The rate of children, teenagers and young adults reporting symptoms of anxiety and depression is higher than ever, with 18.0% of children aged 7 to 16 years and 22.0% of young people aged 17 to 24 years meeting the criteria for a probable mental health condition. The standard way to assess such conditions is with total scores on a symptom scale at a single point in time, so those with high scores can be identified and provided with extra support. However, this type of information often doesn’t tell us how symptoms are developing or changing over time. Importantly, it does not offer us the opportunity to target critical periods of mental health development in which we could intervene to stop symptoms increasing, or even better, intervene to make symptoms improve.

This intrigue is at the heart of longitudinal research, which aims to explore and analyse change over time within a person or a group of individuals. This data is collected by asking about the same symptoms, often via a questionnaire, within the same individual, over three or more time points. Historically, this type of information has been challenging to collect as it involves following participants up over time and asking them to fill out questionnaires in person or attend assessments. However, with the advent of the internet, and the use of online surveys and mobile apps, longitudinal data is becoming increasingly available to researchers across the globe. This offers immense opportunity to make inroads in mental health research and identify patterns of mental health that could be transformed into therapeutic strategies and interventions.

The majority of mental health researchers use longitudinal data to find out whether (and to what extent) the severity of symptoms are changing within an individual or between individuals. For example, researchers might be interesting in whether an individual’s symptoms are fluctuating over a fixed period (within person change), or whether symptoms differ between people, based on certain characteristics such as sex, family mental health history, school inclusiveness and many more.

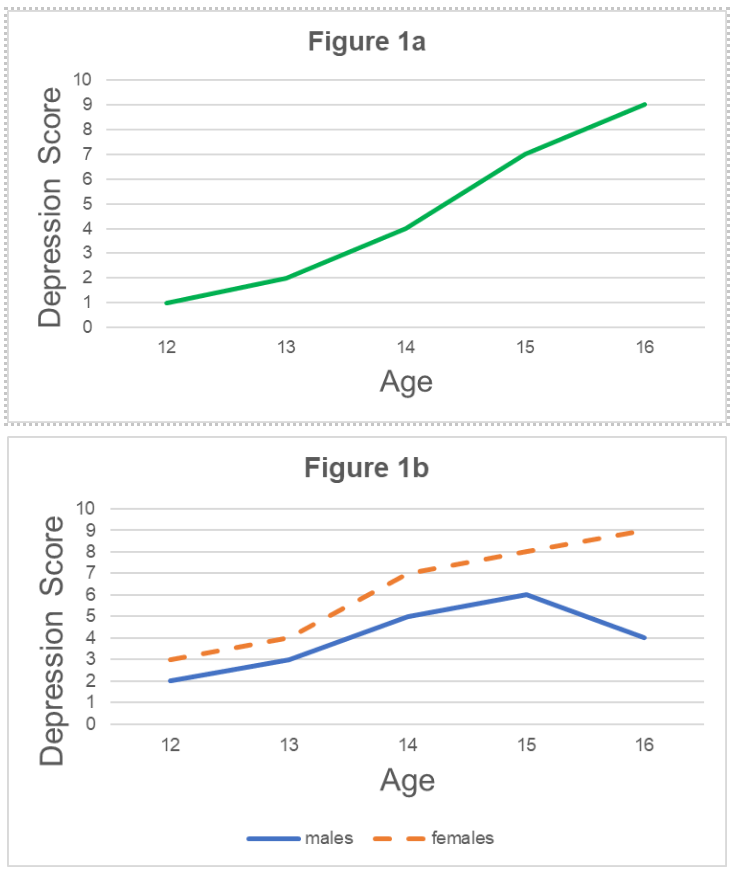

To visualise this type of change over time, longitudinal researchers tend to model and generate ‘trajectories’ (which represents the course of symptoms over a given period). For example, figure 1a displays an individual’s depression trajectory shifting from low to high over a 5-year period. Figure 1b displays a trajectory for males and females over the same period and shows that females have a much higher trajectory compared to males. These findings are important for developing interventions and support mechanisms for groups that might be at heightened risk of poorer mental health traits.

Note. These figures were created for example purposes only.

In addition, researchers can also obtain additional information from longitudinal data such as the age and speed at which symptoms are changing over time. This type of information is pertinent as it allows us to pinpoint critical or sensitive periods for when intervention or support might be needed most, and when it might potentially be most effective

Mental health researchers have been interested in this type of information for decades, however the tools required to explore or analyse this data can require specialist expertise and software. This can create a barrier for those looking to explore longitudinal data as researchers/or users may not have the time or capacity to learn and implement these skills. To combat this barrier, our team are in the process of creating a data tool (and stepped training component) which readily enables mental health researchers and users with longitudinal data to visualise their data and run models to assess and analyse within and between individual change. Thanks to funding from Wellcome, we are developing this too to create a starting point for applying longitudinal analytic techniques to repeated measured data and to highlight key periods of development that could be used to provide better support and treatment for at risk individuals. We want to ensure that anyone who has longitudinal data can have the tools to explore and analyse their data. We see this tool as being useful not only for mental health researchers, but also for any user who has longitudinal data and wants to visualise their data in a speedy and efficient manner. This could be anyone including, but not limited to: teachers, health professionals, clinicians and even charities.

With the recent availability of large longitudinal datasets with rich, repeated information on youth mental health, now is an important time in which mental health research can really flourish. We hope that this tool plays a part in facilitating future mental health research and look forward to sharing it with you all soon.