By Dr Alvin Eng Hui Lim, department alumnus and postdoctoral fellow at the National University of Singapore.

I’m on a British Airways flight from Changi airport, Singapore to Heathrow, London. The cabin crew, a mix of ethnicities, leaves me alone after the initial smiles and courtesies with the inflight entertainment, only punctuating my viewing experience a couple of times to serve me microwaved food – mostly chicken, or vaguely tasting like it.

I’m at Heathrow. A Chinese custom officer chides me in impeccable English for not completing the landing card before I join the queue. I do as told, and my voice struggles to complete a sentence when another custom officer addresses me and stamps my passport.

“What are you here for? What are you studying?”

“PhD. Theatre. At King’s College London.”

Maybe it is my face and how I sound. An inner joke seems to flash across his face as it changes. I am free to go.

I’m in the Barbican. I am watching a performance of The Master and Margarita directed by Simon McBurney. I’m enthralled and profoundly moved by it. It presents the possibility of adapting a fictional novel for the stage.

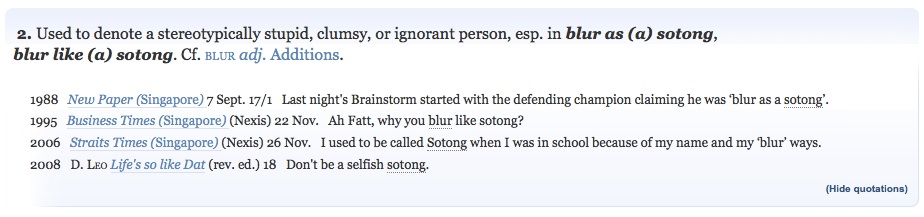

I think I look Chinese, a mix of Hokkien blood from two quite divided parts of Fujian, China. My pa’s father was from inner Fujian. My ma’s pa came from a region nearer to the sea. I don’t speak Hokkien as spoken in those parts. But I do speak the Oxford English Dictionary English:

“Wah, I am sorry for being blur like (a) sotong.”

That’s probably how I would apologise to the Chinese custom officer if I had the chance to again.

I’m in the Barbican again. I am here for an exhibition called Digital Revolution, where there are displays of abandoned software and archived video games. The earlier McBurney theatre production convinced me that I could begin to think of theatre as a medium of translation. It is also a medium of perception, where we begin to see people, texts and cultures differently depending on the languages we translate to and for. This exhibition however posits a future world where our apparatuses and modes of transmission are constantly diminishing in value, prone to retreating into the archive until we can no longer retrieve them.

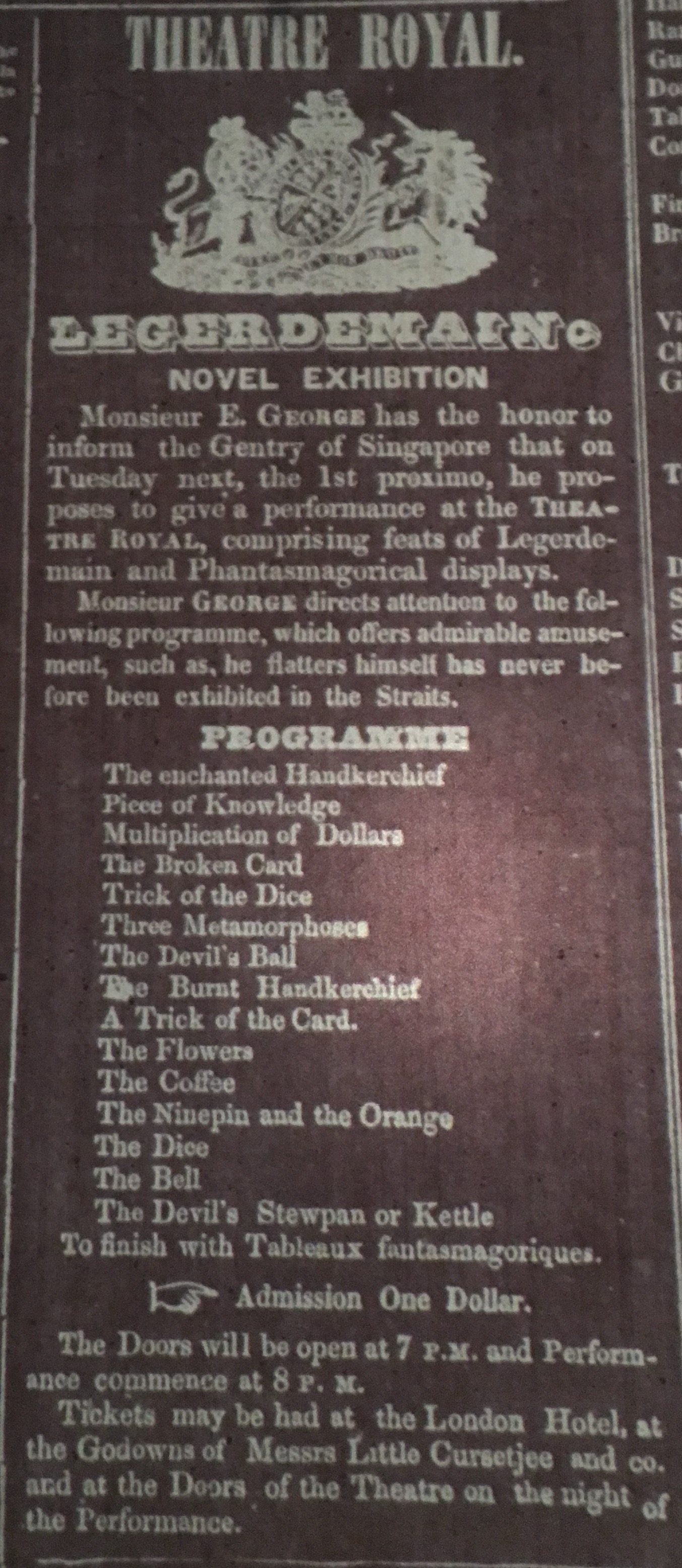

I’m in the National Library of Singapore. It’s three years since I was in the Barbican. I have started a new research project on island performances in the region and I want to research the theatres of the 19th century in Southeast Asia. Immediately, and inevitably, my first port of call is Singapore. A small column in a microfilm copy of the Straits Times on 28th November 1846 catches my attention:

In a December 1846 review, Monsieur George’s performances were described as “Legerdemain” and his displays “phantasmagorical.” His first appearance, however, “laboured under many disadvantages; his apparatuses not sufficiently prepared.”

It was a magic show, I assume. The Theatre Royal was a venue for all sorts of performances: amateur theatre performances, musicals and piano shows, and a magic show. I was assured that Monsieur George’s subsequent performance would be better, but I doubt I can be certain.

In another review, a year earlier in 1845, a group of amateurs were spared from a critical review:

“We are not disposed to criticize the performances, not only because it might lead us to make invidious comparisons but since they were Amateur productions we do not feel ourselves at liberty to indulge in observations lest they should be construed in a way wholly foreign to our intentions.”

There’s something phantasmagorical about my discovery of those English ‘Amateurs’ in Singapore performing in a newly built theatre called the “Theatre Royal”. It doesn’t exist now. But imagine a group of performers and musicians travelling great distances to an island to perform to their own kind – British colonials, or expatriates, or migrants, we could call them. Fast forward to a PhD candidate travelling on a plane to watch a show in London. This is a reflection on what it means to travel, the faces and phantasms we bring with us – labouring, like Monsieur George the magician, under their disadvantages and apparatuses. And sometimes the great effort and length we go to archive and remember them. Even as we forget them, I recognise that it is futile for my research to look for a definitive type of theatre of Singapore. Instead, theatres come and go, leaving behind traces of their biases. When we retrieve them, we imagine their origins anew.

This is a reflection on what it means to travel, the faces and phantasms we bring with us – labouring, like Monsieur George the magician, under their disadvantages and apparatuses.

Tigers also visited Singapore. In the same newspaper issue, “a report which obtained currency of the visitation of tigers (more specifically a tigress and her cub) in the neighbourhood of Singapore.” Curiously, their visitation took them to “Dr Montgomery’s plantation,” and a Chinese compound.

I am reminded of Anthony Burgess’ Malayan Trilogy, and the image of ang mohs – Westerners – drinking Singaporean Tiger brand beer.

“It was genuinely the magic hour, the only one of the day. Both men, in whites and wicker chairs on the veranda, facing the bougainvillea and the papaya tree, felt themselves to begin to enter a novel about the East. It would soon be time for gin and bitters. A soft-footed servant would bring the silver tray, and then blue would begin to soak everything, the frogs would croak and the coppersmith bird make noise like a plumber. Oriental night. As I sit here now, with the London fog swirling about my diggings, the gas fire popping and my landlady preparing the evening rissoles, those incredible nights come back to me, in all their mystery and perfume…”

So writes Burgess.

I’m in London again, in 2016. Oriental night in a North Indian restaurant. I sit here now, with ang mohs, and with the London lights projecting those incredible nights I had a few years ago in all their mystery and with lukewarm tea… London is my East. Seems like it is since the OED decided to claim Singlish – Singaporean English – as part of their dictionary: sotong, ang moh and others. Perhaps we reciprocally share a history, and despite all the disadvantages of those apparatuses of colonial production, the magic hour, or as we say here “Tiger Time,” is upon us to write anew the figurative visitations of tigers and magicians with failed and successful attempts to light up our neighbourhoods.

Dr Alvin Eng Hui Lim is a postdoctoral researcher in the Theatre Studies department at the National University of Singapore. He completed his PhD as part of the joint doctoral programme between King’s and NUS in 2015.

The image above shows the tiger at Singapore’s theme park of Chinese folklore and mythology, Haw Par Villa, which was built in 1937 and named after the famous Aw brothers, inventors of Tiger Balm.

You may also like to read Postcards from Mindanao

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and not those of the English Department, nor King’s College London.