by Professor Alan Read

In the 1980s Alan was director of Rotherhithe Theatre Workshop, a neighbourhood theatre based in the Docklands area of South East London, in the 1990s he worked as a freelance writer in Barcelona and was Director of Talks at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, and from 1997-2006 he was Professor of Theatre at Roehampton University where he directed a five year AHRC research funded programme on performance, architecture and location exploring theatre and public ceremonial in rational housing blocks and council estates.

The Dark Theatre was written as a critical response to my first book Theatre & Everyday Life (Routledge, 1993). This book mimicks the ambitions and two-part structure of that earlier work but takes stock of the intervening quarter-century turn towards financialization and precarity in Western Europe, exploring a ‘general economy of performance’ by way of response to these capitalized conditions. The Dark Theatre is not an updating of the source work but instead engages with questions of community, ecology, and what I call ‘cultural cruelty’ as evidenced in practices ranging from theatrical acts to legal processes.

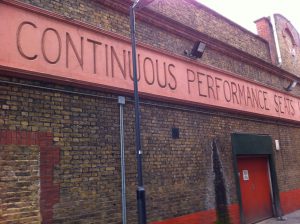

The first half of the book is dedicated to examining the conditions of ‘expulsion’ in 1991 that preceded the closure of the theatre that I directed in London’s Docklands through the 1980s (Rotherhithe Theatre Workshop). Through economic, ethnographic, and political analyses I examine the setting for the enclosure, privatization and rapid gentrification of the theatre’s neighbourhood; the theatre’s eventual bankrupting and enforced closure (hence the title of the book which refers to a closed and abandoned theatre, not theatre practice conducted in chiaroscuro gloom); and the site’s subsequent life over a quarter of a century as a prime real-estate location.

The questions this detailed local history raises for conceptions of performance and its politics, the relations between community and immunity in theatrical analysis, and critical conjunctions of social reproduction and the domestic economy, are the subject matter of a book with a gloomy title.

To start with I characterize the intervening 25 years since the closure of Rotherhithe Theatre Workshop as something rather more dystopian than my previous prediction. In Theatre & Everyday Life I prognosticated there would be an ‘eruption of the audience’ into all fields previously policed by cultural gatekeepers through my somewhat romantic conception of ‘lay theatre’. Now I posit the inundation of the public realm with what I call ‘the ‘dictatorship of the performatariat’.

I date this cultural formation from The Family (1974) on UK TV. The show followed the everyday tribulations of a family in Reading in South East England and inadvertently turned them into the object of adulation and admonition – and the target for hate mail in an uncanny foreshadowing of recent fly-on-the-wall documentary shaming-dynamics. I then set this example in its historical continuum towards the ubiquity of social media platforms today, a dynamic somewhere between democratization and demonisation that Antonio Gramsci might have described as ‘the morbid’ symptoms’ of an interregnum dedicated to the petty cruelties of the commentariat.

This ‘communicative individualism’ (from Jodi Dean) sets the foreground scene (in a mirroring of Plato’s Cave) against which any kind of theatrical labour takes on various kinds of background rearrangement (as in the unseen stagehands administering the puppets in Plato’s fable). Gone are the days, I suggest in The Dark Theatre, when one might have imagined the liveness of performance to be able to sustain any distinctive prioritization over this virtual public realm for its peculiarly manual, perhaps sometimes heavy-handed acts (though by the Epilogue to the book, ‘The Return of the Loss Adjustor’, I do offer some specific ways in which performance might be expected to illuminate the shady contours of this obscure scene).

In The Dark Theatre this adjustment is not perceived as a demeaning ‘relegation’, unless as I questioned previously in Theatre & Everyday Life one wishes to sustain an outmoded and privileged status for performance amongst all other possible arts of making do, or, as proposed rather more radically in The Dark Theatre, simply buy in to the ubiquity of cultural cruelty for the sake of its own currencies of collateral profit.

The second part of The Dark Theatre is written up from the field notes of a sequence of international performances that like a ‘fire sale’ lay out those things left for acquisition after the bankruptcies described in Part One, and by the end of the book, at Battersea Arts Centre and Grenfell Tower, ask what is left after fire itself requires activism to now work amongst the ashes. The second part of The Dark Theatre then follows the broad ecological categories of association between ‘Nature, Theatre and Culture’ first tried out in Theatre & Everyday Life in 1993 (some years before environmental concerns were anything like as prominent in performance study). Only now, through a sequence of linked case studies of performances across Europe, I account for the limit conditions the pressing concerns of ‘cheap natures’ (Jason Moore), the ‘microeconomic mode’ (Jane Elliot) and ‘the last human venue’ (Alan Read) have set theatrical practices seeking the contemporary ‘real’.

The geographically broader theatrical concerns of the second part of the book are tethered to and read back through the first three chapters. I draw directly upon the narrative of bankruptcy there, for instance, as well as the peculiar historical place London Docklands has had in the emergence and pervasiveness of the consequences of empire, the exploitation of those ‘cheap natures’ that sustained the capitalist project, and the neo-liberal co-option of the corporeal and psychic realm that laid some of the ground work for the pathological conditions being experienced as standard in advanced economies in Western Europe today.

The book ends where it started in 1991, a theatre capital called London in which Capital has been busy at work, where legal processes would belatedly appear to have caught up with a ‘culture class’ and their special pleading for the continued privileges of something (without further explanation) they call ‘Art’. The two concluding chapters that move between the orchestra pit of the Royal Opera House, the burnt out Battersea Arts Centre, and the differently burnt Grenfell Tower, concern evidence of the damages sustained by those who find themselves on the wrong side of a cultural divide, apparently divorced from the protections afforded other industrial workers, and considers the kinds of compensation that might be afforded those tasked to entertain us through what Bertolt Brecht might have called these ‘bad new days’. This conclusion to The Dark Theatre makes explicit the links between the political analysis of the theatrical imaginations of such ‘new days’ with those rather older ones with which the book began through the 1980s.

The Dark Theatre is an unusual academic project in that it reflects, articulates, and critically addresses my own direct experience of a decade of theatre-making through the 1980s (unlike theorists who tend, perhaps inevitably, to lean on others’ practiced work). More than this, it returns to that cultural crime scene twenty five years after its obliteration by the forces of Capital to ask what was learnt (by myself and others) from the intervening temporalities between that ‘now’ past, and the present becoming a future fact.

What I describe as the ‘disappointment’ of the Dark Theatre, working now for 25 years beyond the closure of a shared theatre project, in its sorry wake you could say, has to – in my view unfashionably -return the question of community to the foreground for robust reconsideration. While suffering secondary status in political and cultural theory when placed alongside questions of equality, freedom, justice, and rights, ‘community’ appears for many to have become so contested as to be not worth the trouble. In the book I make it clear why this is not the case for me, nor those I choose to work alongside in activism of various kinds, nor does it for a moment becalm the urgent politics central to the writing of The Dark Theatre.

This is a necessary and rather overdue response to the long-running, publicly rehearsed and repeated claim from my colleague Janelle Reinelt, that my recent work of the last decade, as evidenced by my last three monographs at least, has somehow surrendered its political principles for some kind of ‘post-politics’ quietude of political submissiveness. On the contrary, I suggest in The Dark Theatre, each of my recent projects whether published or practiced on the street, conducted within labour unions or environmental groups, played out amongst publics, or worked within institutions, has successively attempted to demonstrate and articulate why and how a critical commitment to politics is central to all I practice and write amongst others.

But what if when ‘the curtain falls at last’ there is a requirement to somehow continue?

To open his celebrated novel Revolutionary Road Richard Yates writes with poignant foreshadowing of an amateur production by the Laurel Players in Connecticut that ends in fiasco: ‘When the curtain fell at last it was an act of mercy’. But what if when ‘the curtain falls at last’ there is a requirement to somehow continue? An expectation that to fulfil some kind of promise to those with whom one has worked in the theatre, something more might be said and done? The Dark Theatre is written out of just such disappointment turned to unlikely hope, a state of gloaming through which nothing so much as an image, but what Georges Bataille would have identified as a ‘twinkling’ of illumination, might appear. Or, as Antonio Gramsci presciently wrote of his time, but now especially ours: ‘Entering and exiting. These two words should be abolished. One does not enter or exit: one continues.’ (Avanti!, 11 September 1917).

The Dark Theatre was written in the two years immediately following the Grenfell Tower fire and was set by Wearset for Routledge in the galleys in the weeks prior to the emergence of the Covid-19 Pandemic in the UK in February 2020. There is only one reference to Covid-19 in the book, in the Index: ‘post-pandemic/pre-pandemic: see The Dark Theatre as symptomatic of inter-pandemic writing 1-320.’ Given theatre’s life during the precise four decades the book covers has always necessarily be in repressed dialogue with the ongoing devastation of the HIV AIDS pandemic, there is no room for any fatuous presumption of a ‘post pandemic’ mode now.

If you would like free access to a chapter on ‘Cultural Cruelty’ from The Dark Theatre it is available here for a modest cut of your personal data.

Twitter: @readalanread

Wiki: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alan_Read_(writer)

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.

You may also like to read:

- WOMEN ARE BEING EXCLUDED FROM THE STAGE. IT’S TIME FOR QUOTAS.

- PERFORMANCE/MUSEUMS/PRACTICE

- SHAKESPEARE AT WAR