by Lawrence Warner, Reader in Medieval English, KCL

Dr Warner’s third monograph, Chaucer’s Scribes: Medieval Textual Production, 1384-1432, was published by Cambridge University Press in 2018. He is also undertaking a new critical edition of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. He is recipient of the 2016 Beatrice White Prize of the English Association for outstanding scholarly work in the field of English Literature before 1590, and Honorable Mention for the Richard J. Finneran Award for 2013, awarded by the Society for Textual Scholarship.

How did I end up writing a book arguing that the most exciting announcement ever in Chaucer studies — in medieval literary studies, perhaps even in English studies as a whole — was, to be blunt, wrong?

When I first heard the news, ‘They found Chaucer’s own scribe!’, I was thrilled. This was Adelaide, South Australia. Winter 2004 there, summer up here. In the days before Facebook and Twitter, my first source of this amazing discovery was an undergrad who lurked on a medieval listserv. Soon enough in the New Chaucer Society’s newsletter I would learn about the ‘utterly persuasive disclosure of the identity of “Adam Scriveyn”‘, the addressee of an irritated seven-line poem called ‘Chaucer’s Words unto Adam His Own Scrivener’, ‘as Adam Pynkhurst’, whose entry into the Scriveners Company Common Paper in the 1390s looks rather similar to the most famous early copy of The Canterbury Tales, the ‘Ellesmere’ manuscript.

This was a bombshell. The teaching of Chaucer fundamentally changed. ‘Adam Scriveyn’ now offered us a window onto a historical reality: articles in the journals began referring to the ‘discovery’ of Chaucer’s scribe; Pynkhurst eventually received an entry in the Dictionary of National Biography; and both the scholar who made the discovery and Pynkhurst himself were fictionalized in various novels. As one critic wrote, the study of medieval English literature had experienced ‘a Copernican revolution’ since the announcement of his identity.

I was thus a bit surprised, upon settling into my office on the Strand after taking up a lectureship here at King’s in 2013, to come upon an essay from a few years earlier by KCL Emerita Professor Jane Roberts casting doubt on the claim. But this didn’t keep me from posting a celebratory Instagram photo of the book burnishing Pynkhurst’s credentials taking pride of place in my new office in the Strand Building.

The journey from there to Chaucer’s Scribes took a while to reveal its existence. In the wake of completing my previous book I was casting about for another project and found myself wondering about the scribal treatment of Chaucer’s metre. That led me elsewhere, to Thomas Hoccleve, who left behind some of his poetry in his own hand, enabling a proper study of the topic. Oh! I remembered: there was a newly-discovered holograph (copy written in the poet’s own hand) of Hoccleve’s most important work just around the corner, in the British Library. Hmm. It didn’t look like his hand. Its metre wasn’t his either.

Then came a few stages of writing, submitting, and dealing with readers’ reports that in effect said: look harder at the big picture. Read Scribes and the City (see Instagram screenshot above) way more closely. I had to do that a few times before I realized what was really going on. The story wasn’t just about Adam Pynkhurst but also about the Guildhall: Was it the cradle of English literature as that book and its attendant press releases claimed? More pressingly, it was about the ways in which scribes’ hands have been identified.

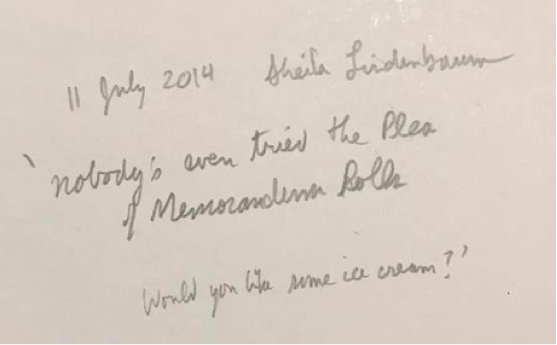

Well-timed conversations with experts in the field kept me on track. Sheila Lindenbaum invited me for lunch at her Marylebone flat and in the inside cover of my Scribes and the City I carefully recorded her words as she prepared pudding for us. This led to Chapter 4, presenting hundreds of new items in the hand of one of the most important scribes of Chaucer and Langland (‘the Huntington Hm 114 scribe’). Lisa Jefferson gave me a seminar on the production of the Goldsmiths’ Register of Deeds and Charters, in which that scribe played a major role. Tony Edwards and Jane Roberts shared their deep knowledge of medieval English manuscripts. I often went astray but advice from these and other colleagues in London and beyond brought me back.

Now that the book is out, what might I have done differently?

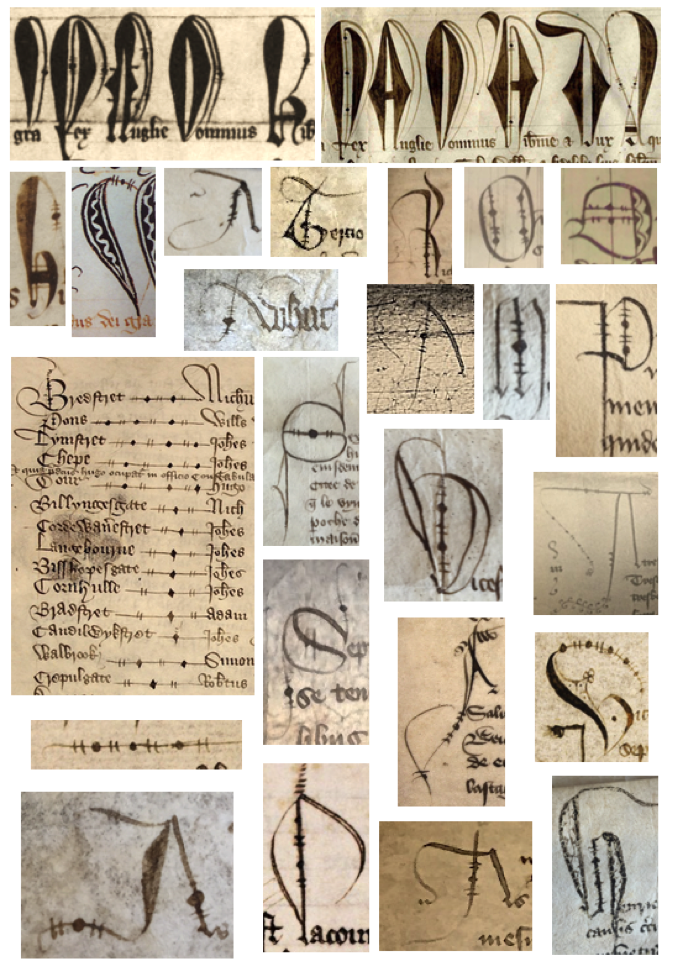

Now that the book is out, what might I have done differently? Not invite readers to open the online facsimile of the wrong manuscript at a crucial moment! (On p 39 top line, change ‘Tr’ to ‘W’.) Also, perhaps pushed a bit harder to include this collage:

This is more effective than my written list of representative appearances of the ‘double-slash, dot, double-slash’ motif from 1291-1415. Either way, the point is that the belief that this decorative feature was ‘Pynkhurst’s signature’, cited as the key piece of evidence that he was Chaucer’s scribe, is without foundation. Another little thing: a generous colleague has told me that one idea I discuss at length (if to deny its plausibility), that Hoccleve was Chaucer’s first editor, had been mooted decades earlier than I had realized, in a venue I should have checked. Such things happen and I’m sure there are other errors awaiting discovery, and that years from now I’ll wonder at why I wrote this phrase, sentence, chapter instead of that?

Otherwise I feel like Chaucer’s Scribes pretty much wrote itself, so the question is not so much what led me to write a book on the topic but rather what led to it being me who wrote that book? Big questions remain about how Adam Pynkhurst recast the field of Middle English manuscript studies in his own image. Perhaps one day someone else will write that book.

Featured images: courtesy of Lawrence Warner

You may also like to read:

‘Science Fiction was around in Medieval Times – Here’s what it looked like’

‘Founders of England? Tracing Anglo-Saxon myths in Kent’

‘The long read: Medieval women, modern readers’

If you have any comments on this interview please use the ‘Comments’ section of this blog post.

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.