion of the defense, the first port of call for a world without walls. That to take down, we have to build. That we cannot just take down. Not yet. But if we don’t take down now, when do we take down? When is it enough, this war of the sexes? What if at the vanguard there is a radical stepping away, a refusal to fight on those terms, on that ground, in that language – that violent language of violence? What if we were to imagine a syllabus in which there was no violence? That doesn’t mean no anger or rage, no destruction or birth. Perhaps it means a sort of engagement that is aloof of those rules, that articulates its own space of autonomy – an autonomous zone that is, that aims to be, on its feet, in its language, in its truth, in its observation, already inhabiting another sort of freedom. It is not easy, this work of freedom. This language with which to write, to think, to feel. This sisterhood, this world, it is not easy. Following Ahmed, it is our “homework,” too, to take home all this from over there – the “sweaty” conceptual labour of thinking what the language does, what the gestures do, when they make us feel this way.

This is not the end.

Featured image: Photograph by Drew Angerer/ Getty

You may also like to read:

What is to be done? The politics of reaction

People and Poems at Political Demos

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.