by Clare Pettitt, Professor of Nineteenth Century Literature and Culture, Department of English

“The first action of the battle of Manchester is over”, wrote Major Dyneley of the 15th Hussars, “& has, I am happy to say ended in the complete discomfiture of the Enemy.” At 4 pm on August 16, 1819, Dyneley was already back in the Hulme Barracks with his regiment. The “Enemy” was the 60,000 to 80,000 people, most of them textile workers, who had assembled that morning in St Peter’s Field on the outskirts of Manchester city centre, to hold a peaceful demonstration to protest against the Corn Laws, and to call for parliamentary reform. The Enemy was the people. And discomfited they had surely been.

Henry Hunt, the orator who had addressed the meeting briefly before being arrested and beaten up, said that the Manchester Yeomanry, volunteers who made the first incursion into the crowd, before the Hussars, had “charged amongst the people, sabring right and left, in all directions. Sparing neither age,sex, nor rank”. It all happened very quickly. Ten minutes after the first charge, William Joliffe remembered that “the ground was quite covered with hats, shoes, musical instruments and other things”. Another eyewitness recounted that, “[s]everal mounds of human beings still remained where they had fallen, crushed down and smothered.

Some of these still groaning, others with staring eyes, were gasping for breath, and others would never breathe more”. At least twelve died, and the sabres, an edged weapon designed to slice and cut, caused horrific injuries for hundreds more, while others were trampled or crushed to death. One man had “his Nose cut down to his face”; another, William March, had a “sabre cut on the back of his head, bone in his leg splintered and crushed on the body by being trampled on. He states that he had three children working in Birley’s factory, who, when he learnt of his being hurt at the meeting, discharged them”. The full number of casualties and deaths will never be known, as many had to hide wounds from employers to keep their jobs.

Even The Times was shocked. “Was that at Manchester an ‘unlawful assembly’? Was the notice of it unlawful? We believe not.” The people had thought themselves safe, they had dressed up in their Sunday best, put flowers in their buttonholes and taken their children with them to the meeting. They had expected that if they behaved reasonably and respectably, the State would respect their rights. They were horribly, terribly wrong.

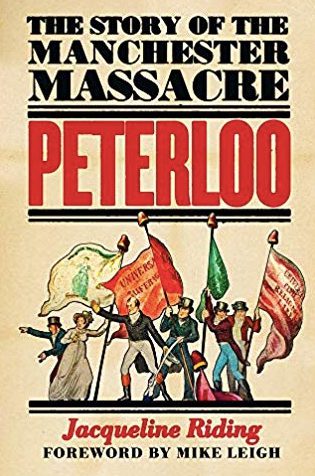

Mike Leigh, whose beautiful, fierce and intelligent film ‘Peterloo’ comes out this week, understands that historical drama is always also contemporary drama: “poverty, inequality, suppression of press freedom, indiscriminate surveillance and attacks on legitimate protest by brutal regimes are all on the rise”, he reminds us in his brief foreword to Jacqueline Riding’s clear-minded and readable book, ‘Peterloo: The Story of the Manchester Massacre’, published to accompany his film.

‘Peterloo’ is long (154 minutes), demanding and utterly compelling. There are echoes of Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece ‘Barry Lyndon’ (1975) in the eerie use of music which is often diegetic, and the cutting between cramped dark interiors and pellucid, damply green scenes on the moors above Manchester. Leigh’s film also resembles Kubrick’s in the intelligence with which it inhabits its period. As a historical-political film, ‘Peterloo’ never falls into the Manichaean simplicities that flattened Sarah Gavron’s ‘Suffragette’ (2015). Contemporarily relevant it may be, but Manchester in the early nineteenth century remains an alien, complicated and unrecognisable place, and Leigh refuses to sentimentalise its working-class inhabitants.

Peterloo is about shared and collective experience. This is not Dickens, or even Gaskell, and there are no shots of abjection and filth, no romantic plot and no central character.

Instead, the film uncompromisingly offers a great deal of serious talk. It celebrates an autodidact working-class oratorical tradition. This is generally deftly done, and there are only one or two moments when the political exposition feels staged, as when a family sit around their kitchen having a usefully factual chat about “the bread tax” (the Corn Laws of 1815 which kept the price of bread high).

Many of Leigh’s characters are based on real historical people, such as Samuel Bamford (played by Neil Bell). Bamford started his education at Middleton Sunday School, where he remembered that scholars came from far around: “[b]ig collier-lads and their sisters from Siddal Moor were regular in their attendance . . . with their substantial dinners tied in clean napkins”. Bamford, a weaver, radical and poet, read Bunyan and spoke fondly of “my old Homeric Pope, and my divine Milton”.

The poetry and rhetoric of these working-class leaders hold deep memories of the republican hopes of the English Civil War. Eighteen-year-old John Bagguley (Nico Mirallegro) told a meeting that, “I am a Reformer, a Republican, and a Leveller”: the Civil War Levellers were committed to popular sovereignty, extended suffrage, equality before the law and religious tolerance. Such speeches made the Government very nervous. Spies were employed to report back to the Home Office on the “contagion” of radical reading: “They have taken four or five rooms for the purpose of reading Cobbett in”.

But Leigh does not idealise his workers, and their political meetings are realistic in that some speakers are long- winded and tedious, and some are electrifying. In ‘The Peterloo Massacre’ (1989), republished to mark the bicentenary next year, Robert Reid remarks on “the inability of the working class to produce from its own ranks leaders who were effective as well as charismatic”, which, he says, “was a weakness which would persist well beyond the beginning of the twentieth century”.

In fact, as Jacqueline Riding points out, the only reason that Hunt, a well-heeled campaigner for reform, took to the hustings as the star speaker at St Peter’s Field that day was that all the local working-class leaders had already been rounded up, beaten and imprisoned. It was not “weakness” that prevented the working-class leaders from leading, but the State.

“The eyes of all England, nay, of all Europe, are fixed upon you”, Henry Hunt wrote in an address to the people on the eve of the meeting at St Peter’s Field. Known as the “Wiltshire Peacock”, Hunt was always happy to have all eyes fixed upon him; his charm and overweening vanity are brilliantly rendered by Rory Kinnear.

But Hunt was right that this was a thoroughly international event. The cry of the American Revolution, “No Taxation without Representation”, was stitched on banners alongside the French “Liberty and Fraternity”. Fraternity was explicitly cross-Channel and transatlantic; in Leigh’s film, the worker- orators appeal directly to the example of their “French brethren”.

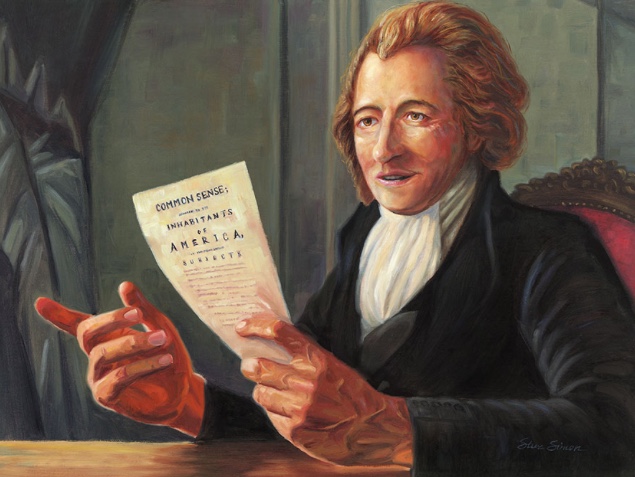

Manchester was internationally networked through trade, and the literate industrial poor were kept well informed by the Manchester Observer, and by radical publishers such as Richard Carlile (Joseph Kloska), who published the works of the Anglo-American radical Thomas Paine. Leigh transposes much of the film’s dialogue directly from records and archives. At one point, we hear Paine’s famous injunction in “Common Sense” (1776) to Americans, “we have it in our power to begin the world over again”.

The illiterate and semi-literate could follow events through ballads and broadsides of the kind collected with helpful exposition by Alison Morgan in ‘Ballads and Songs of Peterloo’, and by looking at prints and cartoons. Riding reprints contemporary satirical cartoons between her chapters which remind us of the rich radical visual culture of this period and its importance to the growth of democratic thinking. The Home Office was particularly panicked by any appearance of the French revolutionary red Cap of Liberty, as “this symbol gives a character to the meeting which cannot be mistaken”, and was nothing less than “the insignia of treason”.

Magistrates counted 18 flags and five caps of liberty being waved at St Peter’s Field. It is extraordinary that, despite the triumphant nationalism released by Wellington’s victory over Napoleon at Waterloo only four years earlier, the British industrial workers continued to identify themselves with Continental radicalism and transnational revolutionary thinking, and to see their best chance in international solidarity. For them, the Regency represented the British ancien régime, and Tim McInnerny’s Prince Regent in Leigh’s film is a mordant reminder of the contempt in which the working people were held.

From Cold Bath Fields prison in 1817, Bamford had written to his wife, “send my trousers my other hat, white handkerchief &c &c as I wish to be decent”.

Leigh’s film emphasises the decency and dignity of the people, not only by their words, but also in long shots of their daily lives.

A servant goes upstairs to announce a visitor and the camera lingers on him as he climbs the steps. We watch Maxine Peake’s character, the working-class matriarch Nellie, as she makes a hand-raised pie, we see pages of the Manchester Observer being peeled wet off a hand press; single eggs are carefully sold; and, more chillingly, an overworked cutler sharpens sabre blades. We see Bamford preparing his Middleton section for the big meeting to “exhibit a spectacle such as had never before been witnessed in England”, drilling them in disciplined marching with a band. This was not unfamiliar: at the Lancashire Wakes and Rush-Cart festivals, the people would parade in their best clothes, the carts decorated with laurel and flowers, and the horses decked in “horse-gold” (tinsel).

Middleton’s workers approached St Peter’s Field “in the greatest hilarity and good humour”, Bamford remembered, and “all were decently, though humbly attired; and I notice not even one, who did not exhibit a white Sundays’ shirt, a neck-cloth, and other apparel in the same clean, though homely, condition”. The attention to textiles in the film is exact and appropriate, for the workers in “Cottonopolis” were experts. Bamford’s Middleton section were proud of their banners, one Prussian blue and another of green silk, and “on a tall staff was a red velvet Cap of Liberty, tastefully braided with the word LIBERTAS”. Thomas Redford, “who carried the green banner, held it aloft until the staff was cut in his hand, and his shoulder was divided by the sabre of one of the Manchester yeomanry”.

The women sewed the shirts and braided the liberty caps, but that was far from all they did. The Manchester Female Reform Union was led by Mrs Mary Fildes (Dorothy Duffy), and the meetings attended by women across the country caused particular alarm to the authorities.

Alice Kitchen of the Blackburn Female Reform Society testified to their growing poverty: “we can speak with unassuming confidence, that our houses which once bore ample testimony of our industry and cleanliness . . . are now alas! robbed of all their ornaments”.

The rhetoric was carefully domestic although many women were also working long hours in the factories. It was usual for politically active and vocal women to be savagely lampooned in the press as shameless whores. On the way to St Peter’s Field, the marching women were abused by other women along the route. Mary Fildes composedly led her section of women through the fray; they were all dressed in white and marched behind Hunt’s carriage. Their presence was taken as a safeguard against violence; “the presence of the ladies always chastens the company”, according to John Smith (Gary Cargill), editor of the Liverpool Mercury.

But it did not work on this occasion. “The women seemed to be the special object of the rage of these soldiers”, wrote James Wroe (Harry Hepple) in the Manchester Observer. The soldiers targeted the women’s breasts with their sabres. John Tyas (Leo Bill) in The Times described “a woman on the ground, insensible . . . with two large gouts of blood on her left breast”. More than a quarter of all known victims were female, although women comprised only about 12 per cent of the crowd. Mike Leigh could have added vicious misogyny and a fury against women who have the temerity to speak publicly to his list of the issues still with us today.

The film is agonisingly effective in showing the bewilderment of people as it dawns on them that they are in mortal danger and nobody is going to help them. What effect did Peterloo have? Leigh’s film ends with the burial of one of its young victims and ventures no conclusions. The immediate effect was that the hastily passed “Six Acts” ushered in a period of even more swingeing censorship and repression. Repeated attempts to win legal redress for the victims all failed, scuppered by the Government.

But word got out. Carlile left Manchester at 3 am on the morning of August 17 on the first mail coach to London to publish his graphic account. The Manchester Observer published a series of detailed reports, and John Tyas’s report in The Times, which appeared on August 19 after he had been released from prison, caused a sensation in Britain and abroad. Archibald Prentice felt at the time that this press coverage had created “a marked and favourable change in the current of public opinion”. The working-class radical movement grew into Chartism, the internationalism of 1819 surfaced again across Europe in 1848 and employment conditions steadily improved with the growth of the trade union movement.

It is true that Manchester did not achieve parliamentary representation until 1832, but the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 was a Mancunian victory for the people of the nation. Mike Leigh’s film makes ‘Peterloo’ part of a bigger transnational history of the struggle of working people for political representation.

Featured image: A still from Mike Leigh’s film ‘Peterloo’, released in November 2018. It shows the popular orator Henry Hunt, played by Rory Kinnear, speaking at the St Peter’s Field protest, in Peterloo. Photograph © Simon Mein

This review was originally published in the Times Literary Supplement. You can read the original review here.

You may also like to read:

Emily Brontë’’s Fierce, Flawed Women: Not Your Usual Gothic Female Characters

Teaching Literature in the Age of Trump and Brexit: Some Reflections

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.