by Alan Read, Professor of Theatre; Lizzie Eger, Reader Emerita in Eighteenth-Century Literature; Rowan Boyson, Senior Lecturer in Eighteenth-Century Literature; Josh Davies, Lecturer in Medieval Literature; Clare Lees, Professor of Medieval Literature and History of the Language; and Ruth Padel, Poetry Fellow

Six members of the English Department reflect on three events which took place on a single day. The day was Tuesday 10 May 2016. But, as Alan Read suggests, the date itself is of little importance. The variety of connections and conversations remembered below is typical of what might be experienced, should a curious mind find themselves in College with an hour or two spare, a ready ear, and the patience to pinpoint the precious gems among the ineluctable events emails that come with an @kcl.ac.uk email address.

Diagonal Science

On days like this you might imagine you are in a University as it was always intended. Drifting between critical conversations, discussions, presentations, performances, poetry readings and parties, across all levels of the King’s Strand campus, the orthodoxies of subjects fall away, the expectations of expertise are confounded, the surprising connections rather than disciplinary distinctions prevail.

The early nineteenth century architecture of Robert Smirke, a distinguished architect with a somewhat unfortunate name, shimmers where it once stood solid, glimmers with the fireflies of thought and expression dancing across its static surfaces, a disorder of things you could say. Of course, the privilege to wander in this way might be rare, for students and staff alike, deadlines and demands still call. But when a college of colleagues and communities works like this the French Surrealist Roger Caillois would recognise it as a flaring of ‘Diagonal Science’.

Moving between each of those events on that day brings Caillois to mind. That is no bad thing when higher education is being stress tested to the max by marketisation and privatisation. This Day in the Life offers special succour.

Caillois had first developed his diagonal science in the journal Diogenes in 1959, seeking points of contact between scientists previously split by the silo-thinking of systematic separatism. Claudine Frank puts his mission beautifully, in her indispensable collection of his writings The Edge of Surrealism: ‘Charting what Caillois called “The shortcuts of nature”, diagonal science proposed an open series of new classifications based on creative, interdisciplinary, taxonomies.’ (2003, 49).

For me these shortcuts become desire paths, cutting between the sessions of a day that coincidentally find themselves programmed sequentially between 10 in the morning and 10 at night.

As I move between the various locations I realise, coming and going between periods and worlds, doors should be anathema to Universities worthy of their name.

As I move between the various locations I realise, coming and going between periods and worlds, doors should be anathema to Universities worthy of their name. We might need to keep floors, the practical significance of infrastructure is often underrated, but why so locked in to rote? Why so isolated? If the installation artist Gordon Matta Clark was still in town he would long ago have cut a spiral bore hole down through the King’s building to reveal the hidden associations within the honeycomb of cabinets, like treasures waiting to be revealed to the initiates and the innocents. Cemins de traverse of the mind, guided by the heart as well as the head, I administer my own exposure to these brilliant objects of study.

Of course, Caillois, being as belligerent as the rest of the Surrealists with whom he had an on off relationship, would have opposed any easy presumption that such an idea could be transported into ‘aesthetic practice’. He would have resisted my derive-like reverie on this day in my life. But he had come around to our way of thinking by 1970 when he presented a second manifesto on diagonal science in which the analogies and correspondences between fields that he sought were now open to ‘painters and poets’, which covers quite a few of us today as he really meant artists, and since Joseph Beuys we can be confident now ‘everyone is an artist’.

The work to be done was the keeping open of endless cross sections, ‘partial generalisations’ valuing dissymmetry over order, and of course implicitly attacking the dominant Structuralism of the day, not least of all his ethnographic whipping boy, Levi Strauss. In this Caillois was avowedly post-structuralist before structuralism as we tend to refer to it in the Academy had ever got underway. A pre-emptive strike against its binary logics you could say. Caillois was far more interested in concepts that were more difficult to fathom, he queered what went before with his concern for ‘abundance, play, ornament and decoration’. It would not be hard to imagine why I, as a performance specialist might be interested in such a take on the world.

There was nothing woolly about this, the words ‘rigorous verification’ would often cross Caillois’ lips (in French, touched by the burn of Gauloise). But well before Raymond Williams he was offering us a ‘structure of feelings’ in his work on a ‘science of sensations’. It was the conjectural scope of diagonal science that was to mark it out, and on that day, in each of those cabinets of wonder, given outlandish names like The Small Committee Room, aka K2.29, and The Council Room, aka K0.31, there was conjectural conjuring making all kinds of hard truth appear.

It might be time to hear from Caillois himself on this science, here he goes from his Poétique de Saint-John Perse of 1954; ‘The poet calls upon the world’s totality to establish fragile and tenuous homologies in the infinite variety of available phenomena. The hidden raison d’etre slowly appears, as the accumulating data increasingly betray and in the end bring to light the latent, middle term explaining the prodigious coalition’. (Frank, 343-347)

On that day ‘prodigious coalition’ felt about right for the accumulated connections, critical cathexis, that a place rather endearingly called King’s College could offer to the interested party or the passing diagonaler. How one might see it would be the cry? There was no Day Pass after all. Festival culture might have something to offer here with multiple stages and sophisticated cross-referencing between differently coloured wrist bands. Surely these diabolical lay lines of interest exist for the University only in your (my) imagination? Who has the right to follow this itinerary rather than the pre ordained one dictated by the capacious god of central timetabling? All students do for a start. They have rights to flow between such happenings at will, or at least as much will as their depleted budgets will allow before returning to other kinds of necessary work. That this day in the life represents unnecessary expenditure, of some effort at least, is the point.

But how to diagram such a thing to reveal its potential before that potential becomes its lost and latent force? I am posthumous, born after my father’s death, so of course I am predisposed to such flagging up of opportunity before it is too late. An anxiety of missing the main event has always been my modus operandi. When you have already missed one event of some significance for your future it rather focuses your attention on the game that follows. But posthumousness is by no means required as standard here. Perhaps we should encourage more traffic, more passports to foreign fields than our own interests, more acts of allegiance with those who question our most firmly held beliefs.

I returned to the Strand flooded with thought, saturated with senses. It was once a beach after all.

In a time of delirium, both then, and nor more so than now, Caillois sought a form of ‘rigorous deliria’ in his writing, influenced by Baudelaire as he was. To respond to this state he encouraged ‘more relay stations at every level’, ‘coordination points’ for comparing the spoils. I suppose this is what that day offered. Enough relay stations to power a damn of ideas and feelings by the end of it. I returned to the Strand flooded with thought, saturated with senses. It was once a beach after all.

Given all significant discoveries involve borrowing from one field to illuminate another, this should surely be the base expectation of a University that might be interested in education, never mind one or two more Nobel prizes. And not least of all what it might offer that exhausted figure of media fun: the interdisciplinary. One could not predict what would apply most wondrously to what, nor where. It is our responsibility, as was shown so generously on that day, to ask what the conditions of such compatibility of critical thought might generate beyond their own expectations when placed side by side with others of another coin.

A diagonal science is one which invites, Caillois would say ‘force’, but let’s be gentle, invites all of us to engage in dialogue. It seeks to make out what Caillois called ‘single legislation uniting scattered and seemingly unrelated phenomena’. Here, deciphering latent complicities and neglected correlations, the work is presumed to reach beyond itself to something that is more than its various parts. I will not suggest in these dangerous times what such aspirations might be. But given that Universities commonly plead their relevance to ‘increasingly complex worlds’ it might be that A Day in the Life points to one way in which such complexities can be taken seriously.

We might begin by noticing what such days do by existing at all. They represent the impossibility, the anxiety and the experience of knowing what one always already knew, that there is just too much to do, too much to know and a finite time to do it in.

We might begin by noticing what such days do by existing at all. They represent the impossibility, the anxiety and the experience of knowing what one always already knew, that there is just too much to do, too much to know and a finite time to do it in. But take a look at the date of the day in our life. If you cannot answer what it was that made that day a special one, or a remarkable one, a day in your life, then it might be that by simply weaving through these waves of thought something other would have happened. That might not necessarily be a bad thing.

It is not what is around the corner that might be the point, rather the continuous presence of something here and now, if we could just see it and listen to it and talk back to it. For this Day in the Life, there are countless others if we look carefully. It is business as usual at King’s. But beyond these parallel sessions it is oblique thinking that is all the more necessary today. Universities might recognise that everything of cultural disciplinary interest in the last half century, from queer theory, post colonial study, post humanist discourse through to object ontologies, cyborg thinking and trans-disciplinarity, has been oblique, diagonal in nature.

Just because our architects tended to build in parallel lines should not limit our appetite for the diagonal now. Take a short cut of your own between the posts on this site, between the contributions to this essay, between this site and the estates of our college, and ask yourself not what your University has done for you, but what you have done diagonally for your university.

Does diagonal science matter? Well, I read the news today, oh boy …

Alan Read

The Order of Things: Reflecting on Foucault and the Humanities at King’s (Part I) 10am-3:30pm

Foucault’s Order of Things is one of those rare texts that remain revelatory however many times you read it. The book’s extraordinary opening passage, in which Foucault guides the reader, slow-motion, through the visual language of Velasquez’s Las Meninas, is always startling to me in its combination of raw, apparent simplicity and sinuous sophistication. Meaning is made by a process of layered accretion; words are knitted together through a process of instinct and intention, a series of gestures and perspectives that have immediate affinity with the daubs of a painter’s brush. Like Velazquez himself, Foucault suspends the reader in an experience of inter-subjectivity that is mysterious, urgent, dislocating ‑ yet somehow also affirming. The materiality of a painted image is given centre-stage in an invigorating history of ideas.

Rowan Boyson’s inspired idea of inviting scholars from across the School of Humanities to reflect upon Foucault’s text together provided an opportunity to exchange ideas and make connections across departmental boundaries. As in Foucault’s text, the dialogue between words and things created a positive tension and demanded that we immerse ourselves in the practice, as well as the theory, of knowing. Foucault’s Order of Things celebrates the full complexity of any attempt to define a history of epistemology, placing the emphasis on process, or as Nikolas Rose put it during the workshop, ‘what knowing involves.’

Lizzie Eger

The Order of Things: Reflecting on Foucault and the Humanities at King’s (Part II)

The idea came, as these things often do, in an accidental way: I was writing a footnote, and had to look up the original publication date of Foucault’s Les mots et les choses. I duly noted ‘1966’, and the date suddenly struck me as a long time ago, indeed, a half century past.

I mused on the fact that ‘theory’ is often still thought of as the contemporary edge of academic research, yet it is increasingly historical itself.

Some academics believe that merely ‘fashionable’ theoretical interventions have now been superseded by a more rigorous, straightforwardly historical approach to our materials. Yet, participating in an Enlightenment roundtable for the King’s MA in Eighteenth-Century Studies a while ago, it struck me how deeply all current approaches to our period are still embedded in the frameworks laid out by Foucault. For instance, the idea of interdisciplinarity has not gone away, and one can see it as emerging partly from Foucault’s idea that diverse forms of knowledge generated in one ‘episteme’ were more similar than those emerging from single disciplines over longer time periods.

So I began planning a small interdisciplinary event on the legacy of Foucault’s key work, based in our Centre for Enlightenment Studies, inviting King’s researchers in Arts and Humanities to participate. Speakers included Elizabeth Eger, Matthew Head, James Morland, Daniel Orrells, Sanja Perovic, Nikolas Rose, Andrea Schatz, Adam Sutcliffe, William Tullett, Neil Vickers, Jon Wilson and myself. As several people were quick to point out, focusing on The Order of Things and the humanities carried a heavy latent irony, due to Foucault’s explicit anti-humanism in the book. But the decision proved productive of one of the day’s most vigorous debates, generated by the involvement of sociologist and eminent Foucauldian, Nikolas Rose, on the future of humanism in the wake of neuroscience and the anthropocene. Other topics we discussed included: Mozart’s taxonomic approach to music, eighteenth-century antiquarian practices, Foucault and Said’s orientalism, the history of the senses, eighteenth-century vitalism, Foucault and his connection (or rather lack of connection) to the French Revolution, and the possibility of a Foucauldian perspective on transgender rights.

The discussions were exciting and intellectually appetitive. But I was left with a few nagging questions about the very presuppositions of my own event. First of all: what are the risks of returning endlessly to super-theorists like Foucault, and replicating what Alan Read calls the hierarchy of citation? Second: what is behind the current academic culture of ‘anniversarization’ (witnessed on a grand scale in King’s’ Shakespeare 400)? Later, a Swiss colleague pointed me to another classic text, Pierre Nora’s ‘Between Memory and History: Les lieux de mémoires’ (1989). As Nora put it, lieux de mémoire ‘originate with the sense that there is no spontaneous memory, that we must deliberately create archives, maintain anniversaries, organize celebrations, pronounce eulogies, and notarize bills because such activities no longer occur naturally’. Deploying a metaphor very much like Foucault’s final image in The Order of Things, Nora notes that these anxious, defensive sites of memory are detached ‘moments of history’ ‘like shells on the shore when the sea of living memory has receded.’

Whether or not one agrees with Nora’s nostalgic view of a long-gone state of living memory, one might agree that academic anniversaries speak to a certain anxiety about the huge ocean of (often un-read) research in which we now swim. To me the event memorializing Foucault’s powerful and original 1966 book had something to do with finding an anchor by which the large and diverse research community at King’s could hold itself steady, together, for a day.

Rowan Boyson

A Workshop on Creative Medieval and Translation Practices – A Think-in and Thank you! 4pm-6pm

Over the past few years King’s early medievalists, Josh Davies and Clare Lees, have worked on a number of projects that have explored meeting points between early medieval culture and contemporary artistic practice. We aim to identify, explore and creatively develop the many surprising connections between the earliest centuries of artistic production in Britain and Ireland and our own modern and contemporary centuries. In cutting across disciplinary practices more conventionally kept apart (medieval studies and modern studies, for example), we have created communities of research, learning and teaching that work beyond our more familiar curriculum offers.

We have developed our work with undergraduates in their second and third years within and without the classroom, as well as with MA students, doctoral and post-doctoral students. We have brought artists, curators, and medievalists from other universities into these on-going creative conversations where our ideas, learning and interests are shared non-hierarchically. We have participated in salons at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, for example, as well as in workshops on teaching and translating at Brasenose College, Oxford, thanks to the interests we share with Helen Brookman, Director of Liberal Arts and Pro-Vice-Dean for Innovation in Education in the Faculty of Arts and Humanities at King’s.

In the academic year 2014-15, we worked in particular with Caroline Bergvall, Forster & Heighes, and staff and students from King’s and Royal Holloway, University of London, on a collaborative translation and performance of the Old English Riming Poem, celebrated as one of the most difficult early medieval poems to translate. This resulted in a public performance in May 2015. In the academic year, 2015-16, we consolidated and developed our relationships and methodologies by participating in workshops on creative translation, medieval studies and contemporary performance at, for example, Metal in Southend on Caroline Bergvall’s new project Raga Dawn, the London Anglo-Saxon Studies Symposium (an annual event for all those interested in early medieval studies), and at King’s. A number of the undergraduates who participated in these events were set to graduate in July 2015, but before they left us we wanted to bring everyone together for one final event to thank them and to participate in a public ‘think in’.

‘Creative Medieval and Translation Practices’ brought together a number of our collaborators and other interested staff and students from King’s, Royal Holloway and Oxford, in order to celebrate and reflect on the work we had already done together and to plot some lines of future enquiry. The workshop was structured around three presentations: the poet Hillary Davies, then a Royal Literary Fund Fellow at King’s, addressed her interest in the twentieth-century Anglo-Welsh poet David Jones’, medieval culture, and the historical research that informs his poetry – and hers; Carl Kears, who recently completed his PhD at King’s in Old English poetry and currently teaches in the English Department, talked about his work in the Eric Mottram Archive at King’s and the history of creative engagement with Old English he has discovered in the archive of this distinguished scholar of American Studies; and Caroline Bergvall reflected on our work together and on the centrality of research to creative practice. There was also cake!

Our collaborative enquiry into multi-disciplinary arts practice has identified the importance of further archival research into how early medieval culture informs modern and contemporary arts and scholarship.

Our collaborative enquiry into multi-disciplinary arts practice has identified the importance of further archival research into how early medieval culture informs modern and contemporary arts and scholarship. Equally importantly, it has underlined the necessity for participatory projects in the future that will continue to translate the cultural relationship between the past and the present into new practices of learning, teaching, and researching.

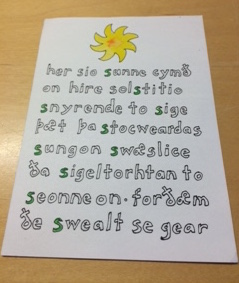

The image we have included here is a greetings card made to mark the winter solstice by the scholar Bill Griffiths and sent to Eric Mottram in the winter of 1984, discovered by Carl Kears in the Mottram Archive. It is written in Old English but expresses hope for the future and provides a rich example of the long history of creative medieval studies.

And so, finally, we again thank all King’s early medievalists who have inspired such creative knowledge of early English literary culture.

Clare Lees and Josh Davies

Cosmo Davenport-Hines Poetry Prize. 6:30pm-10pm

I love that the end of year party at King’s is built around poetry. That says it all. From an obligatory first year course on Reading Poetry, and a system of basing the relationship of personal tutees with their tutor, for the whole three years of undergraduate life, on seminars for Reading Poetry, to the fantastic spread of modules on different sorts of poetry from multiple perspectives, poetry is at the heart of the whole experience of English at King’s. Declan Ryan and I, teaching our “Creative Writing (Poetry)” module, have the luxury of knowing that our students are working with many different areas of poetry all the time.

I also love the party because it’s great to be in a room with a lot of students feeling so cathartically free. They have mostly stayed up all night (they shouldn’t, I ask them not to, please submit your stuff a day early, but of course they do) and are in a state of exalted top-of-the-world exhaustion which gives the party a special energy. This year I talked to so many students who said the third year brought everything together, and the whole course just got better each year, which was the icing on the cake.

Then we heard the winners read their poems. Megha Harish (BA Liberal Arts) read her poem ‘Inheritance’, which was lovely to hear; we were sorry that her co-Third Prize winner Valeria Marcon (First year English) couldn’t be there, as we were particularly interested to hear how she would read her inventive, wildly modernist poem, ‘Poem One’. Will Sharp (doing an MPhil in the Department of Philosophy) read ‘Rue Pajole at Via Borghesano Lucchese’: a beautifully controlled lyric, with the imagery mediating between abstract and concrete. There had been some discussion among the judges about what exactly a vector was and did it matter that this might not be clear? So I was fascinated to discover that this poet was a philosopher, whose business seems to me to be precisely going between abstract and concrete.

Jamie Foo (First year English) read her winning poem ‘Time Difference’, which won all hearts with its reference to Pat Palmer’s unique and much loved module “Language in Time”. The poem also spoke to the experience of going abroad, away from home to study in another language, which opens out more broadly to every student’s experience of being away from home. But of course, in the judges’ discussions, we didn’t talk about those aspects of it. It is not a poem’s subject matter but how it says it, that counts. We loved this poem’s beautiful control (within a very emotive context) of conversational tone, and the way it communicates so much so apparently effortlessly: and we also appreciated what it left unsaid.

At the party though, not much else was left unsaid. Jamie Foo had to disappear, she had an exam the next day, but it was great to see students I had taught over the last two years so delighted to have come through the submitting ordeal, happy to look back over their courses, and looking forward to a brave new world ahead.

The prize winning poems are available to read and enjoy here.

Ruth Padel

You might also enjoy The Virtues of Slow Scholarship.

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and not those of the English Department, nor King’s College London.