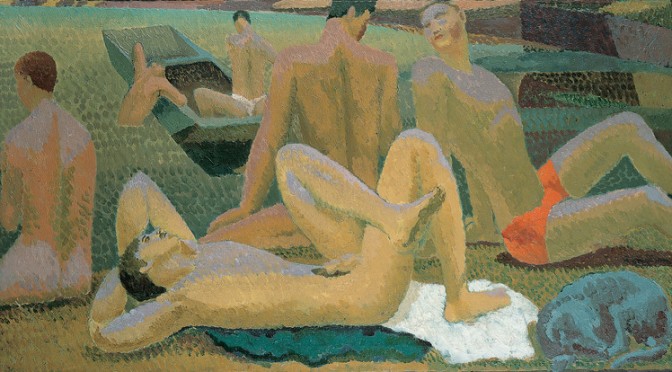

Featured image: Duncan Grant © Tate

by Ellie Jones, PhD researcher funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and Tate. Her thesis centres on expressions and perceptions of queerness and race in early twentieth century British art.

“Dearest, at this moment I would give my soul to the Devil if I could kiss you and be kissed.”

In the summer of 1908, the Bloomsbury artist Duncan Grant wrote anguished letters to his sometime lover and lifelong friend, the economist John Maynard Keynes. In the infancy of their romance, the pair had been forced to spend time apart while Grant holidayed with family friends, a period of separation which served only to deepen their emotional closeness. Absence, after all, makes the heart grow fonder.

Grant’s letters expose a longing for the comfort of commonality, the security we find in shared experiences. He needed the company of someone who understood what it meant to be a gay man living in Britain before decriminalisation in 1967. “How much I want to scream sometimes here for want of being able to say something I mean,” one letter reads: “It’s not only that one’s a sodomite that one has to hide but one’s whole philosophy of life; one’s feelings for inanimate things I feel would shock some people.”

These letters are revealing of the ways Grant linked his sense of alienation, at the hands of his sexuality, to a broader sense of difference relating to the way he perceived the world around him. He understood his queerness as a central organising structure of his vision and his personhood; his “whole philosophy of life”. By making an explicit connection between his sexual alterity and his way of seeing, he leads us to consider: in what ways do our sexual pleasures and fantasies inform the way we see the world?

This question, and the broader connections between art and diverse gender and sexual identities, takes centre stage in Tate Britain’s Queer British Art exhibition. The landmark show explores how artworks and objects can evoke the contradictory and overlapping experiences of queer intimacy and desire. It begins in 1861, when the death penalty for sodomy was abolished, and moves through the century to the partial decriminalisation of sex between men in 1967.

Some of the artists and subjects in the show were directly affected by legal persecution, including Oscar Wilde, Simeon Solomon, Radclyffe Hall and Angus McBean. At the same time, other artists encoded their sexuality and found innovative, playful and beguiling ways to express their queer identities and desires. In any case, the exhibition is revealing of how queerness resides at the heart of British art history, as well as some of its more obscure margins.

The Bloomsbury Group sit relatively comfortably within the canon of 20th-century British art and culture. The closely-knit network of artists and intellectuals was bound together by political ideals and personal affections, as well as aesthetic tastes, and together they stood firmly at the forefront of the British avant-garde until the outbreak of World War II.

Largely comprised of queer women and men, including the writers Virginia Woolf, Lytton Strachey and E M Forster, along with the artist Dora Carrington, the Bloomsbury Group was committed to the redefinition of personal relationships as they were understood and represented in pre-war England. They regarded the conventions of the previous generation with critical suspicion. Each associate of Bloomsbury sought liberation in sexual, social and artistic terms.

As Dorothy Parker’s famous remark goes, the Bloomsbury Group “lived in squares, painted in circles and loved in triangles”. Though she pursued relationships with women, Carrington loved and was loved by Strachey, who was almost exclusively attracted to men. Meanwhile, a select few of Duncan Grant’s male lovers made visits to Charleston in Sussex, where Grant lived in a domestic partnership with Vanessa Bell and her children.

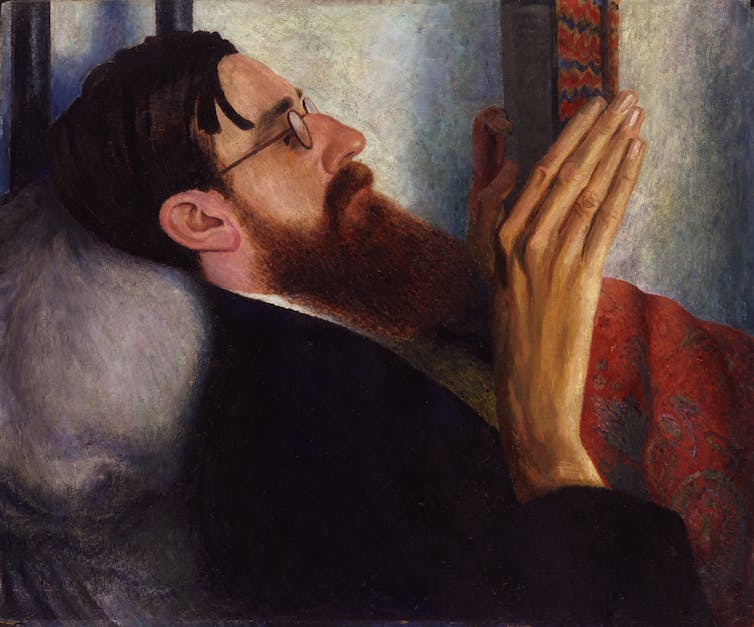

These unconventional lives and arrangements are immortalised in their artwork. Carrington’s Lytton Strachey (1916), for instance, captures the life Carrington and Strachey created at Tidmarsh Mill House, and latterly Ham Spray House in Wiltshire, where they lived with Carrington’s husband and Strachey’s object of desire, Ralph Partridge. Writing in 1921, Carrington addressed Strachey:

You never knew, or never will know the very big and devastating love I had for you. How I adored every hair, every curl on your beard. How I devoured you whilst you read to me at night.

Her encyclopaedic knowledge of his face, mapped out in the minutest detail, is betrayed in this extraordinarily attentive portrait, an intimate testimony to the love of her life.

The Tate’s show, which my research has informed, rightfully positions Bloomsbury at the centre of Britain’s queer history. The political, sexual and artistic frustrations motivating the artists of Bloomsbury to create still exist today, albeit in mutated forms.

From Virginia Woolf’s genre-defying Orlando to Duncan Grant’s private erotica, the objects Bloomsbury left behind speak on behalf of those whose voices have been silenced in the mainstream. Their queer art provides tender pockets of shelter in a still-hostile world, and their work ceaselessly reverberates with the force of resistance.

Queer British Art is at London’s Tate Britain from April 5 to October 1 2017.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article, and find King’s College London‘s full profile.

You may also enjoy Prize Winning Responses to Modernism, and Wax Virginia.

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and not those of the English Department, nor King’s College London.