By Sylvia Solakidi, student on the MA in Theatre and Performance

On November 30th 2015, performance projects developed by the students of Performance Lab – an MA module run in the English Department during the autumn term – were presented in the Anatomy Museum, Strand Campus. The module was taught by Dr Harriet Curtis as a workshop comprising performance-based activities, student-led practice and seminar discussions on, among other topics, aspects of intimacy in the work of influential performance artists that have attracted vivid scholarship during the last decade.

Eight students with backgrounds in acting, dance, visual arts, art history, drama, literature, philosophy or the political sciences, performed intimacy through quasi-autobiographical seven minute works-in-progress. This format turned space, time and spectatorship into works-in-progress too, so that performers and audience became explorers in and of the Anatomy Museum. In this performance venue, haunted by its previous use (evident in its name), an ebb and flow of relations between “here” and “there”, “now” and “then”, stillness and movement of bodies, objects, light and sound was generated. Such currents moved the explorers from one work to another, into an intensity nuanced by different degrees of engagement with the intimacy of autobiographical memory and experience.

Performances were autobiographical in different degrees depending on the intimate elements that were chosen, edited and embedded in them by the performance enacted by memory. The resulting performance of self-identity also became a work-in-progress by regarding oneself in self-referential ways (Maiko Okumura, Adėle Reeves), through the enactment of a persona (Emilie Labourey, Alys Williams) or by projecting oneself on staged rituals inspired by the everyday (Lissie Carlile, Minnie Lai, Estelle Papadimitriou, Sam Shepherd).

The fluid state of ‘stages’ and ‘auditoriums’ invited different kinds of exploration, as the question ‘where is the stage?’ was transformed into ‘when is the stage?’

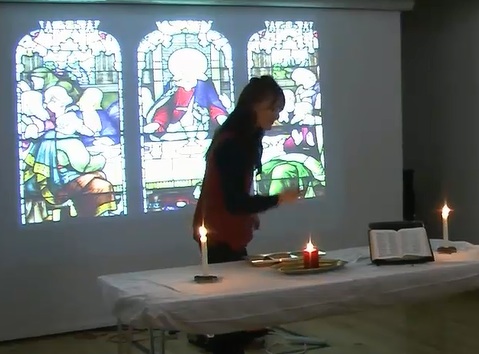

Autobiography also invaded the space literally in the form of chairs and tables, creating a ‘shock’ analogous to that produced by furniture in the theatre of realism, as described by Bert O. States in his book Great Reckonings in Little Rooms. In the Anatomy Museum, chairs and tables were not just furniture, but the objects whose movement and stillness assisted the bodies of the explorers in framing the enactment of autobiography. The arrangement of the chairs for the audience continuously changed from corridor-like patterns to lines reminiscent of traditional theatre venues. Alternatively, chairs were pushed against the walls so that the audience could move freely and congregate in circles around works. This fluid state of “stages” and “auditoriums” invited different kinds of exploration, as the question “where is the stage?” was transformed into “when is the stage?” When an area became the “stage,” appropriate light and a table were introduced to it (in the case of Lissie Carlile the “table” was a piece of cloth on the floor, while Maiko Okumura had no table at all). The “stage” was claimed by the performers to be the private space of the enactment of autobiography. As a result, the Anatomy Museum acquired a hybrid character of private and public space, whose areas slid into one another and couldn’t be mapped in advance. Thanks to currents of intimacy and distance, the mutability of the performance space was made evident. In fact, the first performance initiated a movement with periods of tension and relaxation, as explorers moving in the space paused for each piece before moving again in a ritualistic way reminiscent of the Seven Stations of the Cross, as Alan Read described the experience afterwards. The exploration of the unmapped territory across an itinerary in the process of becoming turned the eight pieces into a more unified group work-in-progress, bearing the features of what David Wiles defines as a ‘processional narrative’ in his book A Short History of Western Performance Space. Such a process was experienced in the various parts of the narrative in Alys Williams’ piece And tonight thank God it’s them instead of you. Alys, dressed as a priest, transformed the Anatomy Museum into a church and invited the audience to explore the various stages (welcome and readings, offering and hymn, blessing, donation) of a subversive service that bitterly and ironically criticized the distanced and oversimplified attitude of the worshipful West towards the problems of the Third World.

The aforementioned currents channeled the dynamic between audience and presentational spaces, as well as the potential for exchange among explorers. Participants were invited into a relation by using the inevitable distance between performers and audience as the space of what art historian Kristine Stiles defines as ‘commissure,’ where a ‘metonymic interconnection’ between the bodies of performers and audience can take place. Performers made an invitation for such a relation but it was up to audience to choose it or not, as was the title of Minnie Lai’s piece Awareness – Choose it or not. Minnie’s stage was a table lit by a spotlight, on which she was preparing smoothies. After she had finished, she left the stage and let the audience decide whether they would explore a relationship with her or would avoid tasting what she had prepared. The lights came up and the audience had the choice to inhabit the stage or keep its distance from it by remaining seated. In his piece Connected but alone Sam Shepherd demonstrated the difficulties of not only persuading the audience to participate, but of even finding it in the darkness of social media. Performing along a dark corridor whose edges were lit by a computer screen and a candle and whose sides were the chairs of the audience, Sam quested for fellow-explorers. While trying to make enough space for the encounter to happen, he challenged audience’s gaze, as they were free to choose whether they would look at him or at the screen, depending on which image seemed more “real” to them.

I have already mentioned that the advent of chairs and tables has caused a shock to the theatre of realism. The kind of realism at stake in the Anatomy Museum, though, was far from the idea of art imitating nature. As the intimacy of autobiography invaded the performance space, a realism that did not mimic everyday life (or its furniture), challenged what is considered to be “real” in a space. In her piece Table for two, criticizing Marine Le Pen’s unwillingness to provide schools with pork-free meals, Emilie Labourey enacted a persona enjoying “real” pork and wine in lunch with an invisible female Muslim companion. While Emilie’s character was recalling childhood memories, the table for two became a table for one, since the Muslim companion didn’t eat. It also became a table for many since the Anatomy Museum was transformed into a French restaurant, with the audience adopting the role of restaurant goers overlooking Emilie’s table. It finally became a table for nothing, since Emilie’s character consumed everything, as if she didn’t want to leave any “real”, material traces, as if nothing had ever happened.

The Anatomy Museum is “real” in yet another way. Until 1997 when the last dissection of corpses took place at the Anatomy Theatre, a performance of death was taking place there, violating intimacy and demonstrating parts of human bodies in jars filled with formaldehyde. This “something else” that the place was before clashed with the reality of the white cube-like performance venue, turning it into what Marvin Carlson (in his eponymous book) described as the “haunted stage,” so that the movement of the living bodies also invaded a realm of dead bodies, haunting the performance space. In her piece Exercise in futility, Estelle Papadimitriou demonstrated to the audience the irreversibility of dissection. Sat in front of a low table full of votive symbols, she brought an onion out of a cup. She set a timer to seven minutes and performed this duration by cutting the onion in ever smaller pieces and crying. She also had near her a basket with potatoes from which we could hear through earphones the voice of Dylan Thomas reading a poem about death. After the timer had rung, Estelle collected the pieces of the onion in the cup and left. While explorers were crawling in order to take a better look at the table and be able to hear Thomas, the irreversibility of time and memory was performed through the mundane task of cutting an onion. The clash of realities in which memory has the leading role was at the core of the piece Prosaic rights by Adėle Reeves, who demonstrated on a table seven non-museum objects, which she linked to a stage of Buddhist enlightenment and to a story from her everyday reality. Not only the objects but also the stories were demonstrated, for the audience to explore the relationship between visual and textual narratives.

These bodies explored a space in which the body had once been treated as a thing, or in the Cartesian metaphor, as a clock that runs out of time.

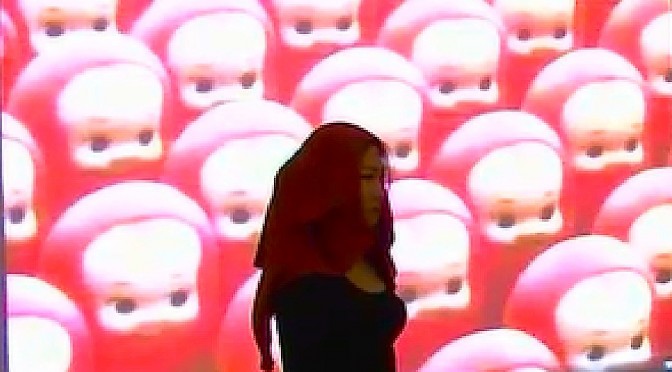

These bodies explored a space in which the body had once been treated as a thing, or rather, to refer to the Cartesian metaphor, as a clock that runs out of time – a notion which turns anatomy museums into spaces where no intimacy is allowed. By exploring this particular space, autobiographical bodies performed two returns by re-performing both their own history and the history of the Anatomy Museum. Thus, they became messengers bringing messages both from “there” and “then” to the “here” and “now”. In the piece My body knows, Maiko Okumura danced while on the screen behind her were projected scenes of discipline from Japanese schools, dance schools and work places, treating the body as a mechanical clock always attuned to rules. But Maiko is a dancer, her body resisted the dead discipline to which it had been submitted and tried to find its own steps, by returning to the time of repression projected on screen and confronting it.

This double return of performers invited a double encounter from the audience too, which was invited not only to perceive aspects of autobiography, overcome its otherness and achieve intersubjectivity, but also to come to terms with the alterity embedded in the space, the radical otherness of death. In the performance Hush now, my darling, Lissie Carlile confronted motherhood as otherness. While a crying baby and the voice of the mother trying to calm it down could be heard from a recording, Lissie performed representations of breastfeeding and birth on screen and on the floor, respectively. In order to give the impression that milk was pouring from her breast she had placed a bottle of milk on her skin by adhesive tape and, like a child playing with plasticine, she made a baby out of minced meat. The on screen violence of the adhesive tape on her skin, the large knife which she used to open the parcel of meat and the white sheet in which the minced meat baby was covered, turned her stage into a crime scene and motherhood into a slaughter. Our ritualistic exploration of living intimacies turned unexpectedly into a ritual of violence and death. The proximity of intimate relations subsided and revealed the Janus nature of the encounters among explorers, the particular nature of currents of intimacy generated in a space haunted by the memory of death.

*

(There is no smell in Anatomy Museums. But I cannot help recalling the smell of formaldehyde, so familiar to me from my work in a hospital laboratory, even when I enter the Anatomy Museum at King’s. The smell is still in my nostrils.)

You may also like to read Reimagining the Witness in the Eternal City: Who is the Last of the Cencis?