Yasmin [EDIT Lab PhD student] outlines our latest publication on anxiety symptoms in the family. Anxiety in parents is associated with anxiety in offspring, but it’s not yet clear how this happens. We conducted the first study to use a ‘genetically sensitive’ research design to examine the effects of mother, father and child anxiety symptoms on each other over time.

Background

Researchers have shown that anxiety disorders tend to run in families – with the children of anxious parents being at increased risk for anxiety compared to the children of non-anxious parents 1, 2. But how does this happen?

Lots of research has been published on the idea that anxious parents might behave in ways that influence the development of anxiety in their children. Most of this research has been focussed on mothers, for a variety of reasons 3. However, we also know that anxiety is influenced by genetic factors 4, so it is crucial to account for the fact that parents and children share the same genes. Because of this, children might inherit genes associated with the development of anxiety from their parents, which makes it difficult to be sure whether the association between parent and child anxiety is due to shared genes and/or because they live together. Very few researchers examining anxiety symptoms in families have accounted for familial genetic relatedness.

A third possibility, which was proposed in theory more than fifty years ago 5, is that anxious children might behave in ways that influence their parents’ anxiety levels. Even though this makes sense theoretically (i.e. we know that parent-child interactions are transactional, with both parents and children able to influence each other) – until now there have been no published studies using a genetically informative research design to examine possible child-to-parent anxiety effects.

Current study

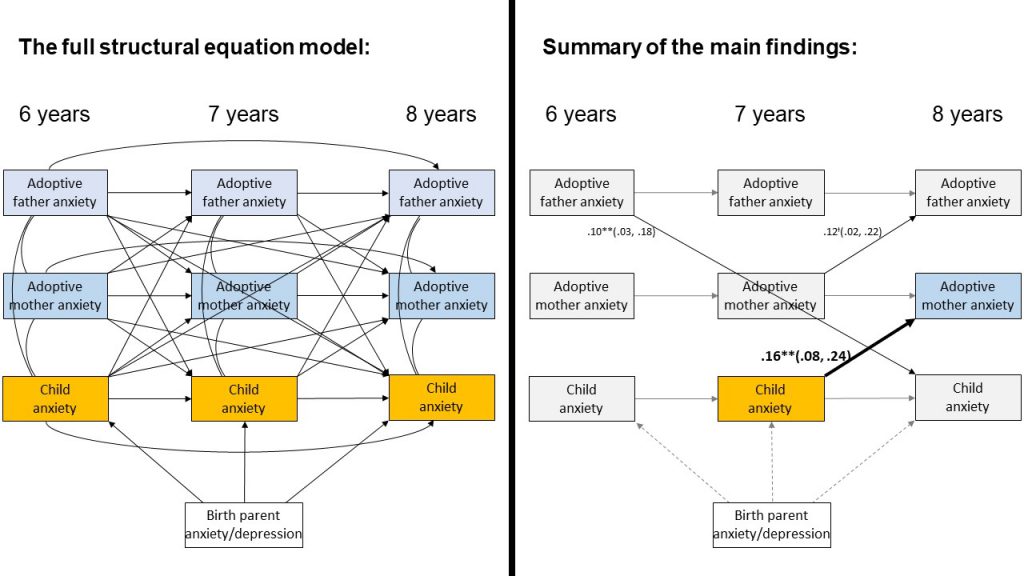

We examined transactional (parent-to-child and child-to-parent) associations between mother, father and child anxiety symptoms across a three-year period during middle childhood (child ages 6 – 8 years), using structural equation modelling.

We used quantitative measures of anxiety for 305 adopted children, their adoptive mothers and fathers, and their biological mothers and fathers 6. Adoptive families provide a natural experiment for the study of genes and environments in families. When children are adopted to non-relatives at birth (as in our study), they inherit their environment from their adoptive parents and their genes from their biological parents. Therefore, we could be sure that any observed associations between adoptive parents and children were due to environmental influences, not shared genes. Conversely, any associations between biological parents and adopted children would primarily be due to genetics.

Child anxiety at age 7 predicted mothers’ anxiety a year later. This was found in all models. Father’s anxiety at age 6 predicted child anxiety at age 8, but only when fathers’ reports of child symptoms were included in the models. Standardised parameter estimates: ** p<.001, Ɨ p=.05 (95% CI), dashed lines = non-significant.

What we found

We show that adopted child anxiety symptoms at age 7 were associated with adoptive mothers’ anxiety symptoms a year later. This finding remained consistent in all our tests of the data. It provides novel evidence for an environmental effect of child anxiety symptoms on mothers’ symptoms. We didn’t find the same for fathers, which suggests that having an anxious child may be more anxiety-provoking for mothers compared to fathers.

We found no evidence for an effect of adoptive mothers’ anxiety symptoms on adopted child anxiety. This was striking, given that most previous research has been focussed on understanding mother-to-child transmission only. We did find that adoptive fathers’ anxiety symptoms could predict future child symptoms, but only when fathers’ reports of child symptoms were included in the model (which may be indicative of bias in the fathers’ reports – such that anxious fathers were more likely to report having anxious children).

Finally, we found that adopted child anxiety symptoms were not associated with anxiety and depression among biological parents. Therefore, we found no evidence for a genetic association between parent and child symptoms – although this may reflect measurement or statistical power issues.

Take home message

In future research we must consider the effects of child symptoms on caregivers, taking a family-wide perspective in relation to parent-child anxiety associations. We must strive to include fathers in assessments and ensure that we continue to employ genetically sensitive research designs – to identify meaningful environmental effects on anxiety within the family, which may be malleable to intervention and prevention strategies.

Acknowledgments

With special thanks to the birth and adoptive parents from The Early Growth and Development Study; the adoption agencies who helped with the recruitment of study participants; and the research team who managed data collection and scaling.

Citation

References

- Lawrence, P.J., Murayama, K., & Creswell, C. (2018). Anxiety and depressive disorders in offspring of parents with anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 58, 46–60.

- Micco, J.A., Henin, A., Mick, E., Kim, S., Hopkins, C.A., Biederman, J., . . . & Hirshfeld-Becker, D.R. (2009). Anxiety and depressive disorders in offspring at high risk for anxiety: A meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23, 1158– 1164.

- Phares, V. (1992). Where’s poppa – the relative lack of attention to the role of fathers in child and adolescent pychopathology. American Psychologist, 47, 656-664.

- Boomsma, D.I., Van Beijsterveldt, C.E.M., & Hudziak, J.J. (2005). Genetic and environmental influences on Anxious/Depression during childhood: A study from the Netherlands Twin Register. Genes, Brain and Behavior, 4, 466–481.

- Bell, R.Q. (1968). A reinterpretation of direction of effects in studies of socialization. Psychological Review, 75, 81–95.

- Leve, L.D., Neiderhiser, J.M., Shaw, D.S., Ganiban, J., Natsuaki, M.N., & Reiss, D. (2013). The Early Growth and Development Study: A prospective adoption study from birth through middle childhood. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 16, 412–423.