PhD researcher Lizzie Hibbert reflects on Sam Mendes’s First World War epic 1917. Please note: this piece contains spoilers!

Sam Mendes’s 1917 (2019) is as much a film about time as it is about war. The first indication of this comes in the film’s trailer, which is set to a soundtrack of ticking clocks. It opens on a wide shot of an un-helmeted British soldier running perpendicular to advancing troops towards the camera. The reedy ‘tick… tock…’ of a watch is just audible beneath ominous music and accelerating bootsteps. Suddenly we are underground by torchlight, and the ticking has transformed into the weighty, echoing hands of a pendulum clock. There is a split second of silence and then an explosion.

Another watch begins to tick. This time we can also hear the escapement mechanism clicking at twice the speed of the second hand, so that ‘tick… tock…’ becomes ‘tick tick tick tick tick.’ Now a grave-faced, candle-lit General is explaining the film’s premise to our two protagonists, whose skeletal faces flicker in the flames:

You have a brother in the Second Battalion. […] They’re walking into a trap. Your orders are to deliver a message calling off the attack. If you don’t, we will lose sixteen hundred men, your brother among them.

The boots begin again in rhythm with the ticking. The word ‘TIME’ flashes up on a black background with the film’s two protagonists inside the ‘I’ and the ‘M.’ There are short, disorienting clips of disconnected action, then ‘IS’, ‘THE’, and ‘ENEMY.’ As the music swells and the clock sounds amplify, we hear the General’s instructions again: “if you fail, it will be a massacre. Good luck.”

1917 works because it is essentially a thriller. Its plot is a simple race against time, departing little from the outline given in the trailer. As a setting, the First World War lends itself well to a plot which revolves around timing. Time looms large in accounts of war on the Western Front, a major source of psychological anxiety. As the imagist poet Richard Aldington, who was conscripted in 1916, wrote in his novel Death of a Hero (1929), ‘the time element was of extreme importance during the war years.’

1917 underscores the importance of ‘the time element’ to its protagonists Lance Corporals Blake and Schofield (Dean-Charles Chapman and George Mackay) by drawing careful visual attention to their wristwatches. While the two are being led by their sergeant to receive orders from the General, the huge, white watch faces on their left wrists stand in sharp contrast to their own grey faces and all-khaki attire. As they approach the General’s dugout the Sergeant turns and taps his watch. “In your own time, gentlemen,” he barks.

These wristwatches would have been the first those characters had ever worn. Prior to 1914, while some wealthy women wore ‘wristlets’ or ‘bracelet watches,’ these were considered jewellery. Men, if they wore watches at all, carried pocket watches. War on the Western Front was the first in British military history whose battles were conducted by generals in remote field headquarters away from the fighting, which made temporal uniformity and synchronisation a military necessity. As a result, in 1916 the British and French Armies began issuing ‘trench watches’ to certain personnel (notably signallers and telegraphers) and instructed infantrymen to purchase their own.

In one 1916 official portrait by the British Army photographer Ernest Brooks, Field Marshal Haig’s left hand is laid flat on the desk in front of him, with a state-of-the-art wristwatch poking prominently out of the cuff of his jacket. At this stage of the war, as stalemate became increasingly insupportable, and the need to gain ground through mass offensive action more acute, Army Command began to place increasing emphasis on accurate timekeeping.

In 1917 Lance Corporal Schofield is acutely aware of the importance of paying close attention to time. He checks his watch as soon as he emerges from the General’s dugout, telling Blake that they should discuss their plans for precisely “a minute.” Blake snaps “why?” and jogs off clumsily, struggling to make out his own watch as he goes. Schofield holds his watch face steady with his right hand and calculates that the journey will take them eight hours. As the two move along the communications trenches leading from the reserve line to the front, each brings his left hand across his chest to support the rifle strap on his right shoulder, and their two white watch faces are again suspended in the centre of the frame. The audience begins counting down the time they have left to reach their objective.

But, as Blake and Schofield soon learn, keeping accurate time is impossible in the chaos of war. At the point of the front line where they are to cross into No Man’s Land, the commanding officer Lieutenant Leslie (Andrew Scott) greets them with “Settle a bet— what day is it?” When Schofield replies that it is Friday Leslie raises his eyebrows in pantomimed surprise: “Friday? Well, well, well, we’re none of us right. This idiot thought it was Tuesday.”

The journey does not go smoothly. As long as they are moving forwards, Blake and Schofield’s left hands are lowered, supporting their rifles, so their jacket cuffs cover their wrists. But every time they meet an obstacle which threatens to delay them, their wristwatches reappear to taunt them. The first instance of this occurs almost as soon as they have entered No Man’s Land, when Schofield cuts his left hand on barbed wire. He stops for a few seconds, wincing, and as he holds his bloody hand in front of his face his sleeve slips down to reveal his watch to the audience. As the journey progresses, Schofield is repeatedly slowed down by problems with his left hand, and after almost every setback the two stop to drink water or to run their hands through their hair with anguish. In every one of these instances their watches are unveiled, reminding the audience repeatedly of how little time the two men have left.

The biggest pause in the film’s forward momentum is Lance Corporal Blake’s death around halfway through the film. Schofield cradles Blake’s head in the crook of his arm as he bleeds, and its weight pushes his sleeve up almost to his elbow, so that his watch face rests in the centre of the frame next to Blake’s face. As he is dying, Blake lays his left hand across his chest. Close up, we see that, unlike Schofield’s, his watch-face is covered by a heavy metal shrapnel guard to protect it from shattering.

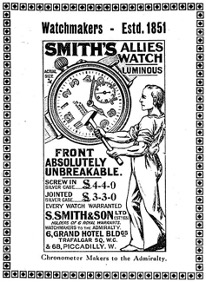

That Blake’s wristwatch is better protected than he is is a bitter joke. Trench watches were marketed as protective instruments, as in one 1917 advertisement by London watchmaker S. Smith & Son for the ‘Smith’s Allies Watch,’ which describes it as ‘ABSOLUTELY UNBREAKABLE‘ alongside an image of a rugged man with his sleeves rolled up to reveal impossibly muscled forearms. The pun on ‘front’ underscores the implication that an ‘unbreakable’ timepiece makes its wearer equally ‘unbreakable’ in battle. For Blake, this proves pitifully false.

Ford Madox Ford, who fought in the Somme and at Ypres, wrote in his 1933 memoir Return to Yesterday, that ‘everyone who took physical part in the war’ had come home with the knowledge that ‘beneath Ordered Life itself was stretched, the merest of film, with, beneath it, the abysses of Chaos.’ The Army introduced wristwatches as a means of imposing order on an increasingly chaotic war, yet, as Schofield learns, they provided merely the illusion of control. Schofield has almost reached the Second (Devons) Battalion when he is knocked out for an indeterminate number of hours by a blow which also smashes his wristwatch. When he awakes, he has no idea what time it is or whether he can reach the Second in time. But then, neither he nor Blake, nor even the General, had ever been sure they would make it.

Once Schofield has completed his mission we never see his wristwatch again. He and Lieutenant Blake shake right hands, his left hanging loose by his side. When he sits beneath a tree and holds up a photograph of his wife and daughters with his left hand, his cuff stays resolutely down over his wrist. On the back of the photograph is written ‘Come home to us x.’ Neither he nor the audience knows whether he will ever make it home, and he has abandoned the illusion that it is in his control. All he can do is keep going.

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.

You may also like to read: