An open drafting process of ‘Capoeira Boy’ from Ruth Padel’s collection, Learning to Make an Oud in Nazareth (Chatto, 2014).

Introduction

by Penny Newell

Sometimes poetry mutters, sometimes it sings, oftentimes it catches our eye and looks. There’s a line from a poem of Ruth Padel’s collection, Learning to Make an Oud in Nazareth (Chatto, 2014), which manages all three. It runs: ‘I am looking too hard, or this scene is looking too hard/ at me.’

You need only read the commentary below to realise that here we overhear the poet muttering to herself, pen and notebook in hand. Yet we also hear a clue to the song that Padel plays on the oud. The oud is both the instrument, and perhaps a Middle Eastern homonym of the ode (from the Greek ’αοίδη [aoide], ‘a song’). The oud is a solemn song, sung by a chorus of CNN, Youtube and eBay, refugee camps and tanks. Last week, Jo McDonagh and Rowan Boyson asked ‘How might the humanities contribute to an understanding of the current refugee ‘crisis’?’ Padel’s poetry is alive to this question. The poems of this collection catch our eye with it, and let it look at us hard.

Below, the illuminating drafts of ‘Capoeira Boy’ show us the process that a poet goes through to allow poems such powers. At times, this is a nerve-wracking read. Words and phrases that you cherish (‘thistle-light acrobalance’) surface, and teeter on non-existence. Other times, this process is utterly relieving. You breathe with Padel when the poem breaks out of its 10-line stanzas. Throughout, this is a process that shows a poet finding a balance of sight and insight. Or a poise of question and statement, through which the poem sings.

On Writing and Revising a Poem

by Ruth Padel

Whatever it is, that odd process we call “writing a poem”, it’s different for every poet, maybe for every poem.

Some poets get the rhythm before anything else.

Some poems begin with a phrase or image.

Sometimes lines come word by word over weeks, even years.

Sometimes a lot comes all in a rush, and then stalls.

Based on the way I tend to work, I sometimes suggest to students it can be useful to think in terms of two different ways of making sculpture.

At first, when you are getting the poem down, trying for a first draft, you might get involved in what people sometimes call researching. But “research” sounds active and this process can be pretty passive: like standing motionless in a forest, opening yourself to every sensation, every wind, rustle, fall of a leaf. Every tiny thing you hear, see or feel might be important. “Research” can mean an utterly tense, still, waiting, silence. You’re waiting on the outer world, holding yourself abnormally aware and open to 365 degrees of concrete things, but also on your inner world, letting associations, memories, thoughts float into your imagination.

At this stage, the reception and gathering moment, you’re like a sculptor working in soft material like clay or wax, or trawling for bits and pieces to collage. It’s very exciting: anything you meet or think or remember may be relevant. Everything can come in – until you have a draft.

Then a gelling or hardening sets in. The poem exists and has its own presence. Now, what you have to listen for is what it needs.

You become a different sort of sculptor, no longer gathering in but chipping away, freeing the image in the stone. There’s the block of marble – and you have to carve away everything that mutes or dulls the poem, stops it being its own best form.

I can see myself doing that with a poem called ‘Capoeira Boy’, which now ushers in the last third of my collection Learning to Make an Oud in Nazareth but was I think the last one I wrote for it.

I knew I had on my hands a book about the Middle East and creativity. Palestine, Israel: holy land with a geological rift, and a sense that humanity itself is rifted. The heart of the collection would be a sequence on the Seven Last Words of Christ on the Cross. Then someone happened to mentioned capoeira, the dance that is also combat. I looked it up online. The first thing I saw was on You Tube: dedicated members of an international NGO called Bidna Capoeira teaching kids in a Palestinian refugee camp to dance. Learning capoeira gives these pent, traumatized children not only physical skills, achievement and well-being, but social ones: a community sense, new powers of give and take, and above all self-esteem.

Portuguese friends told me more about the history of the dance. Capoeira began in Brazil. It is the name of a kind of tall grass. African slaves there were forbidden by their “owners” to learn or practise combat, or to carry or use weapons. But they weren’t forbidden to dance. So they evolved a dance which is also a form of practising combat. They cleared a ring in tall grass – not to be seen – and everyone stood in a circle, the roda, watching two dancer-combatants, in the middle.

Capoeira is popular today in the west. If you watch on You Tube you can see the swipes are really savage: its art is the grace of mutual evasion as well as attack. Your opponent is also your partner.

I suddenly felt this art of lethal tussle, of self-hood, mirroring and interdependence, belonged in my Palestine book. And anyway, the dance I saw was set there – in a refugee camp. I needed this poem – if I could get the tone right.

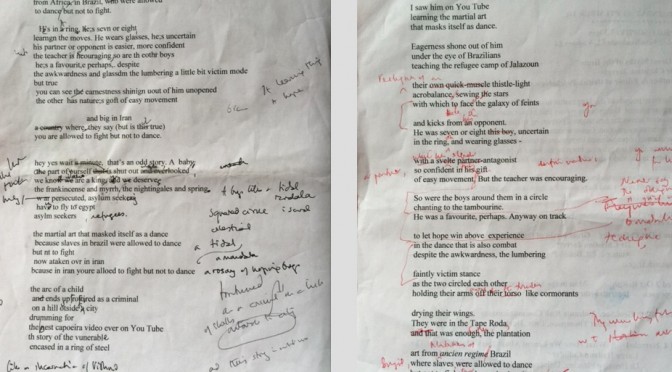

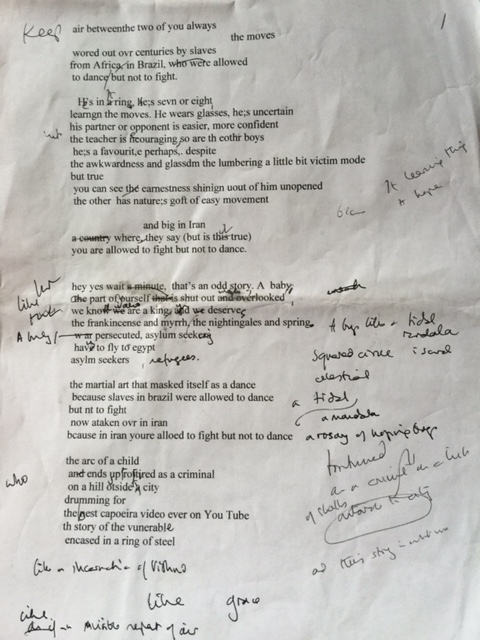

Capoeira Boy early draft is a page from the first phase, when everything was coming in. A lot of things in it didn’t make it into the final poem: asylum seekers, the three Magi, an incarnation of Vishnu, and the importance of capoeira in Iran. (Where, someone told me, you were allowed to fight but not dance, the opposite of the slaves’ experience in Brazil.) But the core is there, watching a particular boy learn to dance. And so is the tone. A speaker who is not pretending to be there, who doesn’t know much, and yet, watching on You Tube, the speaker feels engaged with the boy, worried for him.

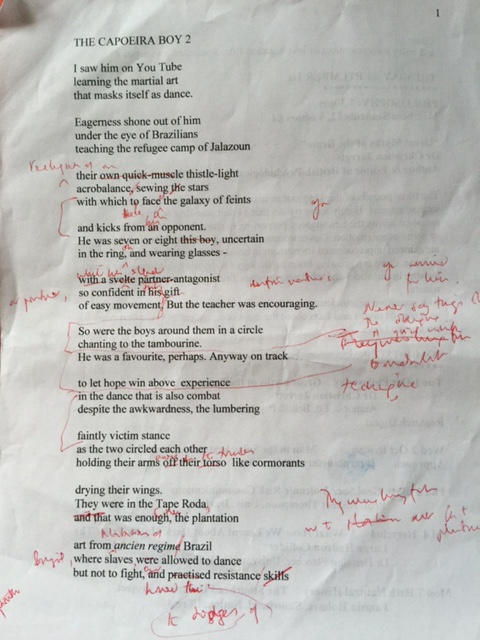

In Capoeira Boy 1, the poem is trying to settle into stanzas of three short lines, with 2, 3 or 4 beats in each. But it’s not working. A stanza, to be a stanza, has to have its own integrity, its own reason for being a unit. Looking back, I can see the poem, like an animal refusing the wrong food you try and give it, is telling me something: it is saying, Junk the three liners. Something about them doesn’t fit this musical canvas which is built round a longer phrase or unit of thought than I realized at first.

Plus there’s a lot of stuff in this version that needs to go.

In the next version I am still using three liners and those stilted short lines. I haven’t been listening hard enough to what the poem was saying.

THE CAPOEIRA BOY 3

I saw him on You Tube

learning a martial art, the fight

that masks itself as dance.

Eagerness shone out of him

under the eye of Brazilians

teaching children of Jalazoun

Refugee Camp the thistle-light

acrobalance

of self-defence

and the back-and-forth, foot-to-foot ginga

for leverage

to face the galaxy of kicks and swipes

you expect from an opponent

and to leap, spin, skim, soar, feint

with him like firebirds among the stars.

He was seven or eight

this boy, wearing glasses

with a partner-antagonist so confident

in nature’s unfair gift

of easy movement!

But the teacher was encouraging.

So was the ring of boys

chanting to the tambourine.

Watching, you worried for him

at least I did, but I saw he was loved.

A favourite perhaps, or anyway on track

to give hope a chance

over experience

in the dance that is also combat

despite the awkwardness, the lumbering

faintly victim stance

as the two circled each other

holding their arms off their trunks

like cormorants

drying their wings.

They were in the Tape Roda! They knew

it was ancient and strong

and came from the old plantations

of Brazil, where slaves

allowed to dance but never fight

wove a resistance

strategy disguised as acrobatics –

now big in Iran

where they say (but is it true?)

you’re allowed to fight but not to dance

and taught to kids like them in Palestine

where blocks of gold sunlight

press on the No-Go Zone

behind the wall.

I saw him on You Tube

in a refugee camp of Hebron

learning the fight

that masks itself as dance.

They were having fun.

The tutor, laughing, taped

a circle on the beaten ground,

and handed out instruments –

pandeiro, atabaque drum

and silver bells. He was young

himself, he supervised the falls,

blows, cat’s whisker escapes.

Out of each other’s way! Attack

and spin – it’s a rhythm thing –

on your haunches in sync

and flat on your hands. Aim your kick

in his face, let him duck.

Air-somersault, back-roll,

cartwheel and flip. This is all about you

but you can’t do without him. Headstand,

loose-limbed and free

as in the no man’s land

outside Damascus, the Al-Tanf

camp for orphans

displaced by violence

where capoeira began for refugees

then spread to the West Bank

teaching tolerance:

how to contain

the waves that break

inside you. Let them melt into foam

like a ghost of the Milky Way

and be done with

while the six-lane highway

next door, shaking the camp

with its vibrations

brightens its lamps

and on the other side

the twenty-foot raw cement

wall leans like a stage-set

for Macbeth.

I saw lemon-blossom in the distance

on a hill black with tanks

where I guessed his father was born

and would never set foot again.

As the boy settled into a dance

like the sparring of Orpheus with Death

I pictured the black flame

of a split aorta

in his father’s chest –

a man who’d lived his grown-up life

in a camp

and would die in one now.

The heat of afternoon

flowed like the midday daemon

through lines of canvas tents

like mist coming off black jade

as each boy became

the other’s mirror.

They were twin lights in a sconce,

panther cubs perfecting life-skills

in dark rays of the jungle:

timing and speed, the weave

of twisted threads for the roda

of life, each pitting all he was

against the other

in the little space

between self’s flying heel and other’s face.

By the fifth draft, I’ve got the message. Not three liners. And longer lines, please. But with six line stanzas the simplicity, which sprang from my sense of these young eager boys, has gone. So has the poem’s sense of space, which in the earlier draft tried to mirror the capoeira’s own cleared circle where the dancers/sparring partners move.

And I’ve imported other unecessary things, like Orpheus and Death. And it’s all too dense. Too many adjectives – and several phrases are too explainy. People come to poetry not for explanation but to meet a question, or a suggestion, a possibility and a resonance. Or for the flick of the tail of some important thing they want to go on wondering about afterwards.

CAPOEIRA BOY 5

I saw him on You Tube, learning the martial art

that masks all our fights as dance. Thistle-light

acrobalance, and back-forth foot-to-foot ginga

facing the galaxy of kicks and swipes you expect

from an opponent. How to spin, soar, feint

and tarentelle with your brother among the stars.

I saw he was loved. A clumsy favourite, perhaps.

Loved enough, anyway, to give hope a chance

in the dance that sings, that is combat

despite his lumbering faintly victim stance

as the two circled each other, holding their arms

off their trunks like cormorants drying their wings.

He was seven or eight and in glasses. Eagerness

shone out of him in the ring of boys chanting

to a tambourine. They knew this dance-fight,

now big in Iran where you’re allowed

to fight but not dance, came from slaves allowed

to dance but not fight. And that kids like them

on the West Bank could learn it in Hebron.

I saw him on You Tube, in Jalazoun Refugee Camp.

The teacher, laughing, encouraging, supervised

blows, falls and slips, cat’s whisker escapes. Flat

on your hands! Squat and spin, aim your kick

in his face. Let him duck. And then cartwheel away.

This is all about you but you’re nothing without him.

Dance sets you free. Free of the six-lane highway

shaking the camp with vibrations. Free

of the twenty-foot wall of cement, a stage

set for Macbeth. I saw olives flutter on amethyst

hills where I guessed his father was born. As the boy

learned the sparring of Orpheus with Death

I pictured the black flame of a split aorta

burn in his father’s chest. Who’d lived his days

in the camps and would die in one now. I saw the heat

of afternoon flow through passage-ways

between tents like mist coming off black jade

as each lad became the other’s mirror.

They were twin lights in a sconce, panther cubs

perfecting life-skills. Timing and speed,

the weave of twisted threads for the roda

of life, each pouring all he was in the little space

between self’s flying heel and other’s face.

In the seventh draft, I see I tried to put it back into three liners, but with longer more flowing lines.

CAPOEIRA BOY 7

I saw him on YouTube learning the martial art

that masks fighting as dance; the rocking, foot-

to-foot ginga bracing him for kicks, swipes

and thistle-light acrobalance. He was finding how to spin,

feint, soar with his opponent. You could worry about him,

at least I did, but I saw he was loved. A favourite

perhaps. Enough anyway to give hope a chance

despite his lumbering, faintly victim, stance

as the two circled each other, holding their arms

off their torsos like cormorants drying their wings.

He was seven or eight, wearing glasses. Eagerness

shone out of him inside the ring of boys

chanting to a tambourine. They knew slaves in Brazil

made the rules. Only by dance do you learn how to fight.

Only by fight how to dance. And also that kids like them,

on the West Bank, could learn this in Hebron.

I saw him on YouTube in Jalazoun Refugee Camp.

The teacher, laughing, supervised falls, accidents,

cat’s whisker escapes. I imagined he was telling them

Squat and spin! Flat on your hands! Aim your kick in his face –

let him duck – then cartwheel away. This is all about you

but you’re nothing without him. Let the dance-fight-dance

set you free. Free of the six-lane motorway

shaking the camp with its sorrowful vibrations.

Free of the twenty-foot wall of cement, a stage set for Macbeth.

Grey olives flickered beyond, on hills where I guessed

older men like his grandfather were born

and are forbidden to graze sheep or tend their trees again.

While the boys danced, I pictured the flame of a split aorta

in the chest of a man who has lived all his days in the camps

and will die in one now. Afternoon flowed

through rows of tents like mist coming off black jade

as each became the other’s mirror. They were twin lights

in a sconce, tiger cubs perfecting life-skills – pounce,

timing, split speed for the roda – each pouring all he was

into the little space between self’s flying heel and other’s face.

In each draft, I see I’m trying to bring new things into focus, like the boy’s father, his caged life in the camps, the sight of his own unreachable olive trees.

But the three liners still don’t feel right. Why didn’t I hear? The first lines of stanzas 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 10 and 11 all belong with the last line of the preceding stanza – it’s wildly obvious but I am still not going for the obvious solution. The phrasing was telling me: this poem’s natural form is quatrains! Instead I went to the other extreme. Draft 8 has stanzas of ten lines. It’s as though I’d got the journey of thought clear but something was stopping me understanding the separate stages or stations.

Plus I’m trying to say too much now. I’m not letting the silences work, letting the poor poem breathe.

Capoeira Boy 8

I saw him on You Tube, learning the martial art

that masks fighting as dance. Thistle-light acrobalance,

the rocking, foot-to-foot ginga, bracing him

for kicks and swipes. He was learning how to spin,

feint, soar with his opponent. You could worry

about him, at least I did, but I saw he was loved,

a favourite perhaps, anyway enough to give hope a chance

despite his lumbering, faintly victim stance

as the two circled each other, holding their arms

off their torsos like cormorants drying their wings.

He was seven or eight, wearing glasses. Eagerness

shone out of him, inside a ring of boys

chanting to a tambourine. They knew slaves in Brazil,

allowed to dance but not fight or bear arms,

made the rules. Only by dance can you learn how to fight.

Only fighting can you dance. And also that kids like them,

on the West Bank, could learn it in Hebron.

I saw him on You Tube in Jalazoun Refugee Camp.

They were having fun. The teacher, laughing, supervised

blows, falls and slips, cat’s whisker escapes.

I didn’t get the Arabic. But I imagined him telling them,

Squat and spin! Flat on your hands! Aim your kick in his face –

let him duck – and cartwheel away! This is all about you

but you’re nothing without him. The fight-dance

sets you both free. Free of the six-lane motorway

shaking the camp with its sorrowful vibrations. Free

of the twenty-foot wall of cement, a stage set for Macbeth.

Olive trees flickered behind, far off, on blue hills

where I guessed the old men, maybe even his father,

were born: and are forbidden to go, or tend the trees, again.

As the boy learned, I pictured the flame

of a split aorta burn in the chest of a man

who has lived his grown days inside camps

and will die in one now. I saw the heat of afternoon flow

through miles of canvas tents, like mist coming off black jade

as each lad became the other’s mirror. They were twin lights

in a sconce, panther cubs perfecting life-skills.

Timing and speed, the weave of twisted threads for the roda

of life, each pouring all he was into the little space

between self’s flying heel and other’s face.

It’s all too clumpy and dense. It loses the lovely young agility of the boys enjoying their moves which was really where the poem began.

At last the penny dropped. Keep the sense of space, keep the flowing lines, but chip away the extraneous stuff. Let the poem live in the open – to fit the capoeira’s origins in the grassy plains of Brazil, and the open air Palestinian camp. But, as with a sculptor facing a block of marble, the hard thing is to know exactly what is extraneous. You don’t want to cut away too much. The final chipping and polishing may take years.

FINAL VERSION Capoeira Boy

(from Learning to Make an Oud in Nazareth, Chatto, 2014)

I saw him on YouTube. He was learning the martial art

that masks fighting as dance; the rocking, foot-

to-foot ginga was bracing him for kicks, swipes

and thistle-light acrobalance. He was finding how to spin,

feint, soar with his opponent. You could worry about him,

at least I did, but I saw he was loved. A favourite

perhaps. Enough anyway to give hope a chance

despite his lumbering, faintly victim, stance

as the two circled each other, holding their arms

off their torsos like cormorants drying their wings.

He was seven or eight, wearing glasses. Eagerness

shone out of him inside the ring of boys

chanting to a tambourine. They knew slaves in Brazil

made the rules. Only by dance do you learn how to fight.

Only by fight how to dance. And also that kids like them,

on the West Bank, could learn this in Hebron.

I saw him on YouTube in Jalazoun Refugee Camp.

The teacher, laughing, supervised falls, accidents,

cat’s whisker escapes. I imagined he was telling them

Squat and spin! Flat on your hands! Aim your kick in his face –

let him duck – then cartwheel away. This is all about you

but you’re nothing without him. Let the dance-fight-dance

set you free. Free of the six-lane motorway

shaking the camp with its sorrowful vibrations.

Free of the twenty-foot wall of cement, a stage set for Macbeth.

Grey olives flickered beyond, on hills where I guessed

older men like his grandfather were born

and are forbidden to graze sheep or tend their trees again.

While the boys danced, I pictured the flame of a split aorta

in the chest of a man who has lived all his days in the camps

and will die in one now. Afternoon flowed through rows of tents

like mist coming off black jade as each became the other’s mirror.

They were twin lights in a sconce, tiger cubs

perfecting life-skills – pounce, timing, split speed

for the roda – each pouring all he was into the little space

between self’s flying heel and other’s face.

Ruth Padel is Poetry Fellow in the English Department at King’s College London. Learning to Make an Oud in Nazareth is her tenth poetry collection.

Penny Newell is a PhD student in the English Department, and an editor of the King’s English Blog.

You may also enjoy

Swallow (early draft), by Nadia Saward