As a developmental psychologist I’m pretty aware of the signs and symptoms of depression and anxiety. However, our school recently ran an evening lecture on supporting well-being in our children and It really made me think about things in a different way – and in particular, to consider how anxiety and depression can masquerade as all sorts of other emotions. This week is Child Mental Health week, so it seems a good moment to reflect on how we can support the well-being of children around us.

Depression and anxiety disorders are diagnosed on the basis of sets of core symptoms including sadness and loss of pleasure (for depression) and fear and worry (for anxiety). As discussed in a previous blog, anxiety disorders come in all shapes and sizes, and to further confuse things, we all experience some of these symptoms at least some of the time. The point at which clinicians decide that anxiety or depression need to be dealt with, is when they interfere with daily life. This, however, can be a particularly hard call to make for those caring for young people.

The development of these disorders in young people is not just about impact on daily life; it may also be about reaching a tipping point in terms of emotional stability. This was one of the opening points made in the lecture I mentioned earlier. It was given by Dick Moore, who is one of the Charlie Waller Memorial Trust trainers. The Charlie Waller Memorial Trust was set up in 1998, in memory Charlie Waller, a young man who took his own life due to depression. Sadly this tale is all too common, and suicide is the leading cause of death of young people (aged 20-34) in this country.

Of note, whilst women are much more likely to be diagnosed with anxiety and depression, suicide rates show quite the opposite pattern. Approximately 4 times as many young men take their own lives as young women in any one year. It is the Trust’s mission to help create a world where people understand and talk openly about depression, where young people know how to maintain wellbeing, and where the most appropriate treatment is available to everyone who needs it. They have recently made a video (which you can watch at the end of this post or by clicking this link) explaining what they do, which includes providing financial support to research relevant to the development and prevention of depression – and they have trainers, such as Dick Moore, who speak at schools.

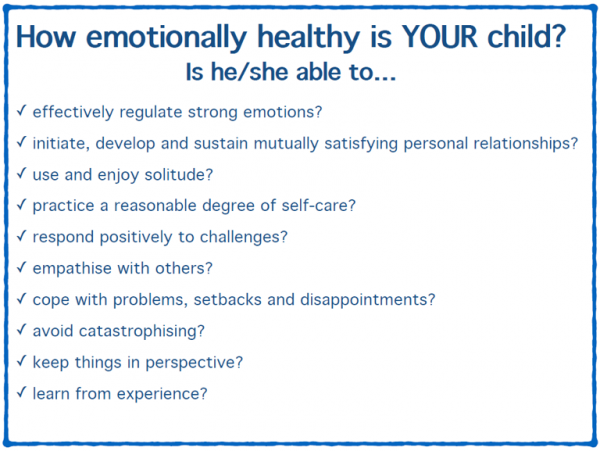

Dick Moore is particularly well qualified for this role. He has been a teacher and headmaster for much of his career, and has suffered the heart-breaking loss of a young man to suicide. This experience led him to change direction and to spend his life teaching people how to recognise emotional instability in young people. His talk was really excellent. Grounded in the latest research findings, it was presented in such a way that it made sense to everyone. He opened his talk by suggesting we each hold a child we knew in our head (the audience also contained teachers), and then count how many of the questions in the box below we would say ‘YES’ to, when thinking of that child.

I found this a really fascinating experience, because the majority of these items do not relate to the classic symptoms and signs of anxiety or depression. As a mother of 3 sons, I found myself totting up scores for each of them – and the results surprised me. Of my three sons, it was the one that I least often think might be worried or sad that had by far the poorest score. The emotion he expresses most often is anger, and this speaks to the heart of what was so interesting about this list.

At the core of these questions is the concept of emotional lability, or the ability to regulate and manage emotions. Clinicians and researchers have, for a couple of decades now, looked at the concept of emotional regulation and its association with depression, but as parents and teachers it is all too easy to label a child or teenager that manages their emotions badly as naughty rather than sad or worried. This can lead to a negative spiral with parents responding in an unsupportive way to such emotional displays, and the situation thus worsening. But the reverse also applies, and supportive parenting (e.g. problem-focussed solutions, such as suggesting where to look for a lost item) is associated with higher emotional regulation abilities in offspring. Of course, unpicking the links between parental behaviours and child outcomes is not straightforward, and requires the use of some innovative methods (as summarised in another post on this blog).

“Individuals have a genetic liability to respond in an emotional way to stress, but that the specific emotion they display, and the time at which it occurs, will relate to the qualities and timing of the stressor”

Another reason I found this list so interesting, was that we know from behavioural genetic research that genetic influences on different aspects of mental health problems overlap a lot. For example, there is very high genetic overlap between the different types of anxiety and depression in children, adolescents and young adults. Furthermore, genetic influences on these problems tend to be quite stable, and to be the primary cause of stability in emotional difficulties over time. Even more interesting is that these studies also show that the contribution of the environment tends to be far more specific – impacting on just one type of emotion at just one point in time. I have always interpreted this as support for the idea that individuals have a genetic liability to respond in an emotional way to stress, but that the specific emotion they display, and the time at which it occurs, will relate to the qualities and timing of the stressor.

Interestingly, this whole idea goes beyond just the links between anxiety and depression (which we know co-occur together far more often than would be expected by chance). There is also evidence that genetic factors are an important factor in terms of overlap between behavioural problems (such as defiance or aggression) and emotional problems (such as worry or sadness). This shared genetic influence may be mediated by broader trait assessing “negative affect”. As such, these behavioural problems, are themselves sometimes expressions of other very powerful emotions (e.g. anger, frustration) which could simply be masks for underlying fear or sadness.

So, what do I conclude from this? Well, it is really important that more people understand that it isn’t only children that appear sad or worried who are at risk of depression – but also those who struggle to control any emotions, including anger. Fundamentally, children often need our support the most when their behaviour makes us feel least willing to give it.

My 10 yr old son has suffered a lot of bereavement his dad age 3 our 2 dogs age 7 and his grandfather most recently last week. Is there somewhere I should be accessing for help for him. He does actually seem to be behaving appropriately occasional sadness, forgetting about it for a bit, feeling guilty about that etc thanks in advance – Sarah

I’m sorry to hear of your difficulties. As you say, some sadness and guilt are to be expected, but if you are at all worried I would suggest speaking with his teacher first to see how he is getting along at school. If you do have concerns your GP should be able to provide support as well. Thanks for getting in touch. Thalia

[…] Thalia’s recent blog post highlighted the devastating fact that suicide is now the leading cause of death of young people (ages 20-34) in England and Wales. Moreover, the issue of the gender difference in suicide rates was raised. Thalia’s post noted that “whilst women are much more likely to be diagnosed with anxiety and depression, suicide rates show quite the opposite pattern. Approximately 4 times as many young men take their own lives as young women in any one year.” […]