by Max Saunders, Professor of English at King’s College London

Max Saunders shares the story behind the exhibition Alfred Cohen: An American Artist in Europe which was due to open at The Arcade at Bush House in March 2020. The exhibition had to close to early due to COVID-19, but is now available to view online.

When my step-father, the painter Alfred Cohen died in 2001, my mother, Diana Cohen, and I decided that rather than having a funeral or memorial service, which he’d have hated, we’d celebrate his life with a memorial exhibition in his studio instead. As I started tracking down his earlier work for the show I became fascinated with how different it had been and how many different but equally engaging styles and techniques he had evolved. He was a much more versatile and mercurial artist than I’d realised.

As one collector put us in touch with another, and we remembered more names, it turned into a large exhibition – over 100 pictures. And things have snowballed ever since. One collector ran the London Jewish Cultural Centre, and suggested transferring the exhibition to London. Which we did, discovering more works as people saw the adverts and wrote in sending photos.

The show got some amazing reviews. The Ham and High described his work as ‘a revelation’. Howard Jacobson especially admired the haunting figures of Punches and Columbines from the Commedia dell’Arte and wrote a long piece in the Independent saying that the work should really be in the Tate.

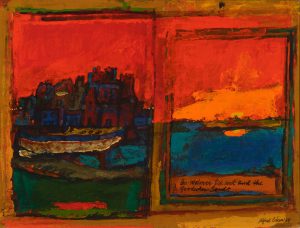

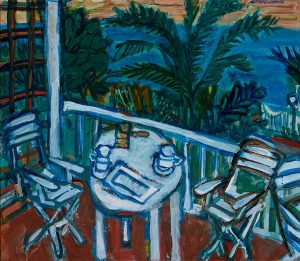

Alfred had been treated like a celebrity when he came to London in 1960 and showed in prestigious West End galleries through the 60s and 70s. Film stars and producers bought his shimmering pictures of the Thames, or his haunting, energetic theatrical figures. The exhibitions got some superb reviews then too – saying his work had ‘a visionary quality’, and was ‘immediately striking and lastingly memorable’. One particularly thought-provoking comment came from the Tatler, of all places: ‘Look . . . at almost any few square inches of a Cohen canvas and you have a little gem of abstract painting’. The Daily Telegraph called him ‘one of the best draughtsmen at work to-day’.

But then pop art and conceptualism completely changed the art world, and Cohen’s type of figurative painting suddenly went out of fashion. That didn’t deter him, and he kept working till the morning he died. He had a following in East Anglia. He had lived in Norfolk for over 20 years – in the same School House where Henry Moore had lived while an art student – and Diana has run a successful modern art gallery there since the 1980s, selling Alfred’s work alongside her stable of talented local artists and exhibitions of international stars like Hockney, David Jones, and even Moore himself. But Alfred’s last solo London exhibition in his lifetime was in 1986; and it was over forty years since his work was seen regularly there. Artists were increasingly expected to explain their own work and promote themselves. Alfred would cringe as they did it and wouldn’t do it for himself.

Though a lot of the collectors I met, or met again after 40 years, still enjoyed his work, in some cases the pictures had been neglected; relegated to attics, or damaged in damp basements. The business of tracing and borrowing the earlier pictures for the memorial exhibitions was partly rescue work. The Alfred Cohen Art Foundation was set up soon after, to collect such endangered work, and restore it when necessary. It became a registered charity, and a number of collectors very generously donated works to it. In its first 18 years it has acquired over 100 works, many of which it has subsequently placed in major public collections.

There was one striking change once people had seen the range of Cohen’s work again: Museums and collections started to get interested. In the last 5 years the Jerwood Gallery, the British Council, Pallant House, and the Southampton City Art Gallery have all acquired work. The Norman Foster-designed Sainsbury Centre at the University of East Anglia has nine works; the Arts Council has just acquired three.

Another development has been the take-up by art historians and critics. I had originally thought for Alfred’s centenary in 2020 to publish a slim book illustrating his pictures, for which I’d write a brief biographical introduction. I went to consult American art expert David Peters Corbett at the Courtauld Institute of Art about it and he suggested holding a study day there devoted to Cohen. That was unexpected, as was the number of brilliant young curators, art critics, art historians and artists who contributed talks. That led to a second workshop, this time at one of the other major art history venues in the country, the Paul Mellon Centre for the Study of British Art. That raised an interesting question. Was Cohen’s art American or British? Hmmm. . . Both and neither, probably. His greatest influences were European: the Impressionists, Expressionism, the Ecole de Paris, Picasso, Dufy and other Post-Impressionists. But as Paul Greenhalgh, Director of the Sainsbury Centre, has said about Cohen: ‘When you look at him you don’t especially think he’s an American or French or British painter; he’s dealing with an international modern language’.

What matters is that both fields wanted to be involved. And that a new generation of experts has something to say about his work. At the Mellon Centre workshop Greenhalgh spoke of how today’s art students had a real hunger for paint – the physicality and materiality of it, and of attention to painterly technique. I’d heard it said that there was now a return of interest in figurative painting of the later 20th century; but this made it sound like the 2020 centenary was really the right time to show Cohen’s work again. In the words of art historian and TV presenter Jacky Klein: ‘It really feels now that he is an urgently important artist. . . the art world is suddenly interested, the public are much more interested, in these forgotten masters of the second half of the 20th century, who are such a critical part of the story of modern art.’

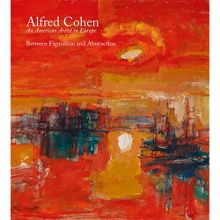

So the Cohen Foundation started planning an exhibition. It seemed especially important that his work should be seen again in London for the centenary. The book had now turned into something more like a catalogue to accompany it (though it illustrates far more works than we could exhibit). And the workshops had developed essays for the book, which includes contributions by Greenhalgh, Peters Corbett, Klein, journalist David Herman, and several others, including three former King’s English PhD graduates who also work in visual culture: John Berger’s biographer Tom Overton, curator and critic Hope Wolf (now at the University of Sussex), and writer and filmmaker Deborah Baum (now at the University of Southampton). I provided the biographical introductions to each section, based on recordings I’d made with Alfred over the last five years of his life. I’ve written lives of writers before and written about life writing. But writing family history, and especially finding the right tone to write the life of a parent, were certainly new challenges.

The exhibition started snowballing too. When I was directing the Arts & Humanities Festivals at King’s I worked closely with the Culture team there, so I proposed a Cohen exhibition to them. I also met with Sarah MacDougall, the Head of Exhibitions and Collections at the Ben Uri Gallery and Museum. Alfred’s first London exhibition had been at Ben Uri in 1958 and their Collection includes two of his works. Sarah was interested too, and agreed to co-curate the show with me and co-edit the catalogue. Ben Uri even offered to co-publish the book with the Cohen Foundation and get it distributed through the Antique Collectors Club Art Books website which they use for their exhibition catalogues. This was a marvellous opportunity for me. Though I’ve taught and written on literature and the visual arts, I’d not worked with art historians so closely, and had what I now realise was a very sketchy understanding of how art books are made.

The Ben Uri had held its 50th anniversary exhibition also at King’s College London and a staggering 30,000 people had seen that show. Staggering partly because the gallery space it was in, the Inigo Rooms in the East Wing of Somerset House, was well tucked out of sight in a basement. King’s has since installed a state of the art gallery space in the ground floor Arcade of Bush House, freely open to the public and visible from the street. The Culture Team accepted the exhibition proposal and later said they felt it should go in the Arcade. Suddenly it began to sound as if Cohen’s work would get some serious exposure in a central London venue for the first time in half a century.

The Sainsbury Centre agreed to be a partner in the centenary project. In 2016 they had organized an exhibition of Cohen’s work as part of the King’s Lynn Festival. Now they offered to put on a Cohen display at the Centre. The Cohen Foundation, another partner, decided it would stage a second exhibition after the one in London. One of its Trustees spoke to the modern curator at the Norwich Castle Museum, whose Gallery houses the magnificent collection of Norwich School nineteenth-century landscapes. The Castle Museum offered to host yet another show, of Cohen’s landscapes, in their new Colman Experimental Space next to the Norwich School gallery. One exhibition had now become four. . .

And then a film. . .or two. . . The Cohen Foundation had taken on a fundraiser to help raise the money for all this activity, and he had successfully funded a cinema in Norwich, and works with Coda Films. When I asked for advice about getting a video made about the exhibitions, this too started snowballing. The producer went to the Foundation, looked at Cohen’s work at the School House, and interviewed Diana. And he decided he thought there was material for a full-length documentary there too, to be pitched to a commercial broadcaster like Sky Arts.

Somehow we had got from a plan for a book of the paintings and a not very clearly-formulated plan for an exhibition, to two day-conferences, four exhibitions, a large book with 20 contributors, a video, even a film. Oh, and a longer-term fundraising strategy and plan to open an Alfred Cohen Museum, also for the centenary. Two years ago I didn’t even have a publisher for the slimmer book project, let alone arrangements for any of the rest of the programme. I wouldn’t have believed it could all happen, and so quickly.

Over the Christmas break the final editing of the book was done and it was sent off to the designer. Then the last work on designing the exhibition began. We measured all the walls, planning the hanging of each on Powerpoint slides, to make sure the pictures looked right together. With the help of designer Susen Vural we worked on the texts to go on the walls; the captions for each picture; the eight-page gallery guide; the design on the front window visible from the Strand. We sent out invitations for the private view.

The week before the show opened the excitement levels soared. The books arrived on Tuesday, a day early. The designer Izzie Thomas had been an exacting taskmaster about the illustrations, and I’d had to get a number of the works re-photographed. But he’d been right, and the results looked stunning. On Wednesday the technicians, Martin Abrams & Reuben Thurnhill, arrived to do the installation. Sarah and I worked with them over two days, making last-minute adjustments to the hang, organising the smaller pictures, sketchbooks and archival material in a large vitrine. It was wonderful to see the exhibition materialise. Martin and Reuben kept up their infectious good humour all through, even when we asked them to move pictures they’d just hung.

Even then, on Thursday 12th March, it was impossible to think of the word ‘infectious’ without thinking of COVID-19. It had become clear from the news over the preceding weeks that the virus was spreading, and that it would probably affect attendance. The show was to have a run of 10 weeks, and I was worrying that the end of it might be curtailed. We had decided to finish the installation on the 12th so as not to have it happening on Friday 13th, just in case. But the bad luck arrived a day early too. We were just hanging the last two pictures on Thursday afternoon, when the staff from the Culture Team came over, looking ashen-faced. They had just been told that the College was suspending meetings of more than fifty people, so our private view would have to be cancelled. Even then there was no talk of closing the exhibition itself. But that possibility had suddenly loomed much larger and closer.

I spoke to Coda Films. They wanted to include footage from the exhibition in the longer documentary, and agreed to come down from Norwich on Tuesday to capture it while they could, do a few more interviews, and perhaps some ‘vox pops’ from any unsuspecting visitors. The show officially opened on Monday, and people started coming in. But that evening the Prime Minister advised people only to make essential journeys. Luckily Coda Films felt shooting in the gallery was essential to their project and were still prepared to go ahead. Diana, in her 90th year, had been planning to come down for the private view. She came anyway, determined to see the show that we’d been planning for so long. Coda were able to interview her walking around the gallery, and also interview some of the book’s contributors. A handful of friends and relations joined us. A much more private view than we’d imagined. . . That afternoon the College decided to start locking everything down and it became clear the exhibition too would have to close by 7.00 p.m. – exactly the time the speeches were scheduled to have been starting at the private view. A private view always feels like the official opening of an exhibition, even though it had been possible for people to see this one over a couple of days. From that point of view, we opened and closed at the same moment, making it possibly the shortest exhibition in history.

But luckily we had the film footage and also images from a still photographer who had also been working that day. We decided the only thing to do was to put the exhibition online, hoping that at least people would be able to see it in that form and to watch the film. Sarah arranged for an excellent web designer to construct the online exhibition.

It’s not how we’d envisioned the centenary playing out. And it’s still impossible to know whether the events later in the year in Norfolk will be able to go ahead, or can be rescheduled. But in the meantime, the show at King’s has already garnered some coverage in leading publications such as The Art Newspaper and Time Out.

The King’s Culture Team is continuing to promote the show in its online form on social media. And I’m posting a picture a day from it on Instagram and Facebook, to invite comments from the public. So if any of the images here appeal, please add your thoughts about the pictures as they are posted: it’d be great to hear your responses and interpretations!

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.

You may also like to read: