From Thursday 16th May to Sunday 19th May The Store X Gallery at 180 The Strand will be hosting FOUND: A Harold Feinstein Exhibition , the UK’s first ever exhibition of the legendary, 20th century American photographer Harold Feinstein. The exhibition is accompanied by screenings at the Curzon DocHouse of Andy Dunn’s film Last Stop Coney Island: The Life and Photography of Harold Feinstein.

Dr. Michael Collins, Senior Lecturer in Twentieth-Century American Literature and Culture in The School of English, chatted with the curator Carrie Scott about Feinstein’s work and legacy, American photography at mid-century, and the place of optimism in art.

Michael Collins [MC]: Do you want to introduce yourself? How did you come to be interested in U.S. mid-century photography?

Carrie Scott [CS]: I am a curator and Art Historian based in London, and while I am English by birth, I grew up in America. My love for photography, in general, began when I was pretty young. My godfather gave me my first camera (a Nikon from memory), and my granddad had a Rolliflex (I think) that he didn’t use so gave to me to play with it. I didn’t ever shoot anything with it, but I liked to pretend.

The first photography exhibition I can remember going to was [Richard] Avedon’s Evidence at the Whitney [ed. Richard Avedon’s Portraits and collections Evidence, The Sixties and In the American West are landmark works of American photography and social documentary of the late twentieth-century USA]. I think my Dad took me, but I don’t know for sure. I looked up the date of that show recently. I would have been 15. It was a big survey show and some of the images were printed larger than life. One room had this long, monumental shot of women and men both dressed and undressed; their crotches were almost at eye level. I remember being shocked by its size, its bravery, its urgency (which is something that comes up a lot for me in Feinstein’s work). I am sure I had seen other photography exhibitions before that (and am sure someone in my family will pipe up when they read this and tell me just how many I saw) but Avedon’s left an almost indelible mark on me.

Thinking back on this, it’s crazy to me that Avedon, like Feinstein, was asked to be in [Edward] Steichen’s Family of Man. It’s impossible not to wonder how things would have been different if Feinstein had agreed to being part of that show.

MC: Great to have been able to have seen the Avedon show and that it inspired you so much, especially as a budding photographer. I can also imagine what it would have been like at 15! With your Dad! Pretty embarrassing. What you describe about the impact is a thing with Feinstein, I think, too. There is something in the nature of his work that doesn’t keep you remotely at a distance or tell you that it is the work of “master” (although it is) so you shouldn’t try and emulate it. You want to be part of his world, or to document you own. It’s very inspirational like that.

I should add that Edward Steichen’s Family of Man is probably the most famous and important photographic exhibition of the era. Art historians are all pretty puzzled why Feinstein didn’t want to be included. He was asked. I think we can probably trace a little of his lesser fame relative to his talent to that decision. Bizarre, and frustrating.

I am excited that you are bringing Harold Feinstein’s work to the UK. We are pretty unaware of it here, I think. Tell us a little about him and where he came from – personally and socially.

CS: It’s crazy, but you’re not alone. Most people don’t know Feinstein’s work. I didn’t until the Director, Andy Dunn – who shot Last Stop Coney Island – the feature length documentary on Feinstein’s work and life (which premiers in the UK on May 15th) brought his work to my attention. That was about three or four years ago. Andy had just started shooting his documentary and asked if I’d take a look at the work and speak to Judith Thompson, Feinstein’s incredible widow about the estate. I think I saw three pictures on Andy’s phone and was hooked. And with a little digging, I couldn’t believe I didn’t know his work.

Feinstein’s life paralleled the greatest era in modern photography and the New York Times obituary called him “one of the most accomplished recorders of the American experience.” How had I missed this? By way of a little background, Feinstein was born in Coney Island, in 1931 to Jewish immigrant parents. He began photographing Coney and the streets of Brooklyn at the age of 15 with a Rolleiflex he borrowed from a neighbor. At 16 he dropped out of school and devoted himself to photography. In 1948, at the age of 17, he became the youngest member of the historic Photo League and by the age of 19, Edward Steichen, director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, had purchased his work for the museum’s permanent collection.

He had so much early success with inclusion in group shows at The Whitney Museum and MOMA, and later solo shows at the George Eastman House (1957) and Helen Gee’s Limelight gallery (1958). Throughout the 50s, Feinstein was a part of the New York art scene and was one of the first inhabitants of New York’s legendary “Jazz Loft.” During that time he designed covers for Blue Note and Signal records along with Andy Warhol and Reid Miles. In 1957, he was asked to join Jean Paul Sartre and Samuel Beckett in launching the first issue of the avant-garde literary magazine Evergreen Review, which featured eight pages of his photographs.

At around 26 he began teaching from his studio, and his workshops became notorious and acclaimed. In 1960 he was invited to be one of the first teaching fellows at the Annenberg School of Communications in Philadelphia and after that continued to teach from his studio and at numerous institutions for the rest of his life. Among his students were Mary Ellen Mark, Ken Heyman, Louis Draper, Wendy Watriss and Bob Shamis.

MC: It really is exciting. There are moments in life and research when you discover figures like this. Huge in their time, but so badly neglected now. There’s no feeling like it in the world. I know our American Studies and Literature students would be thrilled to hear about the relationship with the 50s art scene, the “Jazz Loft”, Sartre, Beckett etc. I’m fascinated to learn about the Blue Note records covers. They are so central to anything we think of a “mid-century modern” American style. Feinstein was right at the centre of that.

What do you see in his work that you think has been missing from the discourse about photography in the period?

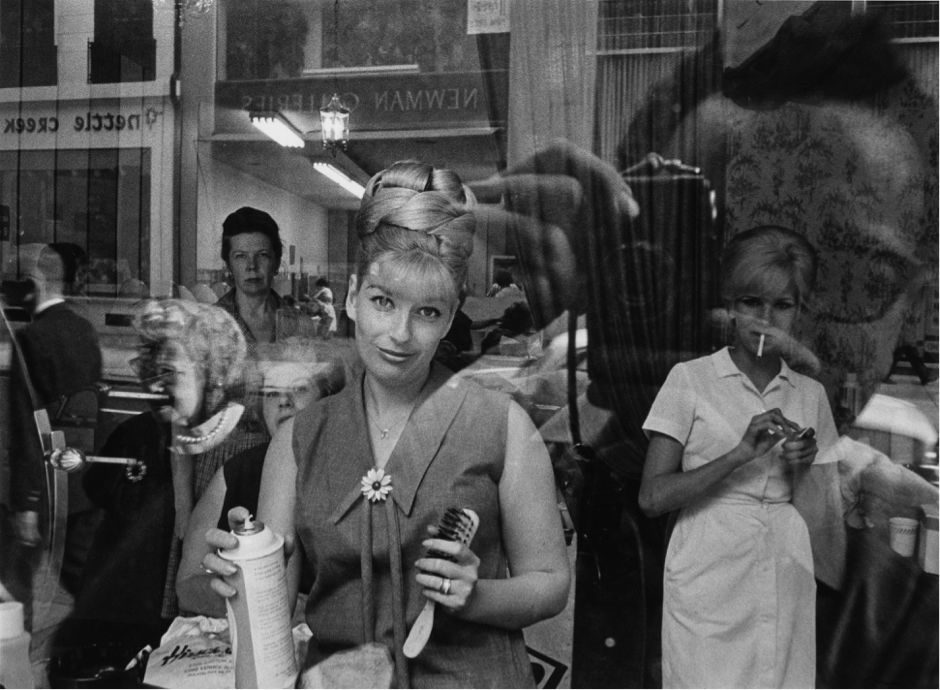

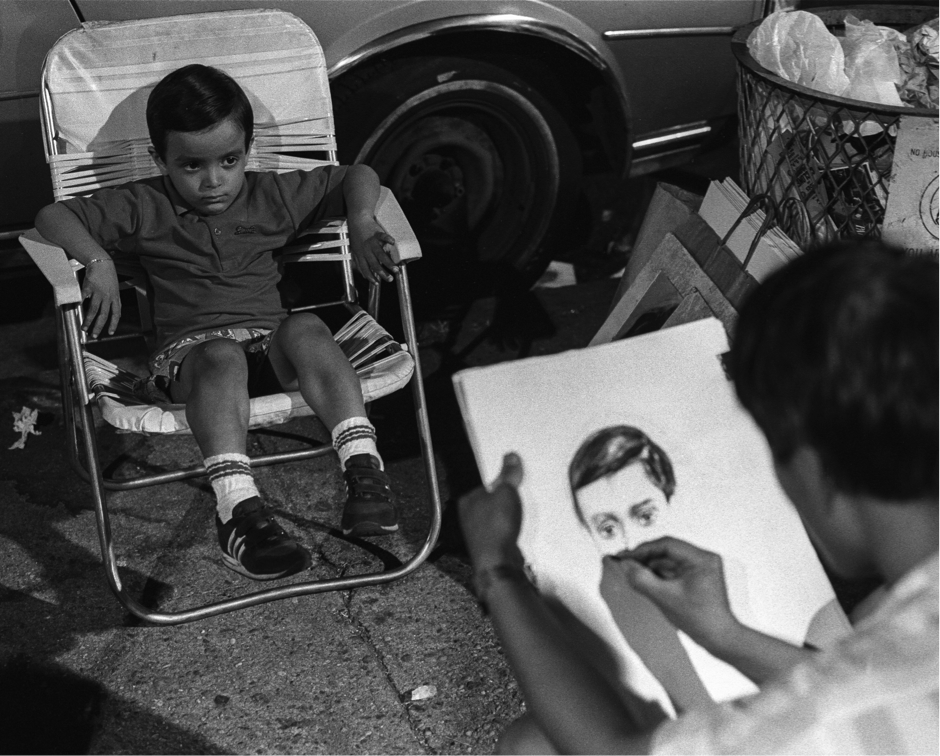

CS: I think there’s a freedom and, dare I say, a joy to Feinstein’s work that isn’t so palpable in other work from the era. And actually an intimacy that’s almost urgent. Each composition builds from the middle, as if Feinstein saw something that caught his eye and then the frame filled around the focal point. Of course, compassion sits at the core of each composition. This was a photographer who, above all, celebrated humanity with his subjects. His desire to connect with the world around him and share the beauty he saw is evident in every single frame and composition. For the press release I wrote something along the lines of “People stare into his lens, eyes sparkling. No one holds back. Life is vivid. And, full.” And intimate. In Feinstein’s images we see the world through his own intimate love for the world. He wasn’t a documentary photographer, but an artist, telling his story, telling us about his love for life.

MC: It’s so important. A big question in art and literary theory at the moment too; how we capture the experiential pleasure of art; what is at stake in our tendency as critics to buy into a suspicious, negative, questioning stance; and the canons of work we build to represent an era as reflecting that too. I’d like to see Feinstein shown alongside Robert Frank’s The Americans, works by Gordon Parks, Diane Arbus, and Roy DeCarava for example. It would be an interesting exercise in expressing joy and/or despair and what we bring to mid-century photography.

A follow-up question or two. Who do you think are his main influences and how does he break from them? Who do see as an obvious counterpoint to him and his work?

CS: Small format photography was really only just beginning when Feinstein started out. So, I don’t know that he was influenced by that many folk around him. That said, you can easily look at Diane Arbus’ work, or Henri Cartier-Bresson’s and see some parallels. But Feinstein’s was not a photographer who would stand back and observe, unnoticed by his subjects, in fact, in nearly every image, Feinstein’s proximity to his subject is remarkable. It’s this physical closeness, which I think is an extension of his empathic connection to his subjects that sets his work apart from other Street Photographers of the same period.

MC: Do you think our understanding of the U.S. has changed at all in recent years? What does Feinstein’s work reveal that we might often forget about post-War America?

CS: Oh dear, what a big question. I bet your students could answer this far better than I can. I don’t know what they tell us, really, from a historical perspective that we don’t already know; America is not what it used to be, but in that post-war moment there was prosperity and freedom and calm. Personally, I do look at them and wonder if people, on the whole, were happier then and more engaged in the world around them. God that makes me sound (and feel) old.

MC: Yeah, I reckon they could answer that better than either of us actually, too!

If you had to sum up Feinstein’s aesthetic what would you say about it?

CS: Joyful precision.

MC: Do you have a favourite work in the exhibition? Why?

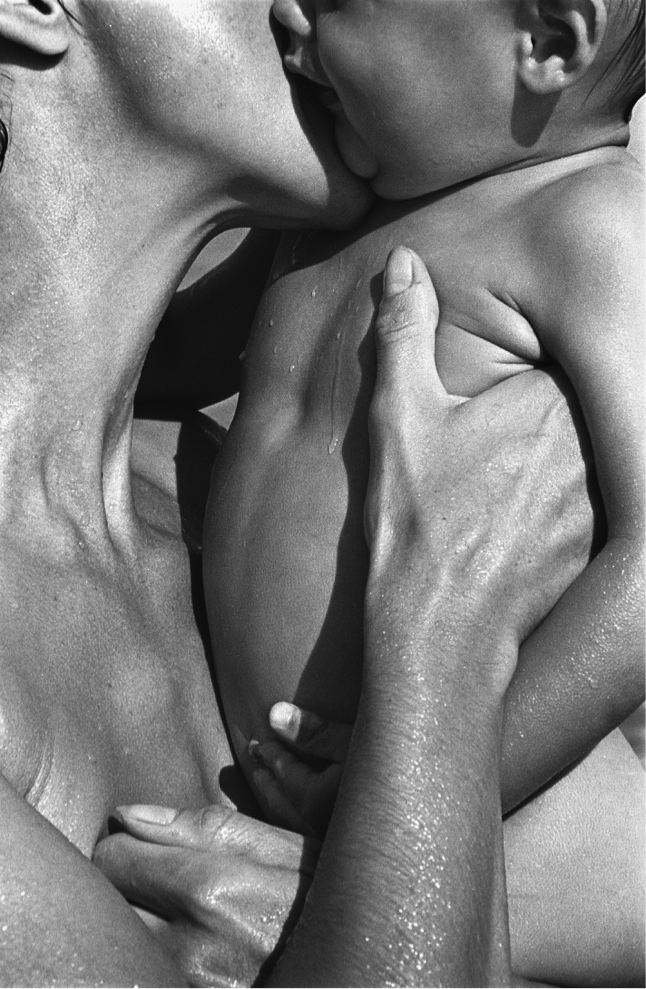

CS: I do. In 2017 I organized a talk, and had a small pop up of Feinstein’s work for Photo London. My second son was 3 months old at the time. When the crate came with the pieces I wanted to show, there was this super close up image of a mother holding her child that I’d only seen in jpegs (while pregnant and had kind of dismissed my love for it precisely because I was pregnant). The composition is so totally Feinstein – all up close and person. The mother in Feinstein’s composition is squeezing the nude body of her child up against her face. The light is incredible. The quality of the print is so appealing. And the image captures a desire I never had until I became a mum – this need to almost eat your kids. I wanted to buy it before anyone else did, but told myself it was hormones. Months later I still wanted to buy it. So I did. It still speaks to me, as a mother, in a way that no image ever has.

MC: Something that is always a source of concern with mid-century modern style is that it can lose its edge in our art world – especially to pieces that perform a more overt “politics” around identity, race, civil rights etc. How do you avoid imagery that might be associated with “Americana” seeming corny?

CS: That’s the thing with this work. It might be corny. It might be optimistic. It is totally beautiful. That’s indisputable. And I for one, I am sick and tired of those things being bad. In my opinion, there’s an edge to happiness. It doesn’t come easily. Most people have to work at it. I don’t know that Feinstein did. I think he saw it everywhere and embraced it with both arms. These images aren’t banal. They aren’t sentimental. They aren’t clichéd. They are totally fresh.

MC: I love that too. You say it so well. Optimism is so hard. It is work for most of us. Yet it is so important. For Feinstein it just sort of shines through.

Finally, what plans do you have for the exhibition after its time at Store X?

CS: We do indeed have plans to take the show – or a version of it – on to other locations, none of which am I at liberty to divulge at the moment. Andy and I have so enjoyed the integrated aspect of next week – with the Film premier (there are still tickets available to the Sunday screening at DocHouse Curzon) and the exhibition – that we are targeting other cities that might be able to host both at the same time. Ultimately, I would like to see the ultimate Harold Feinstein book published, and his place in this moment in history secured.

MC: Carrie, thank you so much for taking the time to answer my questions. I wish you the very best of luck with the exhibition, film, the tour, and, finger’s crossed, the retrospective book.

All Images Courtesy of Carrie Scott and the Harold Feinstein Trust

FOUND: A HAROLD FEINSTEIN EXHIBITION

presented in partnership with Carrie Scott

Store X London, 180 The Strand

(Free Entry)

Thursday 16 May: 12pm -9pm

Friday 17 May: 12pm – 9pm

Saturday 18 May: 12pm – 7:30pm

Sunday 19 May: 12pm – 6:30pm

Thereafter the exhibition will be open until May 26th by appointment only.

Email info@carrie-scott.com to set a viewing time.

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.

If you have any comments on this interview, or would like to ask Mike or Carrie any further questions, please use the ‘Comments’ section of this blog post.

You may also like to read:

- ‘They were heady days’: Reflections on cruising, theory, and Queer@Kings

- Ideologies of integration and exclusion: An interview with Dr Christine Okoth

- Painting in circles and loving in triangles: The Bloomsbury’s Group queer ways of seeing