“The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks” by Rebecca Skloot tells the story of the woman behind the first immortal human cell-line and that of her family. This book also highlights the research discoveries and important ethical issues ignited by the HeLa cells.

To be honest, I had not heard of Henrietta Lacks before reading this book. I understand, though, that she is a pretty famous lady (especially after the publication of this best-selling biography) and I feel a bit embarrassed to admit that I didn’t know this story, even more that while reading it I had to often remind myself that this is not fiction. That it is a true story.

“…this is mainly a story about scientific (mis)conduct and the importance of ethics in research.”

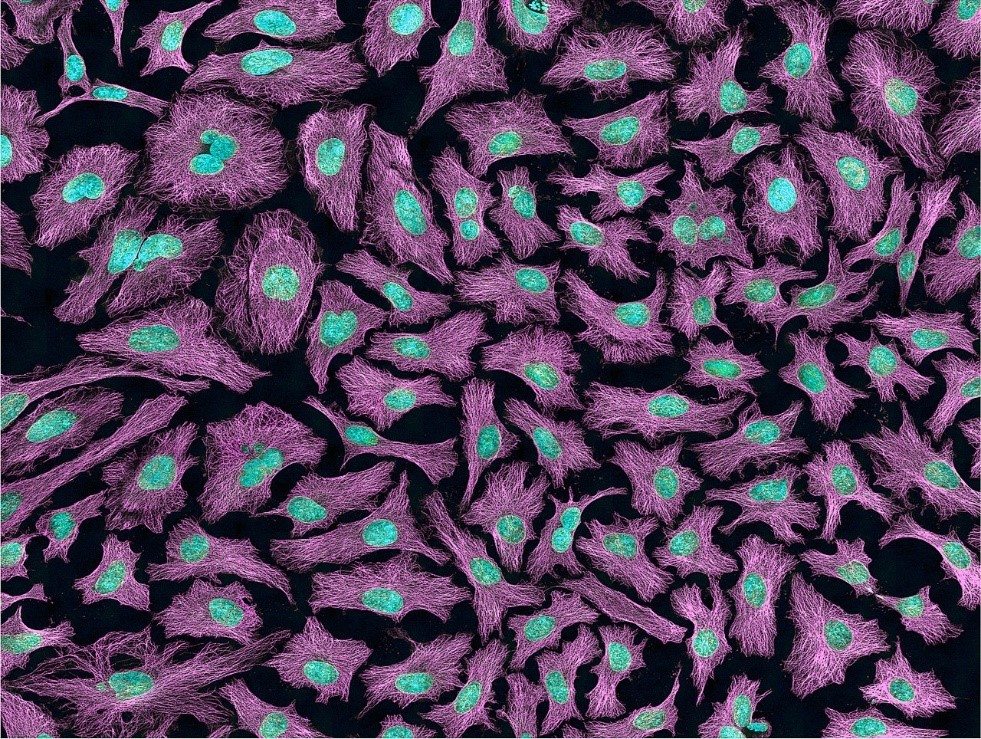

Henrietta Lacks was a poor, black woman, born and raised on a tobacco farm. At the age of 31 she died of cervical cancer and her cancer cells were taken without her consent. In an era when hospitals in the US had separate “coloured” sections, and when tales were circulating among black children about “night doctors” who would snatch them from the street to do weird experiments on them, a white doctor took a sample of Henrietta’s cancer cells and used them to produce the first ever line of human immortal cells (i.e. cells that do not die after a certain number of divisions). It is easy to focus on the racial and class elements of Henrietta’s story, but that would be a superficial reading of the story. This is not really about black and white people, or the exploitation of the poor and uneducated; this is mainly a story about scientific (mis)conduct and the importance of ethics in research.

The HeLa cells were cultured on a commercial scale and had been used in various types of groundbreaking research by hundreds of labs all over the world for about 20 years before Henrietta’s family found out. The doctors who took Henrietta’s cells without her or her family’s knowledge and consent did not do something out of the ordinary for their time. They just didn’t think that they needed to ask. Just like everyone else. Informed consent was not really a thing in the 50s and Henrietta was definitely not the only one. It wasn’t until the 60s, after a case of scientific misconduct (involving the injection of the cancerous HeLa cells into patients without their knowledge) ended up in court, that the National Institutes of Health (NIH) investigated their trustee institutions only to find that the vast majority of them did not have a policy for protecting the rights of research participants, and they did not use consent forms.

“…who owns human tissue that is not part of someone’s body anymore?”

Things have of course changed since then and the issue of informed consent and privacy of medical information is today very clearly laid out in laws and codes of ethics by various professional bodies. However, it took numerous formal legal procedures (and plenty of bad press) for researchers to take these issues into serious account. It is shocking to realise that at that time, most researchers saw nothing wrong with the way that things were done and many more thought that giving people the rights to their tissues would hinder research progress. Research was, without a doubt, important and valuable; it saved and still saves lives. But does the cause justify the means? Today it is very clear for us that the answer is no, but that was not always the case.

The existence of the HeLa cells created novel conditions and possibilities for scientific research. These brought about novel questions, such as: who owns human tissue that is not part of someone’s body anymore? Who has that right to the profits made out of human tissue: the person who donated the tissue, the researcher who grew it, or the research funding institution? Should people be informed about what research their tissue will be used for? The afterword of this book is an especially interesting read, as it includes the opinions of current (i.e. in 2009) researchers and stakeholders in biomedical research on questions surrounding privacy, informed consent, tissue ownership and commercialization.

“With the rapid advancement of science technologies, research communities will definitely be faced in the future with new challenges and situations currently not covered by existing codes of ethics.”

I think that stories like the one of Henrietta Lacks are important for researchers to be aware of. They showcase how far the field has come, and how we have (hopefully) learned from our mistakes along the way. They also emphasize the role of ethics in research and science curriculum. With the rapid advancement of science technologies, research communities will definitely be faced in the future with new challenges and situations currently not covered by existing codes of ethics. So, being attuned to ethical and moral aspects of our research, and being able to think ethically (and not just be aware of the existing rules), should be a core element in the training of future (and current) researchers. Ethics is not just a topic for abstract philosophical conversations over drinks. Ethics have practical instantiations in our research work, and the HeLa story is one of them.

PS. If all these feels too far away from home, check the Alder Hey scandal. Currently, human tissue handling in the UK is governed by the Human Tissue Act – making the storage and use of human tissue (including cells) without consent unlawful.

Further reading on informed consent:

Faden, R. R., & Beauchamp, T. L. (1986). A history and theory of informed consent. Oxford University Press.

Beauchamp, T. L. (2011). Informed consent: its history, meaning, and present challenges. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 20(4), 515-523.