To celebrate the launch of the new Queer@King’s goes to Church series, in collaboration with KCL Chaplaincy, Victoria Carroll reflects on the sacrilegious artwork and drag performance of Jerome Caja (pronounced Chi-a), an important figure in the queer arts scene that flourished in early 1990s San Francisco.

To find out more about the Queer@King’s takeover series at the Strand Chapel, sign up the Q@K’s newsletter or book a spot at the event kick off on Thursday January 30th with a drag performance by Virgin Xtravaganzah followed by a Q&A.

“Through the strict instruction of our Lord I have [an] earnest desire, passion, even a little heat, to see every person, place and thing much much more glamourous. And so I call upon the most sacred lipstick, the blessed eye shadow, and the most high eyeliner, to create Icons for the girlieus [sic] of today, or anyone else who happens to be into that sort of trash. And in closing, my brothers and sisters and things, if you take offence at something, just try not to look at it.”

‘Letter from Jerome Caja to the San Fransicoians [sic] (and any other hapless victim who happens to gaze upon this page)’ (1989). The Jerome Caja papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institute, Washington D.C.

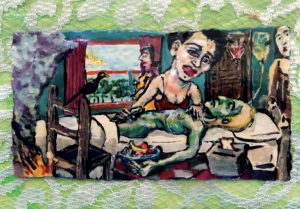

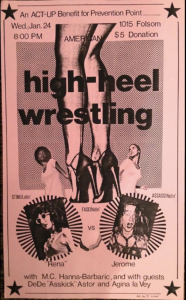

Jerome Caja flickers in various constellations of queerness that converge in San Francisco in the early 1990s. He is elusive, unfixed, difficult to plot: punk, drag queen, peripheral AIDS activist, Imperial Court Empress, go-go boy-cum-performance artist at the infamous Club Uranus, high-heel wrestler, mild S&M enthusiast (a regular at the Folsom Street Fair), acclaimed painter, beloved member of a queer generation lost to AIDS. As his close friend and fellow artist Nayland Blake attests, he is “a figure that doesn’t really translate,”[1] partly because he was so impishly dismissive of unwavering allegiance to any tribe. Jerome is an apparition that could only manifest in the Bay Area at the end of the twentieth century, before the onslaught of gentrification and the mainstreaming of LGBT interests in the U.S. Yet he continues to delight and offend in equal measure. He is both relic and heirloom.

Jerome – his preferred moniker – was born in 1958 in Cleveland, Ohio into a large and devoutly Catholic family, the third of eleven sons. Trained as an artist, he relocated to San Francisco in the mid-1980s where he lived until his death from AIDS-related complications in 1995. Jerome immediately became a fixture of the city’s vibrant queer and drag scenes, garnering mainstream attention from the gay press as well as participating in more alternative forms of queer cultural production and activism. (He becomes a regular feature on the cable access Queer TV program ‘Electric City’, the ad-hoc media arm of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) in San Francisco, working to explode false narratives around HIV/AIDS.) He careens between the centre and the margins of queer culture at this time, tottering on stilettos with busted heels, crashing to the floor at regular intervals, legs splayed and beaming smile intact. He gains some notoriety as an artist – today his work is held in the collections of preeminent cultural institutions, such as the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Smithsonian Institute’s Archives of American Art – yet would often shun collectors, preferring to hock his creations in the legendary South of Market Street gay bars (The Stud, The EndUp, Screw) or give them away to friends and acquaintances. Collectors who did make it into his inner sanctum had to endure a lengthy “beauty pageant” in which Jerome’s vast collection of work was trotted out for inspection and potential buyers were made to select their “winner.”

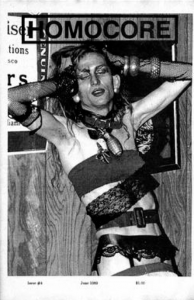

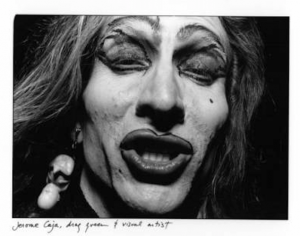

Jerome had an equally irreverent and anarchistic relationship to gender, flipping haphazardly between pronouns and genderqueer personas. “If she were alive today, she would drive the pronoun police crazy,” Justin Vivian Bond insists, “because she didn’t give a shit.”[2] It is hardly surprising, then, that Jerome became a darling of the West Coast queercore punk movement, which advocated gender fluidity and the militant rejection of gay and lesbian assimilation into a vapid consumer het-culture. His deconstructed ‘post-apocalyptic’ drag aesthetic reflected this ethos – although it is doubtful that Jerome would have conformed to any ideology, no matter how radical. Nevertheless, he was not afraid to expose the violence that always already attends the construction of gender – of producing and maintaining coherent, legible and differentiated genders that, when performed correctly, accrue value – or the labour of dragging up. He flagrantly transgressed the regulatory codes of feminine beauty, drag “realness,” and high camp glamour with gleeful abandon. His preferred look was often grotesque: a face caked with white make-up, illuminating rather than concealing flawed skin; garish lipstick and eyeliner applied outside of the lines; unkempt blond hair still playing host to rollers; black lacy lingerie scarred with ladders (the aftermath of a violent encounter, of rough contact). Like the used condom earrings he was infamous for sporting, his presentation of a stylized femininity did not seek to hide or abject the action that dictates its legitimacy.

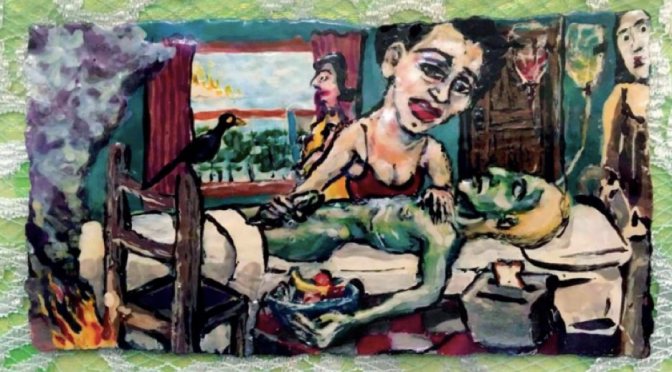

Jerome is perhaps most legible in the contemporary moment as an audacious visual artist known for his erotic, whimsical miniatures created using cosmetics and reconstituted trash (bottle tops, pistachio shells, cigarette butts, plastic tip trays) as well as human detritus: toenail clippings, hair, the bloody bandage from an HIV puncture test, the cremated remains of his close friend Charles Sexton, dead from AIDS. (“I wanted to make her work for her living,” Jerome once quipped, never one to give in to sentiment.) In Jerome’s oeuvre things become sacred precisely because they are, or are considered to be, profane: the discarded residue of disorderly queer bodies. His subject matter is just as unconventional, a heady concoction of gay sex, bodily functions, Catholic iconography, clowns and smiley faces, drag queens, fried eggs and bacon rashers, and high art references (shades of Hieronymus Bosch’s monstrous altarpieces, Goya’s ‘Black Paintings’, Egon Schiele’s broken-down, sensual nudes), all rendered in lipstick, mascara, and nail polish: the cheap tools of his drag labour transubstantiated into art, acquiring value in the process.

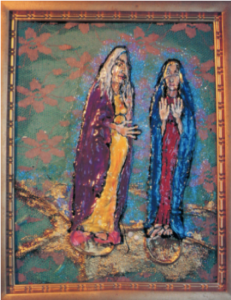

These ‘cosmetic miracles’ – as he fondly anointed them – revel in the inherent queerness of Catholic doctrine and ritual: women that turn into men (in order to enter heaven); reproduction without heterosexual contact (the inception of Christ); celibacy in cloistered homosocial space; the transcendence of binary oppositions (the Holy Trinity), the forging of bonds through the ingestion of Christ’s bodily fluids in the Eucharist, a form of contractible kinship that resonated in the early years of the AIDS epidemic. In Mister Sister (1993) a nun lifts her habit to reveal a cock. In The Visitation (1994) Jerome paints himself as an overenthusiastic Mary, advancing on a wary Elizabeth, both figures enclosed in used condoms, the rims binding their feet like inverse halos. In The Last Hand Job (1993) a drag queen delivers the ‘last rites’ to a friend dying of AIDS, perhaps Jerome himself – the service she renders is not eternal salvation, however, but sexual succour (a right even in the middle of a plague) and care that would traditionally be outsourced to the heteronormative family or the state.

Like their creator, these works are complex, ambiguous, witty, confrontational, and often unutterably tragic. They are not for the squeamish or the easily affronted. But as Jerome instructs in his ‘Letter to the San Fransicoians,’ “if you take offence at something, just try not to look at it.”

Postscript: If you do want to look at Jerome’s work you can do so via The Jerome Project, a “multi-platform art history project to preserve, protect, and further the artistic legacy of the late Jerome Caja.”

[1] Oral history interview with Nayland Blake, 2016 November 25-26. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[2] Justin Vivian Bond, Jerome Caja: Nayland Blake and Justin Vivian Bond in conversation (New York: Visual AIDS, 2019), 17.

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.

You may also like to read: