By Fran Allfrey, LAHP/AHRC-funded PhD student in the English Department

‘The traveller to Sutton Hoo must make two kinds of journey: one in reality and one in the imagination. The destination of the real journey is a small group of grassy mounds lying beside the River Deben in south-east England. The imaginative journey visits a world of warrior-kings, large open boats, jewelled weapons, ritual killing and the politics of independence’

Martin Carver, Sutton Hoo: Burial Ground of Kings?

The travel gods were against us. The trip to Sutton Hoo, Suffolk, usually takes about two hours from London. But on this day in March, our journey took over three hours and involved a ride to the end of the London Underground, a coach, two trains, and a twenty-minute trudge uphill.

https://vine.co/v/iXPgzJEXAqi

Sutton Hoo is the most important early medieval archaeological site in England, an Anglo-Saxon burial mound which is today complemented by an exhibition hall and tearoom complex owned by the National Trust. The famous ship burial buried underneath the largest of many barrows at the site in the seventh century were discovered by Edith Pretty and Basil Brown in 1939. These treasures have since been on display at the British Museum, gifted by Edith to the nation in an act of generosity not matched before or since. But it wasn’t until the new millennium the National Trust opened the Suffolk site officially to the public for the first time.

So. Why had Dr Josh Davies and I coerced a group of third year Beowulf students to spend the best part of their Saturday on public transport to go to Sutton Hoo? The thought did cross my mind several times: on the overly-hot coach; on the creaky, power-socket-free slow-train; once more when the hail came down between Melton station and the National Trust site.

https://vine.co/v/iXPHTQTVHHL

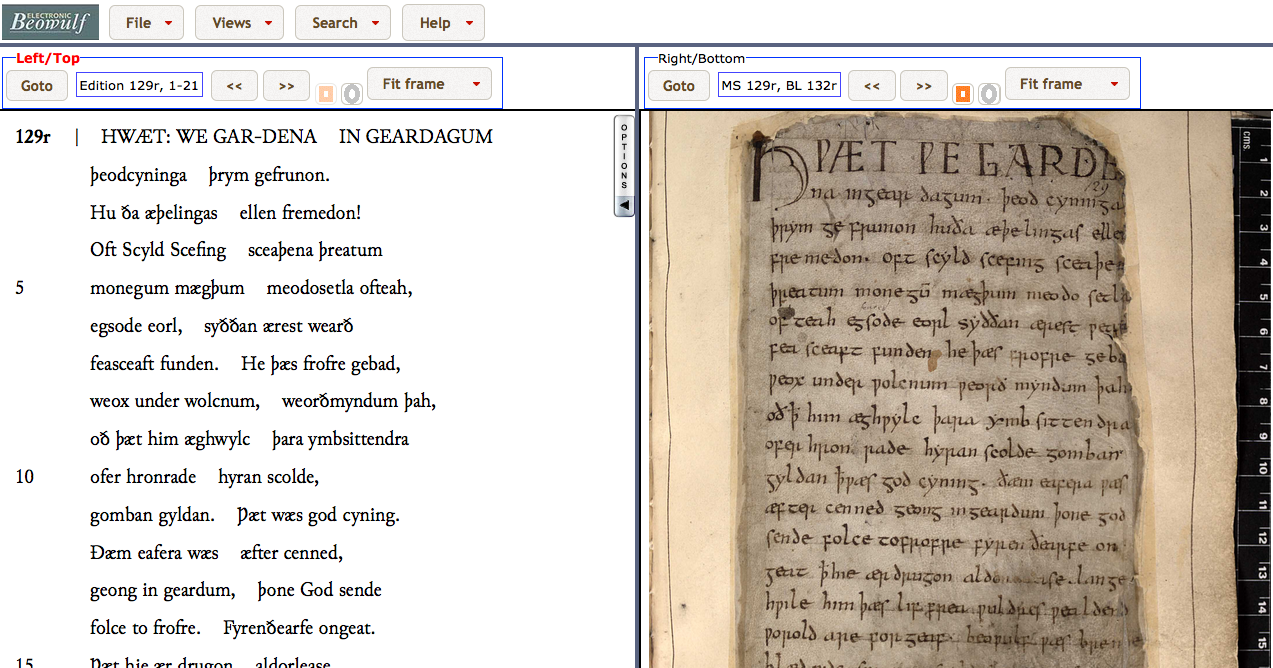

Well, the story goes that, in a crowded village hall at Sutton Hoo in August 1939, Beowulf (an Old English poem extant only in a tenth-century manuscript that you can see at the British Library), was called upon as evidence at the coroner’s inquest. The inquest had to decide whether or not the treasure had been put into the ground deliberately, never to be recovered. If it had been, then the treasure would belong to the finder. The poem, and particularly its final scenes in which the hero is buried in a barrow surrounded by amazing wealth, seemed to prove that the buried goods at Sutton Hoo were indeed never intended to be reclaimed by their owner, and so they belonged to Edith Pretty. Since then, Beowulf and Sutton Hoo have become ‘the odd couple’, as Roberta Frank has dubbed them, related to each through historical and academic circumstance and practice, even if their precise relationship is unknown and unknowable.

https://vine.co/v/iXPpeIuzUle

This semester, conversations in our Beowulf class have looped and centered and dodged around questions of authenticity (what do we mean when we talk about the original poem, when we talk about a text supposed to have come from an oral tradition perhaps hundreds of years before it was copied into the tenth-century manuscript in which it survives? what do we make of editorial ‘corrections’ to the manuscript?); of materiality (what remains? what can the damaged, messy manuscript tell us? how might looking at the objects found at Sutton Hoo help us?); and of how we might know about the past through poetry (was it written down as history, as fantasy, as propaganda?).

We’ve wondered about how we might not be able to talk about the ‘Anglo-Saxon World’ with any certainty if we use the poem as evidence. But we’ve agreed that we can talk about what the poem thinks, what the poem wants, and we can explore the physical form(s) the text now takes. We can think through what the poem has to teach us about history, time, memory and identity, and we can examine what its translation and study today might tell us about the Anglo-Saxon world and the modern imagination.

https://vine.co/v/iXPTKZ0L3W0

So much else seems to slip away from our grasp (who wrote it? Where? Why? Who copied it into the manuscript? Why did the manuscript survive): we must always remember to return to the text that remains, the somewhat tatty manuscript that was made by unknown scribes, for unknowable reasons.

We came to Sutton Hoo because it’s another thing that remains, that scholars and museums, including the National Trust, continue to put into dialogue with the Beowulf poem. Like Beowulf – an idea that can indicate a lost oral composition, manuscript text, so many printed editions, translations, films – Sutton Hoo’s meanings are multiple, imprecise and situated, defined by the experiences and expectations of those who travel there. And, like Beowulf, Sutton Hoo is defined by what we don’t – and won’t – know: who was buried there, why and when?

https://vine.co/v/iXPU6BHduXm

In my research, which explores the meanings of Anglo-Saxon culture in the modern world, I’ve become obsessed by the writing of members of the Sutton Hoo Society (a voluntary organisation set up in 1989 to raise money for on-site archaeology and maintenance, before the National Trust got involved) and their recollections of what being at the site feels like.

There’s something about spending time at Sutton Hoo that people feel changes their understanding of the past. As one volunteer wrote in Saxon, the Sutton Hoo Society newsletter: ‘Our lives were marked by the character and setting of the landscape of Sutton Hoo. On weekend afternoons standing on a windswept plateau overlooking the River Deben one would step back into a world of 1400 years ago: [the place played its] part to thrill the senses and conjure up atavistic notions.’

https://vine.co/v/iXPxzjDFezA

So, as part of our work with the poem and its unknowable depths, we travelled with the students, via bus replacement services and through the wind, rain and hail, to this distant site. Not because we expected to find anything (because all the ‘treasure’ is in the British Museum after all), but to think through the experience of journeying together and thinking together in this place.

https://vine.co/v/ipeP7QLdZ1e

Thank you to all the students that came along and shared their thoughts and stories (and train snacks) so generously, and thank you to the English Department for the provisions that kept us going on our pilgrimage!

References

Martin Carver, Sutton Hoo Burial Ground of Kings?, (British Museum Press, 1998), p. ix.

Roberta Frank, ‘Beowulf and Sutton Hoo: The Odd Couple’, in Calvin Kendall and Peter Wells, eds., Voyage to the Other World: The Legacy of Sutton Hoo (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1992), pp. 47-64 (47).

Andrew Lovejoy, ‘Guiding and Sutton Hoo 1984 – 2002’, Saxon 39 (2003), 3.