by Rob Gallagher, postdoctoral researcher with Ego-Media

“I was photographed three times a week[,] for which I received a settled income…

Two famous dressmakers, one in London and one in Paris, dressed me for nothing, and a famous English designer called her models after me and made my clothes at a very nominal fee…

My picture advertised all sorts of wares, and face creams and soaps, and I gave advice in all the papers on how to keep healthy and beautiful and young. If I had followed the regime I laid down, I could never have finished in the twenty-four hours…”

So writes Constance Collier in her 1929 memoir Harlequinade, reflecting on her time as a ‘Gaiety girl’ on the 1890s Strand. On 8 February, I’ll be talking about Collier as part of an event at the London Transport Museum, themed around London love stories, representing the Centre for Life-Writing Research’s Strandlines project (an online archive of stories about ‘life on the Strand, past, present and creative’ – do contribute if you haven’t already…). I’ll be describing how Collier and her co-stars won the hearts of late Victorian Londoners with a series of racily contemporary ‘musical comedies’ combining cutting-edge fashions, romantic spins on everyday scenarios and saucy/sentimental songs. Pitched somewhere between ‘legitimate’ theatre and burlesque, musical comedies turned Gaiety impresario George Edwardes into a very rich man and many of his ‘girls’ into household names.

As Collier’s anecdote makes clear, the spectacle didn’t end when the curtain dropped; whether on or off the stage, Edwardes’ ‘girls’ were expected to embody a vision of modern womanhood altogether more fun (and less threatening to male privilege) than that of the suffragist or the ‘New Woman’. Using new media and collectible commodities to bring adoring fans closer to his ‘carefully selected, groomed and glorified’ performers (as Stephen Gundle puts it), Edwardes and his team helped to lay the groundwork for the Hollywood star system – not to mention the forms of self-branding, mediated intimacy and immaterial labour that have become all-pervasive in the smartphone era.

Gundle’s use of the term ‘groomed’ takes on a different resonance once you’ve read Harlequinade, which describes how Collier, while still a teenager, narrowly escaped being married off to a wealthy Gaiety patron before embarking on a disastrous affair with an older actor whose ‘magnetic’ hold on her is suddenly broken when he dismisses her as ‘only a Gaiety girl’. It’s fair to say she had the last laugh, leaving musical comedy behind to carve out a theatre and film career that would see her collaborating with Herbert Beerbohm Tree, D.W. Griffith, Eric von Stroheim, Noel Coward, Ivor Novello, John Barrymore, Alfred Hitchcock (that’s her as the aunt in Rope) and Katharine Hepburn (to whom she became dialogue coach, co-star and close personal friend).

Thought-provoking observations about gender, ethnicity and class…

The cameos make Harlequinade a treat for the cinephile, but it’s also a fascinating text in its own right. A good deal more literary than, say, Gaiety contemporary Ellaline Terriss’ memoir A Little Bit of String (named for her hit song, to which Terriss claims Edward VII knew all the words), it offers, amidst all the namedropping, some thought-provoking observations about gender, ethnicity and class.

Particularly striking – and often disturbing – are Collier’s thoughts on ‘race’, heredity and identity. After leaving the Gaiety (where, as Gundle puts it, ‘tanning was forbidden in order to preserve an aristocratic whiteness of complexion’) she took on a succession of roles that played on what she variously calls her ‘Latin’, ‘Mediterranean’ or ‘Arab’ heritage (her maternal grandmother was a Portuguese emigrée).

Whether as Cleopatra, Pallas Athene, Poppea or Ben Hur’s Iris, The Bohemian Girl’s ‘Gypsy queen’ or the native American Adulola, Collier specialised in providing Imperial Britons with palatable visions of otherness. In many of these roles we see her literally letting down the ‘lovely, dark, curly hair that my mother was so proud of’ – hair that, in an early episode from Harlequinade, she is made to plait by a severe schoolmistress who comes to stand for all the parochialism, ‘hypocrisy and prudery of the Victorian age’.

But in articulating her distaste for Victorian ‘morality’ Collier repeatedly falls back on the idea that her ancestry has made her romantic, vain and impetuous – reproducing, however wryly, equations of whiteness with rationality and mastery.

Similarly, in recounting how scandalized certain sections of British society were by the idea of aristocrats courting Gaiety stars like Rosie Boote (who became the Marchioness of Headfort), Collier rails against snobbery while enlisting the language of eugenics, declaring of these cross-class romances – ‘It was as if Nature were fortifying herself and using the blood and strength of these magnificent plebeians to build a finer race’.

Such moments shed light on the epistemic shifts theorised by scholars like Sylvia Wynter – King’s alumnus and subject of the recent Genres of the Human conference – who has described how, post-Darwin, oppositions between ‘rational’ enlightened Europeans and ‘irrational savages’ were recast in terms of evolutionarily selected or ‘dysselected’ populations, giving them a veneer of scientific legitimacy. Providing evidence of how individuals negotiated the implications of these shifts at the level of their own life stories and identities, Harlequinade suggests that new forms of ‘biologised’ racism gained a foothold in part because they seemed to promise a means of critiquing class prejudice, ‘hypocrisy and prudery’ – even for subjects who were themselves legible as non-white.

Constance Collier as an avatar of commodity capitalism, of modernity, of empire…

As someone who mostly works on contemporary digital culture, I’ve found it helpful to think of Collier as an avatar – an avatar of commodity capitalism, of modernity, of empire. I first encountered Harlequinade researching a 2016 project that brought together Strandlines’ work with that of Ego-Media, another Centre for Life-Writing Research project investigating ‘the impact of new media on forms and practices of self-presentation’.

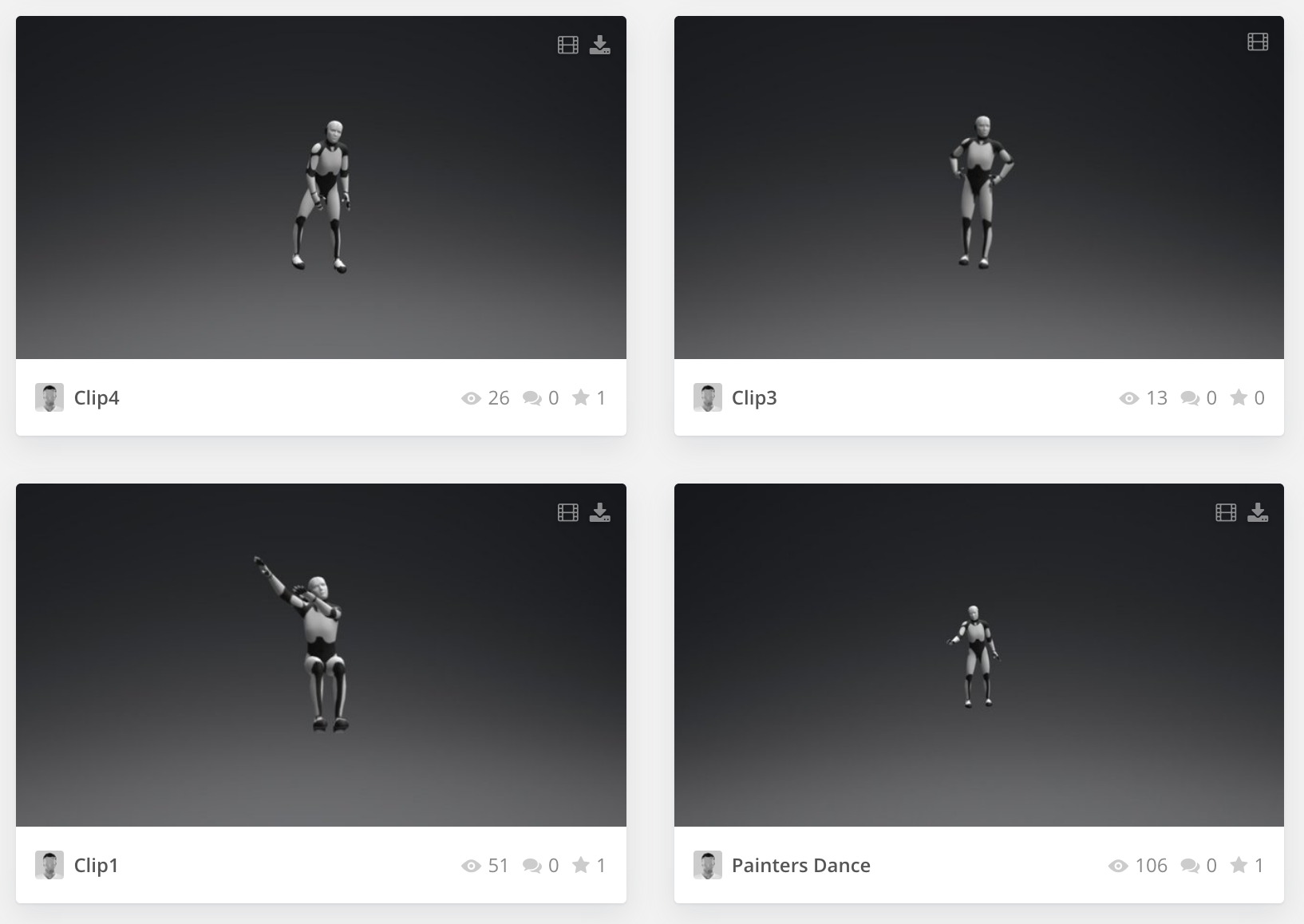

We commissioned Janina Lange, an artist with a track record of ‘reanimating’ early film actors as digital avatars, to create a pop-up ‘performance capture’ studio for the 2016 Arts and Humanities festival, where she recorded actor Meghan Treadway recreating snatches of Collier’s performances – including her stellar turn as Lady Dedlock in Maurice Elvey’s 1920 film of Bleak House. The resulting files were uploaded to Sketchfab, an archive of 3D models and animation files for use in games and CG movies.

With this gesture we wanted to draw attention to the changing terms on which technologies make life writable, highlighting Collier’s links to figures like the Instagram influencer, the Fortnite avatar performing dance moves stolen from black performers and the femme-presenting, superhumanly obsequious Amazon Alexa – all descendants, in their own ways, of the humble Gaiety girl.

Featured image, detail of a hand-coloured postcard of Constance Collier c.1895, C.W. Faulkner and Co.

Hear Rob discussing Constance Collier at the London Transport Museum Friday Late: London Stories, Friday 8 February 2019.

You may also like to read:

From broadcast to podcast: legacies of the BBC World Service, by Sejal Sutaria

Emily Brontë’s fierce, flawed women, by Clare Pettitt

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.