Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is an evidence-based psychological therapy, most commonly used to treat anxiety disorders and depression. CBT is a talking therapy that explores the relationship between thoughts, feelings and behaviours. It is a structured, goal-oriented, skills-based treatment that uses both cognitive and behavioural techniques to change the way an individual thinks (cognitive) and what they do (behaviour). It has proven to be successful, leading to remission in approximately half of patients with anxiety or depression. Here we give an introduction to the theories and techniques used in CBT.

Cognitive theory

CBT is based on Beck’s cognitive theory of emotional disorders 1. This model hypothesises that cognition influences emotional, behavioural and physiological responses. Within this model, cognition (or perception) is considered at three levels: core beliefs, underlying assumptions, and automatic thoughts 2,3,4. Core beliefs are thoughts and expectations about the self, others and the future that develop partly in response to one’s life experiences (although there is evidence for a genetic influence on personality and beliefs too) 5. Assumptions and rules about life are developed, which are consistent with these core beliefs. Based on these beliefs and assumptions, automatic thoughts are triggered by specific situations and are often accompanied by a physiological response.

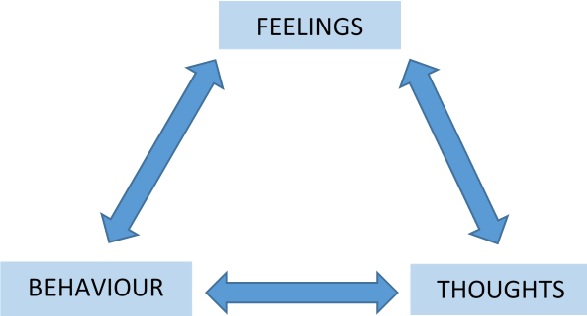

If one thinks upsetting thoughts, one will feel upset. This makes one more likely to do something such as, isolating oneself or ignoring responsibilities. This behaviour reinforces negative thoughts and intensifies these feelings.

Behavioural theory

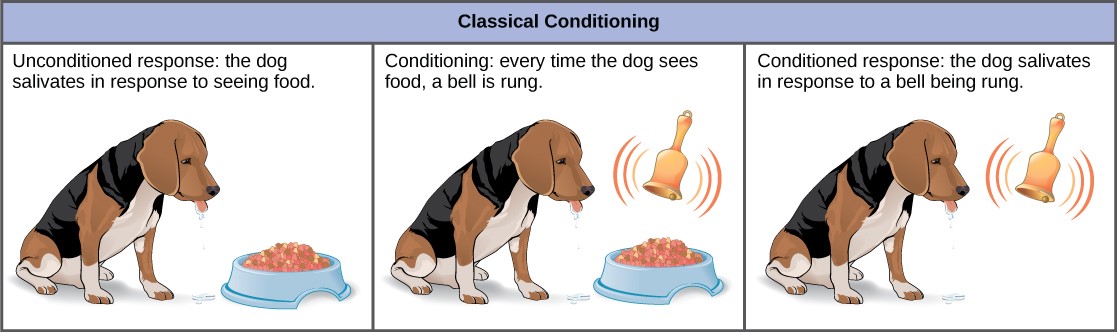

Patterns of behaviour are often the result of learning with regard to anticipated consequences. Such learning is described as conditioning, and there are two types: classical and operant conditioning. Classical conditioning (first introduced by Pavlov and later developed by Watson)6 involves learning to associate an unconditioned stimulus (e.g. food) that produces a particular response (e.g. salivation) with a new (conditioned) stimulus (e.g. a bell), which then evokes the same response.

Operant conditioning is a process that aims to modify behaviour through the use of positive and negative reinforcement (Skinner)6. Through operant conditioning, an individual makes an association between a behaviour and a consequence. For example an individual, who suffers embarrassment while speaking publicly, might then fear public speaking in the future and be less inclined to do so. By avoiding public speaking and therefore avoiding embarrassment, their avoidant behaviour is reinforced (negative reinforcement), leading to further avoidant behaviour. Whereas, an individual who is congratulated (positive reinforcement) while speaking publicly might regard this as an enjoyable experience and be more inclined to do so in the future.

Principle aims of CBT

As the name suggests, cognitive behavioural therapy uses both cognitive and behavioural techniques to modify how a person thinks and how they behave. In the cognitive component, the patient is taught to recognise how their thoughts affect their feelings and their behaviour. They are also shown how to spot negative, unhelpful, so-called “hot” thoughts and to question the evidence for these. The patient is also taught coping strategies for dealing with strong emotions. Through this process, CBT provides patients with a greater understanding of their thoughts and behaviours and prepares them with the knowledge to help modify unhelpful thoughts and behaviours.

The behavioural component of the treatment refers to helping the patient to devise a series of steps through which they can gradually experience the situations they have been avoiding. This may involve testing their beliefs about what will happen if they engage in activities or situations they have been avoiding. For example, a patient who believes: “if I leave the house, something terrible will happen” might be encouraged to make a prediction before leaving the house and then record whether the prediction came true. This allows the patient to build a bank of evidence, which helps them to reconsider irrational fears.

CBT is goal-oriented and problem focused, with an emphasis on current difficulties rather than on the past causes and symptoms. Through cognitive conceptualisation, goal-setting and behavioural modification, the patient learns to identify, evaluate and respond to dysfunctional thoughts and beliefs as well as a variety of coping mechanisms to help prevent relapse. CBT sessions are structured to increase the efficiency of treatment, improve learning, and focus therapeutic efforts on specific problems and potential solutions. Homework assignments are used to extend the patient’s efforts beyond the confines of the treatment session and to reinforce learning of CBT concepts.

Effectiveness

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews consistently report that CBT is an effective treatment for anxiety disorders 4, 7. The effects of CBT are most pronounced when undertaken in clinical trial settings, and compared with no treatment. Overall, CBT leads to remission in at least 50% of affected individuals. Of note, CBT can be delivered in many different ways including one-to-one with a therapist, group workshops, and self-help (either via a book or online) versions. Overall these different modes of delivery appear to be similarly effective.

Currently, relatively little is known about what factors predict outcome, and the biological mechanisms by which the treatment has its effect. Several patient characteristics seem to influence differential response. Numerous studies now report that greater baseline severity, comorbidity with other mental disorders, poor adherence with treatment, unemployment, lower educational attainment and intelligence, and interpersonal difficulties are associated with poorer treatment outcome for adults14–16. Similarly, greater baseline severity, comorbid psychopathology, and poor perseverance with treatment are associated with poorer outcomes in clinically anxious children11,12,18. Our group are exploring which genetic factors help in understanding CBT response.

There is a considerable amount of work underway to understand which individuals are most likely to need individual one-to-one treatment, and which patients will do equally well with a group or self-help approach. At present the majority of individuals treated with CBT in this country access it via their GP and the choice over mode of delivery is often influenced by practical issues such as waiting lists. In time, we hope research will be able to help people understand which form of the treatment is most likely to be effective for them.

This video provides a useful overview of CBT: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=214&v=9c_Bv_FBE-c

- Beck, J.S. (1964) Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond, New York: Guildford Press.

- Beck, A.T. (1976) Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders, New York: Penguin.

- Clark, D.A., and A.T. Beck. 2010. Cognitive Theory and Therapy of Anxiety and Depression: Convergence with Neurobiological Findings, Trends in Cognitive Sciences 14 (9): 418–24.

- Loerinc, A.G. et al. 2015. Response Rates for CBT for Anxiety Disorders: Need for Standardized Criteria, Clinical Psychology Review 42: 72–82.

- Polderman T.J.C. et al. Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nat Genet 2015; 47: 702–709

- McLeod, S.A. (2014). Classical conditioning. simplypsychology.org/classical-conditioning.html

- McLeod, S.A. (2015). Skinner – operant conditioning. simplypsychology.org/operant-conditioning.html

- Lynch, D., Laws, K., and McKenna, P. (2010). Cognitive behavioural therapy for major psychiatric disorder: Does it really work? A meta-analytic review of well-controlled trials. Psychological Medicine, 40, 9–24.

- Fenn K., and Byrne M. (2013) The key principles of cognitive behavioural therapy, InnovAiT, Vol 6, Issue 9, pp. 579 – 585

- Craske, M.G., and Stein M.B., 2016. Anxiety. The Lancet 388 (10063): 3048–59.

- Creswell, C., Waite P., and Cooper P.J. 2014. Assessment and Management of Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents. Archives of Disease in Childhood 99 (7): 674–78.

- Creswell, C., Waite P., 2016. “Recent Developments in the Treatment of Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents.”

- Hudson, J.L., et al. 2015. “Clinical Predictors of Response to Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy in Pediatric Anxiety Disorders: The Genes for Treatment (GxT) Study.” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 54 (6).

- Hudson, J.L., et al. 2013. “Predicting Outcomes Following Cognitive Behaviour Therapy in Child Anxiety Disorders: The Influence of Genetic, Demographic and Clinical Information.” J Child Psychol Psychiatry 54 (10)

- Newman MG, Llera SJ, Erickson TM, Przeworski A, Castonguay LG. Worry and generalized anxiety disorder: a review and theoretical synthesis of evidence on nature, etiology, mechanisms, and treatment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2013; 9: 275–297.

- Mojtabai R. Nonremission and time to remission among remitters in major depressive disorder: Revisiting STAR*D. Depress Anxiety 2017. doi:10.1002/da.22677.

- DeRubeis RJ, Cohen ZD, Forand NR, Fournier JC, Gelfand LA, Lorenzo-Luaces L. The Personalized Advantage Index: Translating Research on Prediction into Individualized Treatment Recommendations. A Demonstration. PLoS One 2014; 9: e83875.

- Hudson JL, Rapee RM, Lyneham HJ, McLellan LF, Wuthrich VM, Schniering CA. Comparing outcomes for children with different anxiety disorders following cognitive behavioural therapy. Behav Res Ther 2015; 72: 30–37.

- Wergeland GJH, Fjermestad KW, Marin CE, Bjelland I, Haugland BSM, Silverman WK et al. Predictors of treatment outcome in an effectiveness trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for children with anxiety disorders. Behav Res Ther 2016; 76: 1–12.

[…] range of evidence-based interventions, from self-help books and exercise to one-to-one sessions of cognitive behavioural therapy or counselling. As no single treatment will work for everyone, mental health researchers are […]