PhD student Katherine Thompson outlines findings from her recent paper investigating trajectories of social isolation.

Social isolation in childhood has been linked to a higher risk of experiencing mental and physical health problems in adulthood. It is unclear, however, if these outcomes are different for children who experience varying levels of social isolation as time goes on. Are there particular groups of children who follow different long term patterns of isolation? How does their level of social isolation influence their health when they become adults? And are there any factors in early life that we can be aware of that increase the risk of these children becoming socially isolated later on?

Social isolation occurs when there is an absence or lack of social relationships and interpersonal connections. As children, social isolation is experienced slightly differently to that of adults. As children often have parents or siblings around them, childhood social isolation can be conceptualised as the extent to which children are connected to other children. This is different to feeling lonely, as children can be lonely even when surrounded by other children. Childhood social isolation could be particularly detrimental to later health, as peer connections are becoming increasingly important, cognitive processes are rapidly developing, and mental health problems are becoming apparent. Previous research has shown that isolated children are at risk for depression, cardiovascular problems, low educational attainment, obesity, and even premature mortality in adulthood. However, limited research has assessed if particular children could be at risk of becoming socially isolated as they grow up.

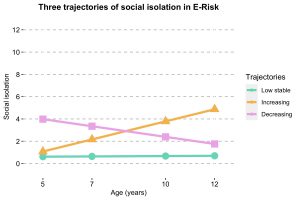

Using the Environmental risk longitudinal twin study (or E-Risk study) of 2,232 children, we showed that across ages 5, 7, 10, and 12, children can follow three different trajectories of social isolation. Some children do not become isolated at all (low stable group; 90%). Some children experience high levels of social isolation at the beginning of childhood but this decreases as time goes on (decreasing group; 5.25%). And other children are not isolated early on, but they become more isolated as they progress through childhood (increasing group; 4.75%).

We also found that children with particular characteristics were more likely than others to be isolated. For example, children with increased hyperactive and inattentive (ADHD) behaviours, and emotional problems were most likely to be isolated earlier on in childhood. Similarly, children who became more isolated as time went on were more likely, at age 18, to have increased ADHD symptoms, conduct disorder symptoms, feel lonely, be less optimistic about their career prospects, and be less physically active.

These findings provide new insight into the experiences of social isolation throughout development. Most children were not isolated, and for those that were, they shifted in and out of isolation over time. We highlight the complex associations between social isolation and mental health and emphasise the importance of recognising social isolation in children as a valuable indicator of co-occurring problems. Isolated children would benefit from support at the time they are isolated to reduce the risk of long-lasting problems. Where to go from here? Future efforts should be made to increase social support in young people and to better understand the bidirectionality of the link with mental health.

Links to previous blog posts:

L is for loneliness. https://blogs.kcl.ac.uk/editlab/2018/07/03/l-for-loneliness/

Read the full paper:

Thompson, K. N., Odgers, C. L., Bryan, B. T., Danese, A., Milne, B., Strange, L., Matthews, T., & Arseneault, L. (2022). Trajectories of childhood social isolation in a nationally representative cohort: Associations with antecedents and early adulthood outcomes. JCPP Advances, e12073. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcv2.12073

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank all the E-Risk Study mothers and fathers, children, children’s teachers and neighbours for their participation who have made a vital contribution to understanding development by sharing their experiences. Our thanks to Professors Terrie E. Moffitt and Avshalom Caspi, founders of the E‐Risk study and to the E‐Risk team for their dedication, hard work and insights.