by Faten Hussein and Neil Vickers in conversation

Faten Hussein (FH) is a LAHP-funded doctoral researcher in Comparative Literature and the Medical Humanities at King’s College London. Her research investigates representations of illness in Arabic literature. She is specifically interested in what literature reveals about cultural and social attitudes towards illness, and the political, social, and economic determinants in access to health. She is about to take up a fellowship with the House of Common’s International Development Committee, through the Parliamentary Office for Science and Technology (POST).

Dr Neil Vickers (NV) is Reader in English Literature and the Medical Humanities at the Department of English, and co-director of the Centre for the Humanities and Health. He is associate editor of the journal Medical Humanities, published by the British Medical Journal group.

NV: Hello Faten. It’s a real privilege to be able to discuss your work with you, and to bring it to wider public notice through this blog interview. Why don’t you begin by telling our readers what you work on?

FH: I work on written accounts of illness from the Arab world. These can be fictional or autobiographical and in any form, so long as illness has a central place in them.

NV: Is that your definition of what an illness narrative is: any piece of writing that appears to be driven by a biographical or an autobiographical impulse, in which illness looms large?

FH: To keep it simple: yes!

NV: Good! How did you get into this field?

FH: I worked in politics for a number of years before coming to do my Master’s and PhD here at King’s, and I always wanted to find a subject that would enable me to use my love of literature to address a topic that mattered deeply to me. Illness narrative does this. Everyone we know falls ill at some point in their lives. Illness as a subject of research has policy implications, as well as implications for literary theory. And I like that about it.

NV: Can you say a bit more about what you are finding it’s like to be ill in the Arab world? Obviously a great deal has been written in Western illness narratives and in the scholarship surrounding them about what it’s like to be ill in the West today. Is it easy to draw lessons from that work to the situation in Arab countries?

FH: Yes and no. I work mostly on Egyptian narratives and there you run up against some of the same issues that you face here: illness affects your sense of your identity, family and friends re-evaluate your position in the world – that sort of thing. However, Egyptians experience illness in a much more politically repressive context than anything you have to contend with here for example, and this shows in the narratives I am reading.

NV: So you can’t talk about illness without talking about ‘illnesses’ of society?

FH: It would be very difficult. Lots of Arabic authors use illness as a metonym for the diseased state of society in general. Shirine Hana’i’s Tughra, for example, exposes the ugly side of biomedicine in the city of Cairo, where pharmaceutical companies test drugs on the bodies of the poor – the most vulnerable – with the blessing of the government (which obviously gets its share, as the author points out). Recently, issues like the monopoly of international pharmaceutical companies over 60% of medical provisions have been raised by Dr Mona Mina, the Secretary General of the Egyptian Doctors’ Syndicate.

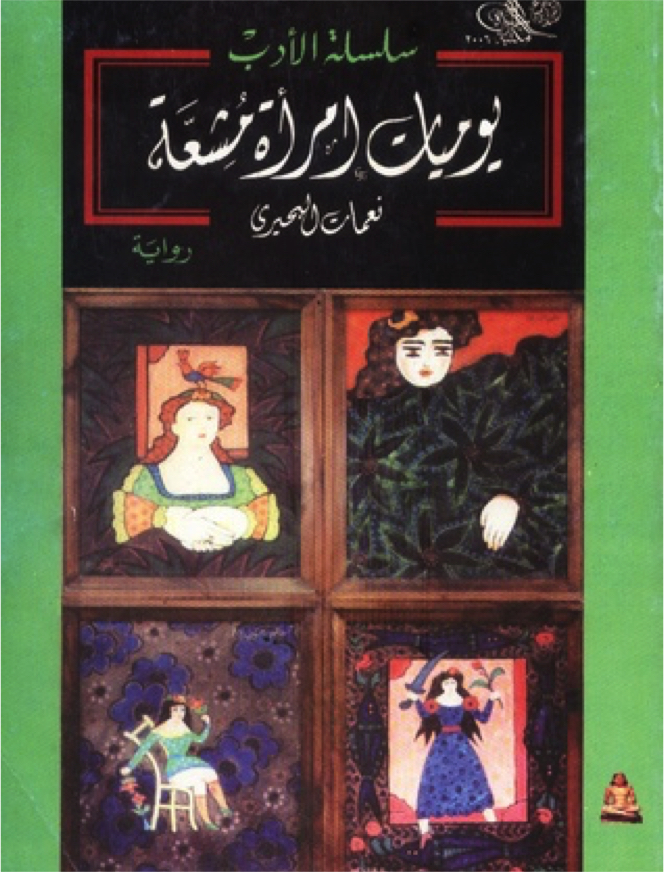

Other authors use illness narratives to speak about specific problems. Ni’mat al-Bihiri had breast cancer. In her memoir, Diary of a Radioactive Woman she describes how as a woman her body has always been an object of attention and blame in what she portrays as a chauvinist patriarchal society.

As a teenager, her developed breasts were an object of envy, but were also cause for anxiety and vilification. She rejected them as a burden attracting too much male attention, and used to hide them behind her schoolbag as if they were ‘a congenital deformity’…

Al-Bihiri despises the role society allocates to her as a woman, and talks about herself as ‘a piece of meat for men to devour’. Anyone who is following the sorrowful news on the increase in harassment of women on Cairo streets would relate. She uses her breast cancer to describe the effect of growing up in a society which offers no opportunities for women to be seen as equals: for instance, she couldn’t sit at the same dinner table as her father and brothers, and ate their leftovers. She speaks of her malnutrition as a child as a result, which she thinks led to her having a weak body susceptible to disease.

Western theorists of illness like Anne Hunsaker Hawkins or Arthur Frank or G. Thomas Couser typically hone in on the way ill people respond to biomedical reductionism: the individual rails at being reduced to a disease category. This is not the main issue in Arabic narratives, although some authors express feelings of frustration at being reduced to mere numbers.

The real issue is that illness is just one reduction in a series of reductions they face through life…

I study some doctors’ narratives too, and doctors draw attention to the same issues as patients in the memoirs they write – from dwindling health services to lack of access for the poor. Although patients are often chary of the idea that doctors might be on the same side as they are, they know that doctors face the same shortages, the same social handicaps.

NV: Tell me about access to healthcare.

FH: In Egypt, broadly speaking, there is a massive gap between the vast majority of the population which barely makes a living and a small number of very rich individuals, and of course there is a middle class which I would find difficult to define properly in this short space! But let’s say they are ‘doing all right’. Constitutionally, education and healthcare are both free or largely subsidised, but that’s just on paper. Try and seek treatment and you’ll see how hard it is to be treated in a government hospital: there are power cuts, endless queues, and patients’ families often need to learn to operate medical equipment themselves, which is dangerous.

Further out from the city it’s much worse, and women have less access to healthcare than men, particularly in the villages, where the burden on the family of a journey to the nearest clinic compels women most of the time to keep their illness to themselves until it is too late. If you want to get proper healthcare, you need to be able to pay.

NV: So what do you think the significance of your research is? You talked earlier about it having policy implications, but what kind of policy implications? It’s very unusual for a literary thesis to make claims of this sort.

FH: If you want to bring about a change in government policy, you need to take account of many viewpoints. If you set up a parliamentary inquiry into the provision of health care, for example, you will solicit expert testimony and evidence from doctors, patients, hospital administrators and others. This may provide facts and figures that could undoubtedly bring about positive change.

However, to generate public pressure, which is important in bringing about policy changes, you need personal stories that people can relate to. The books I look at do just that. They express a point of view that is deeply anchored in society but seldom voiced so openly.

Reading these stories, and bringing them to public attention, is a first step. I do not yet have a full conception or plan for using my research findings to inform policy after finishing my PhD, as I’m focused on finishing it at the moment! But it is something that has always been part of my thinking, and I will seek to do just that in my post-PhD work. My upcoming POST fellowship is the right place to explore these options.

NV: What you’re saying really interests me because previously we have discussed how illness narratives can be seen as almost treasonous, because they entail the risk of indicting your country.

FH: I think they are! Most memoirs I read include direct or indirect indictments of the state for failing to provide citizens with a dignified life that they could value.

Illness is just but one facet of that undignified life, and sharpens the writer’s sense of injustice…

NV: Which policy priorities take precedence over health in Egypt, say? I ask because you might think it would make sense for General Sisi and his administration to legitimise itself by making healthcare a priority.

FH: I don’t know. At the moment security seems to take precedence over everything! I’ve thought very hard about this question. Foucault said that the nineteenth-century European states used biopower to legitimise themselves. They introduced large-scale public health measures and limited free education. They justified their existence as the state while optimising the productive value of individuals. A historian friend of mine says that the only thing the state in Egypt really cares about is the wellbeing of the army. It is telling that the army has its own separate military hospitals.

NV: Ah so it’s like America – with its equivalent of the Veterans’ Association?

FH: It is much more wide-ranging than that. The Egyptian army is like a state within the state. They have their own construction companies, their own factories, their own share of the economy… they sell to the Egyptian people! I also wonder if they choose not to improve the lives of ordinary Egyptians for political reasons.

If you’re preoccupied with meeting basic needs – getting the next meal in, sending your kids to school, dealing with a healthcare problem – you won’t have time for political protest, nor will you think of higher ambitions. That’s good from the army’s point of view, I guess, because it keeps the elite in place. But I must admit, I don’t know how long this can last. There’s a massive young population. Why not capitalise on it? The same is true with the environment. Egypt has a very fertile landmass around the Nile but this has been allowed to degrade.

NV: The state within the state is not neoliberal then.

FH: They pick and choose from neoliberalism as suits them! That’s why I find it so hard to apply the Foucauldian bipower framework to certain aspects of my research. If those at the top of the state were rational actors, they would make better use of the biopower at their disposal, but they don’t! I am not saying that this should be done. I am just trying to find the logic underpinning the state’s behaviour in Egypt.

As many political analysts suspected, one reason why the army didn’t do more to keep Mubarak in place in 2011 was that he wanted his son Gamal to succeed him. Gamal was leading privatisation efforts in the government (he was the Deputy Chairman of the ruling National Democratic party), which was going to reduce public sector dominance, and the statist model of economy started under Nasser. His moves were seen as politically motivated, as it wasn’t clear how his plans would benefit the people, or whether privatisation would be accompanied with proper regulations and market competition.

This is not the point, though. The point is that the army viewed his ascent with deep anxiety. Gamal would have been the first civilian president since the 1952 revolution when the army took over governing Egypt. For the first time, the army would not have one of their own in power, looking after their interests. So, they were quite happy to see Mubarak go and prevent Gamal from taking power.

What we are seeing is that the army is not open to trying out any system that may relinquish the power of the state over the economy and people, so long as the state equals the army! A question I keep asking myself is: what makes it easier/better from the army’s point of view to maintain control by oppression rather than develop the individual (by investing in healthcare and education) and make maximum use of him/her, even if it were just for the army’s own advantage? I’m still trying to work this out, as you can tell!

NV: Sounds like you’ve got a very important book on your hands. I’m starting to see your thesis in a new light now. It seems really to be about how far healthcare can become a vehicle of hope for social change. Is that fair?

FH: I really can’t see it any other way at the moment.

Provision of adequate health care can only be seen as part of a much needed wider socio-political-economic change, which should shift the trend of privileging the rich over the poor when it comes to access to basic services.

NV: Wow. You’ve given us a lot to think about there. Thanks so much for this talk.

FH: Thank you for talking the time to talk to me about my research!

__________________________________________________________________________

If you are interested in knowing more about this field of research, please contact Faten Hussein at faten.hussein [at] kcl.ac.uk and Neil Vickers at neil.vickers [at] kcl.ac.uk.

The featured image is reproduced from https://aawproductions.wordpress.com/2015/02/21/iconoclastic-islamic-art/. Photograph © Tanya Singh.

You may also like to read:

The long read: Just Women and Violence

Confessions of a Medical Humanist

Book Review: Thinking in Cases

__________________________________________________________________________

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.