I have always been in admiration of cinema, believing it can be a powerful tool to convey a message to an audience who would otherwise have not been listening. For example, with films such as Erol Morris’ The Thin Blue Line, a criticism on the validity of eyewitness testimonies in court cases, I found myself more fascinated in the course I was studying than when sitting in a tedious, 2-hour lecture on forensic psychology.

Being so aware of its influence, though, means I have become more sensitive to movies that try and convey an ill-constructed message. Recently, this has been on the matter of mental illness and the way it is represented in the media. Between Lana Del Rey songs that romanticize depression, and “thinspiration” Instagram accounts glamorizing anorexia, the media is no stranger to distorting the truth behind a number of serious mental health issues. It therefore became a growing disappointment to gradually notice that the more I progressed in my understanding of mental health, the more I realized that cinema, arguably the most powerful mass media platform, has been dangerously idealizing mental illness. Instead of promoting its treatment, it pairs fragile mental health with protagonists who evoke a sense of mystery and allure. This is especially true with The Virgin Suicides.

The Virgin Suicides is told from the point of view of a group of men looking back, or even to some extent reminiscing, about a time when they were still young boys intrigued by the suicidal deaths of four sisters suffering from depression. The boys’ fixation on the Lisbon sisters begins because of their beauty, and they become gradually more engrossed when they discover the girls all seem to be hiding struggles with mental illness. They almost fetishize their depression, spying on them through their windows, explicitly saying other girls in school lack their allure and mystery. The cinematography loads onto this fetish, with the camera lingering on the girls as they laugh, lick their lips, and twirl their hair. These scenes then often cut to a more sombre image, such as a silent shot of the youngest sister bleeding in her bathtub after her first suicide attempt. All of this is done with a hazy, coloured filter meant to convey the reminiscence and embody the boys’ nostalgia.

Why this is a problem

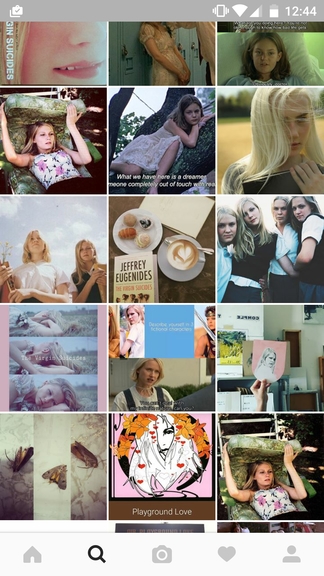

Its artistic shots, vintage 70s setting, and dead-beat adolescent suburbia plot have made this movie somewhat of a craze among young teenage girls. Instagram feeds and Tumblr dashboards are scattered with screen captures of the film, with the movie’s lines often used as captions for personal photos.

The Lisbon sisters have been interpreted as mysterious, complex and worthy of fixation, encouraging this idea that “being depressed and aloof is seductive.” This is extremely dangerous as it not only encourages harmful perceptions on mental health, but congruently allows others to assume that you can lie about your depression and adopt it as a trend. The movie therefore sacrificed an accurate portrayal of the dangers and damage of mental illness for the sake of intrigue and mystery, which means a step backwards for the representation of mental illness in the media.

[…] my last post, I highlighted a particularly glamorised portrayal of mental illness – that of the depression […]