Gender conventions and expectations have shaped the history of research into mental illness. Going forward we must be conscious of this influence – and encourage more males to participate in psychological research.

Recent posts on the blog from Thalia and Alicia emphasised the gender differences that exist in rates of suicide among young people in the UK. Of the total number of suicides registered here in 2014, 76% were males. Only half asked for help beforehand.

Alicia discussed the fact that females are more likely to receive support and treatment in times of need. She also highlighted that when males do seek help, suicide prevention strategies are not well tailored to account for gender differences in treatment response. But how have we got here, and how can we actually instigate change?

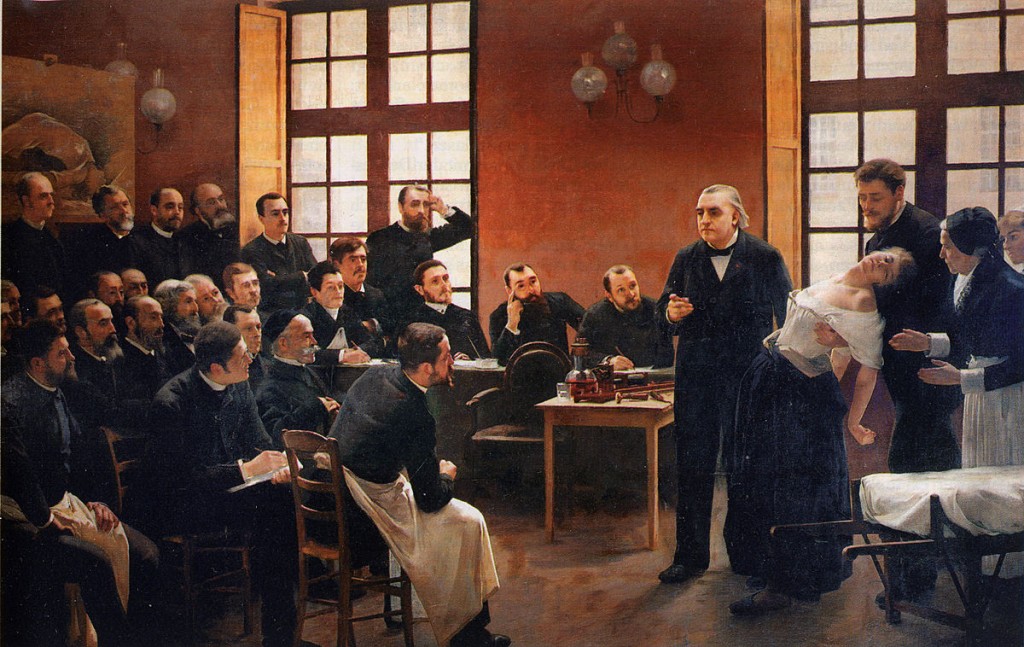

The history of research into mental illness has been underpinned by broader gender conventions and expectations. The painting below, titled A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière (1887), depicts the influential French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893) delivering a clinical lecture and demonstration at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris.

A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière, by Pierre Aristide André Brouillet (1857-1914)

Charcot was well known for his educational demonstrations, during which he would use hypnosis to take female models through the various stages of ‘hysteria’. Charcot believed that hysteria was underpinned by a weakened nervous system, triggered by a strong emotional response, characteristic of the female temperament. He produced an ‘iconography’ of hysteria (a picture book guide of symptoms), which was dominated by images of his female patients. A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière shows the woman as the focus of medical attention and scrutiny. It has become one of the best-known paintings in the history of medicine, with Sigmund Freud hanging a copy above his couch.

It wasn’t until World War I (1914 – 1918) that mainstream psychiatry really had to confront the fact that males can also suffer from mental illness. Soldiers began returning from the war with symptoms of ‘shell shock’ and clinicians were confused as to how these young men in their prime, supposedly the ‘fittest’ in society, could suffer from the same emotional symptoms that had been well-documented in women.

Psychiatry has evolved leaps and bounds since the turn of the 20th century – but the field is still not completely immune to the gender biases that continue to exist in society today. By and large, popular culture continues to deny male vulnerability, and males are all too frequently deprived of readily accessible emotional support as a result (again, see Alicia‘s post).

Marking a step in the right direction, two recent Academy Award-winning films – Moonlight and Manchester by the Sea – focused on depicting raw and uninhibited portrayals of male emotionality and mental illness (on another note, see Sarah‘s post for her take on on the moment when Moonlight won best picture). Around the same time, popular English grime and hip hop artist, Stormzy, opened up about his journey with depression (while his album Gang Signs And Prayer reached number 1 in the charts), and the soap-opera Eastenders (one of the most watched programmes on the BBC) was hailed for running a story-line in consultation with Samaritans to shine a light on male depression and suicide risk. Also in recent months, hundreds of footballers have spoken out about the sexual and psychological abuse that they were subject to as young players, and the lasting impact that these experiences had on their mental health.

However, as touched on in another previous post, the media (whether it be via the news, cinema, TV, or music) can’t be expected to carry the winds of change all on its own. Each of us is also responsible for making a conscious effort to be more open and receptive in our every day lives to male emotionality.

Such a shift in mainstream perception could also benefit research into psychiatric disorders – by encouraging more males to become research participants. Psychological research studies attract more female participants than they do males. It is therefore not always possible to investigate gender differences in the development and treatment of mental illness. This is also a problem for research focused on understanding the intergenerational transmission of mental illnesses – as to date most studies have focused solely on mother-child dyads, completely excluding fathers from the picture as they are harder to recruit to research in large numbers. This gender disparity is reminiscent of the problem that previously existed in clinical research – when females were excluded from participating in clinical trials (owing to fears for women’s health), resulting in the production of evidence based medicine that had never been tested on women.

We are about to launch a new study from the EDITlab called Children of TEDS (CoTEDS) – and we are hoping to recruit as many fathers as possible to take part. Hopefully the men that we approach will have all been watching this year’s Academy Award winning films, or listening to Stormzy, or keeping up-to-date with Eastenders or football – and as a result feel compelled to spare some time to support a research project focused on understanding the aetiology of common mental health disorders.

[…] is like for people close to those who are depressed. This article does something similar. This article picks up on the issue of male suicide, explaining that we know less about male than female mental […]